Largest country in South America, Brazil is beyond the clichés a country rich in history strongly influenced by Portuguese colonization. Pedro Álvares Cabral took possession of it in the name of the King of Portugal in 1500 and the colony quickly became prosperous, attracting the covetousness of the French and the Dutch. Brazil gained independence in 1822, moving from the status of empire to that of a republic in 1889. With significant natural resources, Brazil experienced strong economic growth in the previous century as well as an increase in social inequalities. The organization of the Olympic Games in 2016 was to consecrate the emergence of this country on the world stage, tarnished since by a serious political and environmental crisis.

Largest country in South America, Brazil is beyond the clichés a country rich in history strongly influenced by Portuguese colonization. Pedro Álvares Cabral took possession of it in the name of the King of Portugal in 1500 and the colony quickly became prosperous, attracting the covetousness of the French and the Dutch. Brazil gained independence in 1822, moving from the status of empire to that of a republic in 1889. With significant natural resources, Brazil experienced strong economic growth in the previous century as well as an increase in social inequalities. The organization of the Olympic Games in 2016 was to consecrate the emergence of this country on the world stage, tarnished since by a serious political and environmental crisis.

History of Brazil, Portuguese colony

Spanish navigator Pinzón was the first European explorer to reach Brazil. After his transatlantic crossing, he made landfall near the site of present-day Recife on January 26, 1500. However, under the decisions of the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which modified the dividing line established in 1493 by Pope Alexander VI to delimit the Portuguese and Spanish empires, the new territory was assigned to Portugal.

Spanish navigator Pinzón was the first European explorer to reach Brazil. After his transatlantic crossing, he made landfall near the site of present-day Recife on January 26, 1500. However, under the decisions of the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which modified the dividing line established in 1493 by Pope Alexander VI to delimit the Portuguese and Spanish empires, the new territory was assigned to Portugal.

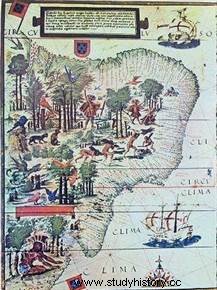

In April 1500, the Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral also reached the Brazilian coast. He officially proclaimed the region possession of Portugal. The territory was named Terra da Vera Cruz (in Portuguese, “Land of the True Cross”). In 1501, the Italian navigator Amerigo Vespucci led an expedition to this new territory at the instigation of the Portuguese government. During his explorations, Vespucci recognized and named many capes and bays, including that of Rio de Janeiro. He returned to Portugal with brazil (wood from Pernambuco which provides a red dye). The Terra da Vera Cruz took, from this date, the name of Brazil.

In 1530, the king of Portugal, John III the Pious, began a program of systematic colonization of Brazil. Resorting to slavery, the Portuguese based their wealth on the cultivation of sugar cane and the extraction of gold and diamonds. France, interested in this new territory, tried to seize it. Frequent French incursions and the threat they posed to this possession of the Portuguese Crown eventually prompted King John to place Brazil under the authority of a Governor General.

The first, Thomé de Souza, arrived in Brazil in 1549, set up a central government whose capital was established in the new city of Salvador de Bahia. He completely reformed the administration and justice. To protect the country from the French threat, he established a coastal defense system. The importation of many African slaves made it possible to compensate for the shortage of local labour. It was during this period, in 1554 exactly, that the city of São Paulo was founded in the south of the country.

An object of desire

The following year, in 1555, the French, under the leadership of Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon attempted to settle by establishing a colony on the shores of the bay of Rio de Janeiro. In 1560, the Portuguese destroyed this colony and created, in 1567, the city of Rio de Janeiro. The French expelled, Brazil will still have to resist frequent English and Dutch aggression until the middle of the 17th century.

In 1580, Philip II, King of Spain, inherited the crown of Portugal. This period of union of the two kingdoms, until 1640, was marked by frequent English and Dutch aggression against Brazil. Thus, in 1624, a Dutch fleet seized Bahia. But the following year, the city was taken over by an army made up of Spaniards, Portuguese and Indians. The Dutch resumed their attacks in 1630. On this occasion, an expedition subsidized by the Dutch West India Company took Pernambuco, present-day Recife, and Olinda.

The territories between the island of Maranhão and the area downstream of the São Francisco thus fell into Dutch hands. Under the competent authority of Jean-Maurice de Nassau-Siegen, the part of Brazil occupied by the Dutch prospered for several years. But in 1644, Nassau-Siegen resigned to protest against the exploitation carried out by the Dutch West India Company. Shortly after his departure, the Portuguese colonists, supported by Portugal, which became independent from Spain again in 1640, rebelled against the Dutch power. In 1654, after ten years of struggle, the Netherlands capitulated and, in 1661, they officially renounced their territorial claims on Brazil.

