Triggered on October 6, 1973 , the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, the a Yom Kippur War is the fourth war between Israel and neighboring Arab countries . Taking the initiative, the latter aim to recover the territories lost in 1967. It will take the Jewish state more than three weeks to repel its adversaries, at the cost of heavy losses. A regional showdown, this conflict will also have major global repercussions and will trigger the first oil shock that caused an economic crisis in the West. A high-intensity mechanized conflict, the Yom Kippur War was also a test bed for a whole series of materials and doctrines that still reign on the battlefields today.

Triggered on October 6, 1973 , the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, the a Yom Kippur War is the fourth war between Israel and neighboring Arab countries . Taking the initiative, the latter aim to recover the territories lost in 1967. It will take the Jewish state more than three weeks to repel its adversaries, at the cost of heavy losses. A regional showdown, this conflict will also have major global repercussions and will trigger the first oil shock that caused an economic crisis in the West. A high-intensity mechanized conflict, the Yom Kippur War was also a test bed for a whole series of materials and doctrines that still reign on the battlefields today.

The context of the Yom Kippur War

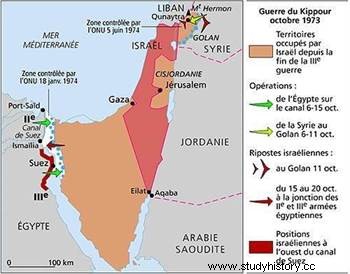

When the guns of the Six Day War fell silent on June 10, 1967, Israel appeared triumphant. Having defeated a pan-Arab coalition in less than a week, its armed forces are considered invincible. With the occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, Tel Aviv has acquired a protective glacis and borders that are much easier to defend. However, the Israeli leaders are not unaware that their main Arab adversaries (namely Egypt and Syria) refuse this state of affairs and intend to recover their territories with their heads held high. Thus the end of the 1960s saw the region sink into armed peace, a prelude to a new confrontation. On the Israeli side, this translates into the establishment of fortified positions, particularly on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal:the Bar Lev line.

Damascus and Cairo are also undertaking intense preparations for this new round of the long Arab-Israeli war. If the Israelis are abundantly equipped with Western equipment, the Soviet Union provides the equipment and the advisers necessary for the revival of the Arab armies. MIG 21 fighters, T 55 and T 62 tanks and above all thousands of anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles are delivered, on generous terms to Egyptians and Syrians. Nevertheless, the calculations of the different actors are ambivalent and sometimes contradictory.

If the Soviets maintained the preparation and the Arab war effort (Israelis and Egyptians then engaged in a war of low intensity attrition from 1967 to 1970), they did not wish however, not allow an open crisis to burst. Skeptical about the Arab powers' chances of success, they try to maintain a relative status quo, more favorable to maintaining their influence in the region. In Damascus, the team of Hafez El Assad , the Baathist and Alaouite dictator, we are determined to start a new war to recover the Golan. Cairo's motives are more complex.

Surprise Israel

Nasser's successor (died 1970), Awar Sadat was able to see the extent of the political crisis caused by the humiliating defeat of 1967. Aware of the country's economic difficulties and the relative failure of a whole section of Nasser's policies, Sadat knew that Egypt could collapse. He plans to ward off deep reforms, probably unpopular. Aware that a pro-Western alignment could be more beneficial in the long run than Nasser's flirtation with Moscow; the new Egyptian president conceives of a new war against Israel as a way of getting his country out of a difficult situation. It is not only a question of recovering Sinai, but also of providing it with the necessary legitimacy to carry out its major domestic and foreign policy projects.

Nasser's successor (died 1970), Awar Sadat was able to see the extent of the political crisis caused by the humiliating defeat of 1967. Aware of the country's economic difficulties and the relative failure of a whole section of Nasser's policies, Sadat knew that Egypt could collapse. He plans to ward off deep reforms, probably unpopular. Aware that a pro-Western alignment could be more beneficial in the long run than Nasser's flirtation with Moscow; the new Egyptian president conceives of a new war against Israel as a way of getting his country out of a difficult situation. It is not only a question of recovering Sinai, but also of providing it with the necessary legitimacy to carry out its major domestic and foreign policy projects.

For the two superpowers, the prospect of a new Arab-Israeli conflict is not a happy one. Both Nixon and Brezhnev feared serious economic repercussions, particularly on the price of oil (fears reinforced by OPEC's decision to drastically increase the price of a barrel in 1973). The unofficial but real nuclearization of Israel represents an additional cause for concern.

Thus in the summer of 1972, the Soviet Union and the United States made it known, by mutual agreement, that they supported a peaceful settlement of the conflict and the maintenance temporary status quo. In Cairo, where war is being intensively prepared, the reaction is immediate:the Soviet military advisers leave the country (they remain in Syria, however). During the following year the tension gradually increases as each of the belligerents refines their war plans. Both Moscow and Washington are proving powerless to defuse a crisis that has become inevitable.

It has often been written that the Egyptian and Syrian attack on October 6 came as a total surprise to Israel. In reality, even if it is triggered on a public holiday, the Tsahal staff has long planned an Arab offensive and the means to deal with it. However, we can only note the failure of the Israeli intelligence services to grasp the modalities and the timetable of the Arab offensive. Disoriented by the repeated maneuvers of the Egyptian and Syrian armies, the Israeli leadership is also the victim of a campaign of intoxication led by Cairo and Damascus.

It is thus assumed in Tel Aviv that the Arab powers are playing for time while waiting for the delivery of new Soviet equipment. The Egyptian army, deprived of its Soviet advisers, is considered to be weakened (in reality, it has gained in quality, in particular thanks to the purges of which we are paying the price, the incompetent generals of 1967). Plus Prime Minister Golda Meir refuses a new preventive attack, for fear of cutting itself off from the United States and the West. Result on this day of the great pardon of 1973, the Israeli army finds itself in a delicate situation, caught in a vice on two fronts.

Yom Kippur War:the Sinai front...

October 6, 1973 at two o'clock in the afternoon on this sacred day of the Judaic calendar, the Egyptian army, sure of its numerical superiority, launched the operation Badr . 200 fighter planes brutally hit IDF forces in the Suez Canal Zone and South Sinai. Far to the north, the Syrian army begins its assault on the Golan Heights. The Badr operation launched by the Syrian-Egyptians is the result of intense reflection on the failure of 1967. Convinced that the air force represented the greatest asset of the Israelis, the Egyptians set up a veritable anti-aircraft shield. -air using SAM missile battery, supposed to cover the troops that they will engage against the Bar-Lev line. To pierce the latter, Cairo aligns an assault genius, equipped with innovative equipment (including water cannons designed to destroy the sandy flats developed by the Israelis). Finally, anticipating an armored response from the Tsahal, the Egyptian army abundantly provided its units with 1 era line (which will remain without armored support for nearly 12 hours) of anti-tank missiles whose potential is neglected on the opposing side.

Result when the eastern bank of the Suez Canal Canal stormed on October 6, the Tsahal defense proved relatively ineffective. Deprived of the usual aviation support, faced with daring raids by helicopter commandos on their rear, the Israeli units can only retreat in the face of the 2

e

and 3

th

Egyptian armies. On the morning of October 7, nearly 850 Egyptian tanks had already crossed the Suez Canal. The forces of General Gonen (commander of the Sinai forces) and in particular the 162

th

armored division (led before the war by a certain Ariel Sharon ) must counterattack alone, with Tel Aviv giving priority to the Golan front.

Result when the eastern bank of the Suez Canal Canal stormed on October 6, the Tsahal defense proved relatively ineffective. Deprived of the usual aviation support, faced with daring raids by helicopter commandos on their rear, the Israeli units can only retreat in the face of the 2

e

and 3

th

Egyptian armies. On the morning of October 7, nearly 850 Egyptian tanks had already crossed the Suez Canal. The forces of General Gonen (commander of the Sinai forces) and in particular the 162

th

armored division (led before the war by a certain Ariel Sharon ) must counterattack alone, with Tel Aviv giving priority to the Golan front.