Portuguese expansion in Brazil nevertheless continued inland, led among others by Jesuit missionaries, who advanced into the Amazon and established missions there. Under the reign of King Joseph I of Portugal, Brazil experienced many reforms at the instigation of the Marquis of Pombal, Secretary for Foreign Affairs and War then Prime Minister. Indian slaves were freed, immigration encouraged and taxes reduced. Pombal reduced the weight of the royal monopoly on the international trade of the viceroyalty, centralized the Brazilian government apparatus whose seat was transferred from Bahia to Rio de Janeiro in 1763. Three years earlier, in 1760, following the example of this which he had already done in 1759 in Portugal, Pombal expelled the Jesuits from Brazil. The official reason was the popular discontent aroused by the Jesuit influence among the Indians and their growing weight in the economy.

Towards the independence of Brazil

The Napoleonic wars profoundly changed the course of Brazilian history. In 1807, Napoleon invaded the Iberian Peninsula, forcing the Portuguese monarchy to settle in Brazil. Reforms were implemented, including the removal of trade restrictions, the introduction of measures in favor of agriculture and industry, and the creation of higher education institutions. Nevertheless, corruption and incompetence affected the royal government, which quickly lost credibility with a population won over by the ideas of the French Revolution.

In 1822, the regent of Portugal Dom Pedro broke with the metropolis by convening a constituent assembly and proclaiming the independence of Brazil, of which he became emperor under the name of Peter I. Brazil was then subject to the authority of a regime marked by frequent uprisings and revolts in the provinces. Towards the end of this decade a popular movement developed in favor of the young Peter II, intended to put him effectively at the head of the government.

In 1822, the regent of Portugal Dom Pedro broke with the metropolis by convening a constituent assembly and proclaiming the independence of Brazil, of which he became emperor under the name of Peter I. Brazil was then subject to the authority of a regime marked by frequent uprisings and revolts in the provinces. Towards the end of this decade a popular movement developed in favor of the young Peter II, intended to put him effectively at the head of the government.

Peter He proved to be one of the most able monarchs of his time. Under his reign, which lasted nearly half a century, the economic and demographic growth of the country was exceptional. National production was multiplied by ten and the country began to build a rail network. Peter II, however, had to face the hostility of part of the clergy towards his policy as well as the hidden infidelity of many officers and the rise of republican sentiment in public opinion.

Brazil, between growth and coups

Brazil became a federal state with the revolution of 1888, provoked by the hostility of large landowners to Emperor Peter II's decision to abolish slavery. Long controlled by this oligarchy of "Corronels", whose coffee culture ensured the power, the country was affected by the economic crisis of the 1930s, which favored the election of Getulio Vargas.

Vargas initially undertook numerous reforms, including women's suffrage, social security for workers, and the election of the president by Congress, before relenting authoritarian temptation, establishing a regime strongly inspired by fascism, the Estado Novo. Political parties were banned, the press and correspondence were subjected to strict censorship. During World War II, Brazil nevertheless sided with the allies. Its contribution to the conflict was above all economic:a vast program of industrial expansion made it possible to increase the production of rubber and other vital war material.

After World War II, Brazil experienced a long period of political instability, punctuated by military military state. The modernist policy of President De Oliveria (1956-1960) allowed the development of the interior of the country around a new capital, Brasilia. The agrarian reform projects of his successor, President Goulart, aroused the opposition of the army, which seized power, establishing a state of exception in 1964. The inability of successive military regimes to halt the deterioration of the he economy provoked the return to civilian rule, with the election of President José Sarney in 1985, whose fight against inflation was, however, a failure.

After World War II, Brazil experienced a long period of political instability, punctuated by military military state. The modernist policy of President De Oliveria (1956-1960) allowed the development of the interior of the country around a new capital, Brasilia. The agrarian reform projects of his successor, President Goulart, aroused the opposition of the army, which seized power, establishing a state of exception in 1964. The inability of successive military regimes to halt the deterioration of the he economy provoked the return to civilian rule, with the election of President José Sarney in 1985, whose fight against inflation was, however, a failure.

The dismissal in 1992 for corruption of his successor, Fernando Collor de Mello, owner of the main Brazilian television channel, replaced by Itamar Franco then by Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1994), and the vote in favor of the republican system in the 1993 referendum prove the political maturity of a country still confronted with the weight of its foreign debt and the permanence of social inequalities.

From Lulla to Bolsonaro

It was in this context that the first socialist president of Brazil, Lula da Silva, an emblematic figure of the Brazilian trade union left, was brought to power in 2002. His victory arouses great hopes for change among the population. Forced to pursue a policy of economic stability in order to satisfy financial circles, while striving to meet the social expectations of the population, Lula proposed a "social pact" aimed at bringing together all the players in society and achieving a consensus on the reforms to be carried out, in particular tax reform and agrarian reform.

Dilma Rousseff, who succeeded Lulla, faces an explosion of crime and suspicions of corruption. His dismissal in 2016 after a controversial procedure paves the way for the election in 2018 of Jair Bolsonaro, a populist classified on the far right and nostalgic for the military dictatorship...

Bibliography

- History of Brazil, 1500-2000 by Bartolomé Bennassar. Fayard, 2000.

- Brazil:History, society, culture of Lamia Oualalou. The Discovery, 2009.