This counterattack turned out to be a complete failure, not only did the few Bar Lev line positions still held by the Tsahal remain isolated, but the 162 e division suffered heavy casualties. The Egyptian infantry, well aided by its anti-tank missiles, demonstrated a fighting spirit and a skill far superior to those of 1967. It proved it in the days that followed by sinking a little deeper into the Sinai, but at the cost of increasing losses.

The defeat suffered on the Bar-Lev line by the Israeli army has indeed caused a salutary shock in its ranks. Under the leadership of Chief of Staff Eleazar, the command is reshuffled with the recall of energetic officers like Sharon. On the other hand, the favorable evolution of the situation against the Syrians, allows Tsahal to release the reserves necessary for a counter-offensive. An operation made possible by the airlift that the United States then put in place (see below).

The Israelis recovered from their surprise, devise a plan to play their maneuvering superiority over an Egyptian army that has already paid dearly for its initial successes. Learning from the crucial importance of Egyptian anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles, they form infantry teams intended for their destruction. Combined arms cooperation tactics between infantry and armor are reviewed and improved.

On the 14th, at Sadat's insistence that he wanted to ease the pressure on the Syrians, the Egyptian army again attacked the IDF lines. The offensive, however carried out with large reinforcements of tanks, was a bitter failure. The botched plan having been reduced to a frontal shock on well-disposed Israeli positions, it resulted in terrible losses (more than 400 armored vehicles destroyed in a single day, 10 times less for the Israelis). The Tsahal's response is dazzling. Exploiting a breach between the 2 th and the 3 th Egyptian army, the 143 th Ariel Sharon's armored division (reservists, reinforced with parachute units) manages to seize a bridgehead on the African side of the canal (Operation Gazelle ). Meanwhile, two other Israeli armored divisions are working to cut off the Egyptians from their retreat routes. The anti-aircraft shield of the SAM missiles having partly neutralized, the Tel-Aviv aviation brings its full weight to bear in the battle.

It was only on the 17th that Sadat (using satellite photos provided by the Soviets who feared a total defeat of Egypt) understands that the 3

th

army risks being surrounded and wiped out in South Sinai. The Egyptian reaction, although slow and stiff (the officers having difficulty in freeing themselves from the original, very strict plan), is no less costly for the Israelis. Sharon is stopped near Ismailia by a light infantry force and struggles to regain the initiative.

It was only on the 17th that Sadat (using satellite photos provided by the Soviets who feared a total defeat of Egypt) understands that the 3

th

army risks being surrounded and wiped out in South Sinai. The Egyptian reaction, although slow and stiff (the officers having difficulty in freeing themselves from the original, very strict plan), is no less costly for the Israelis. Sharon is stopped near Ismailia by a light infantry force and struggles to regain the initiative.

This convinces Eleazar to opt for a slower tempo of operations, which will allow the Egyptians to commit their last armored reserves to the battle. So on the final Israeli advance, on the 23rd, they can just contain them. However, when the guns fell silent, the advanced Tsahal units were 100 km from Cairo and 70,000 Egyptian soldiers were cornered on the other side of the Suez Canal...

... and the Golan Front

On the Golan Heights, the Syrian army deploys an impressive force from October 6. Five divisions, supported by powerful artillery and air force against barely two Israeli brigades. However, several factors work against the Syrians. Firstly, the terrain on which they engage, uneven and compartmentalised, is much more favorable to the defensive. Second, if Israel is willing to cede space in the Sinai, it considers maintaining control of the Golan as a top priority. Indeed, if ever the Syrians were to seize it, they would be able to emerge into the plains overlooking large nearby cities:Haifa, Netanya and Tel Aviv. Thus in terms of sending reinforcements and reservists, the Golan front takes precedence over the Sinai.

For two days, the Syrians managed to obtain moderate success against the opposing forces, at the cost of heavy losses, especially in tanks. The two Tsahal brigades initially engaged, sacrifice themselves in order to allow the reservists to go up to the front (often transported by helicopters). Despite the capture of Mount Hermon, whose surveillance station is a crucial issue, the units of Damascus are unable to emerge from the heights of the plateau. On the 8th the Israelis can mount a counter-offensive with the help of three divisions (two of which are armored), on the 10th they reach the pre-war positions.

After a heated debate (Gonen's failures in the Sinai are on everyone's mind) the Israeli leadership decides to push its advantage against the Syrians. If this is a risky option on the military level, it is above all a political will, that of seizing adverse territories with a view to future talks (on this date, an Egyptian defeat in the Sinai is still a distant prospect). From 11 to 14 Tsahal continues its attack against the Syrians. The overwhelmed army of Damascus retreats precipitously and manages to stabilize the front line only at the cost of great sacrifices (and thanks to the help of foreign units, but we will come back to this). 10 days after the start of hostilities on the Golan, Israeli units reached 40 km from Damascus, a completely satisfactory result for Tel Aviv. If content with this, the Israelis will hardly carry out any offensive actions on this front (except the recapture of Mount Hermon) until the ceasefire.

An internationalized conflict

The Yom Kippur War immediately appeared as a conflict that went well beyond the Israeli-Syrian-Egyptian triangle. . On the one hand, it is an episode of the long Israeli-Arab confrontation and as such unleashes passions and initiatives in the Arab-Muslim world. Thus Damascus and Cairo can count on the financial and material support of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait (the equivalent of a brigade and large sums of money). Algeria is sending several air units to Egypt (as well as an armored brigade which will arrive on the front too late), as are Morocco and Libya. A brigade of Palestinians also participates in the conflict on the side of Sadat's army. Pakistan and Bangladesh are content with mainly medical aid. As for Jordanian and especially Iraqi aid (2 armored divisions), it enabled Syria to contain the Tsahal offensive in mid-October.

On the other hand, we cannot ignore the involvement of the two Cold War superpowers in the conflict. Although opposed to the decision of Sadat and Assad to go to war, the Soviets had no choice but to support them once the conflict started. From the 9th, Moscow undertook to resupply by sea (despite the brilliant successes of the Israeli navy which defeated the Syrians off Latakia on the 7th and the Egyptians at Damietta on the 8th and 9th) and by air to Syria and in to a lesser extent Egypt (sometimes via Libyan ports). Nearly 400 tanks were delivered to Damascus in three weeks as well as a large number of spare parts, ammunition, etc. Added to this is sometimes direct military aid from allies of the USSR, whether Cuba or North Korea.

Opposite, the American contribution to Israel's war effort is just as important. In the darkest hours of the conflict (and in particular on October 7, 8 and 9) Tel-Aviv skillfully put pressure on Washington by ostensibly activating the plan providing for the use of nuclear weapons. This is to convince President Nixon (moreover weakened by the Watergate affair and under the influence of Henry Kissinger ) of the seriousness of the situation.

Opposite, the American contribution to Israel's war effort is just as important. In the darkest hours of the conflict (and in particular on October 7, 8 and 9) Tel-Aviv skillfully put pressure on Washington by ostensibly activating the plan providing for the use of nuclear weapons. This is to convince President Nixon (moreover weakened by the Watergate affair and under the influence of Henry Kissinger ) of the seriousness of the situation.

The United States, which fears above all a nuclearization of the conflict, agrees to provide substantial aid to Israel to compensate for its losses in the first days. A gigantic airlift is set up (Operation Nickel Grass ) supplemented by naval aid. The thousands of tons thus delivered allow the Tsahal to supply offensives, while replenishing reserves of equipment.

While the Soviets and Americans provide the armies of their respective clients and allies, they nevertheless share the common conviction that this conflict risks dragging them to extremes that they try at all costs to avoid. It is therefore with their unconditional support that a united nations resolution (resolution 388) enjoined, on October 22, the belligerents to cease the fight . When it appears that the Israelis are neglecting it in order to push their advantage in Egypt, the Soviets do not hesitate to put their armed forces on nuclear alert, plunging the American national security council into panic.

The American pressure which then fell on Israel was sufficient to make Tel Aviv accept the terms of a ceasefire on October 25 . After a few adventures, it comes into force on October 28. The well-understood interests of the super bigs finally prevailed over Middle Eastern issues.

Lessons and consequences of the Yom Kippur War

Barely One Month War, the 4 th Arab-Israeli war, constitutes one of the most intense mechanized conflicts post-World War II. The material losses are impressive and reveal the power of modern armaments. Nearly 2,500 tanks destroyed (including 80% on the Syrian-Egyptian side), more than 400 planes shot down (including a hundred Israelis). On the human level, the losses amounted to 30,000 men on the Arab side (about 10,000 dead), 11,000 on the Israeli side (about 3,000 dead). The fighting rehabilitated the role of infantry in combined arms tactics and cooperation with armour. They also proved the importance of anti-tank and anti-aircraft means s, relativizing the role of the tank-aircraft binomial. Finally, they gave pride of place to special forces and intelligence services, whose role has continued to grow ever since.

On the Arab and especially Egyptian side, the fact of having put Israel in difficulty more than at any time since 1948 was considered (and especially by propaganda) as a victory. Defeated militarily, Sadat has nonetheless won his bet and legitimized his power with the Egyptians (with the notable exception of the Islamists, who will be fatal to him...). Egypt has once again become the flagship nation of the Arab world and has free rein tonegotiate against an Israel in full doubt.

On the Arab and especially Egyptian side, the fact of having put Israel in difficulty more than at any time since 1948 was considered (and especially by propaganda) as a victory. Defeated militarily, Sadat has nonetheless won his bet and legitimized his power with the Egyptians (with the notable exception of the Islamists, who will be fatal to him...). Egypt has once again become the flagship nation of the Arab world and has free rein tonegotiate against an Israel in full doubt.

Indeed for the Hebrew state, the Yom Kippur War was a bitter disappointment. The myth of the invincibility of the Tsahal has been severely undermined, as has that of the infallibility of the intelligence services. The ensuing political crisis cost Labor their dominance, which eventually gave way to Likud , a young right-wing party, in 1977. Added to this is a deep moral questioning of the Israeli nation, where the secular Zionism of the beginnings is gradually giving way to the influence of the religious. Disoriented Israel, has also seen itself isolated internationally, its relationship with Washington disrupted by events.

This tends to explain why the Israeli-Egyptian dispute was settled so quickly. Sadat, building on his success in 1973, took the initiative in direct negotiations with the Likud government of Menahen Begin in 1977. For Cairo, as for Tel Aviv, this was an opportunity to put an end to a costly conflict and to make a gesture towards Washington. Two years later with the Camp David agreements, Israelis and Egyptians definitively embarked on the road to peace, reflected in the gradual retrocession of Sinai to Egypt.

Sadat's triumph, however, will be short-lived. Criticized by his former allies (and in particular Syria which persists in its opposition to Washington), the Egyptian president will see his country excluded from the Arab League. He was assassinated on October 6, 1981, the anniversary of the start of Operation Badr, by Islamist soldiers revolted by his pro-American turnaround and by peace with Israel.

Bibliography

- The Yom Kippur War of October 1973, by Pierre Razoux. Economica, 1999.

- The Yom Kippur War Will Not Happen:How Israel Was Caught By Frédérique Schillo. André Versaille Edition, 2013.

- The Yom Kippur War:The Arab-Israeli conflict that caused the first oil shock. 50 Minutes, 2014.