The May 30, 1862 occupation of Corinth, evacuated the day before by the Confederates, left the Union in an advantageous strategic position. If Beauregard's 56,000-strong southern army blocked the Federals' direct southern route by entrenching themselves in Tupelo, other options remained open thanks to the railroads that radiated from Corinth. Having become indefensible, Western Tennessee and the city of Memphis were just waiting to fall like ripe fruit – the second, moreover, was occupied on June 6 by Northern gunboats, once the Confederate river flotilla was destroyed.

The May 30, 1862 occupation of Corinth, evacuated the day before by the Confederates, left the Union in an advantageous strategic position. If Beauregard's 56,000-strong southern army blocked the Federals' direct southern route by entrenching themselves in Tupelo, other options remained open thanks to the railroads that radiated from Corinth. Having become indefensible, Western Tennessee and the city of Memphis were just waiting to fall like ripe fruit – the second, moreover, was occupied on June 6 by Northern gunboats, once the Confederate river flotilla was destroyed.

Strategic spread

This success opened the road north to Vicksburg, the last Confederate bastion on the Mississippi, already besieged by David Farragut's fleet. In the opposite direction, the middle reaches of the Tennessee and the railroad that ran along it could lead to Chattanooga, the gateway to Eastern Tennessee . This was a tempting target for President Lincoln, ever concerned about the fate of Union sympathizers in the region.

Henry Halleck, who commanded the combined armies of Pope, Grant and Buell, had a vast numerical superiority over Beauregard, with a force close to double that fielded by the Southerners . The passivity of his adversary had also somewhat reassured Halleck, initially worried by the aggressiveness deployed by the Confederates at the time of the Battle of Shiloh. Beauregard, moreover, left the initiative to the Federals during the month of June. His retreats from Shiloh and Corinth had not helped his relations, already extremely strained since the controversy that opposed them in the fall, with President Davis. In addition, the Cajun had suffered for several months from fragile health, which affected his already little offensive temperament. When Beauregard went on leave to take care of himself without consulting Davis, the latter relieved him of his duties on 17 June. The southern president replaced him with one of his subordinates, Braxton Bragg . The latter, who had commanded one of the wings of the southern army in Shiloh, had for him to get along very well with Davis, which was not given to everyone given the difficult nature - and aggravated by many painful nerves – from the President of the Confederation.

Northern command also underwent significant changes, but for diametrically opposed reasons. Recognizing Halleck as the organizer and staff officer he needed to plan his overall strategy, Lincoln called him back to Washington, where he took over as commanding general of the army on July 23—thus ending his tenure. a vacancy of more than four months and on an interim basis provided by the War Board . Lincoln also brought his protege John Pope to the eastern theater of operations, to place him in command of the newly formed Army of Virginia. These promotions left as main officers in the West the controversial Ulysses Grant, still followed by his sulphurous reputation as an alcoholic, and Don Carlos Buell , considered by many to be the victor of Shiloh thanks to the timely arrival of his army on the second day of the battle. Both Halleck and Lincoln recognized the paramount importance of Vicksburg in carrying out the "Anaconda Plan" and controlling the Mississippi, but neither understood what Farragut had immediately realized on arriving in front of the city with his fleet:the cliffs of Vicksburg made it impregnable by a naval action only.

The northern command even persuaded itself otherwise. He made no arrangements to send to Farragut, joined during the summer by Commodore Charles H. Davis' river flotilla, the infantry which was sorely needed to storm the Confederate batteries installed on the heights of Vicksburg. Instead, Lincoln once again gave in to the sirens—and political imperatives—of East Tennessee. It was his third attempt in this direction since the beginning of the war. Buell's timid attacks in the winter of 1862 had been deflected by the fall of Nashville, the conquest of central Tennessee, and the offensive against Corinth. The action envisaged in the spring by Frémont, who intended to invade East Tennessee from West Virginia, had been quickly thwarted by the actions of Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, and then abandoned. Lincoln therefore decided that the main summer offensive in the West would be aimed at Chattanooga . The capture of the latter would indeed open up the Upper Tennessee Valley to the Northerners, the only major axis of communication in this very mountainous region.

The northern command even persuaded itself otherwise. He made no arrangements to send to Farragut, joined during the summer by Commodore Charles H. Davis' river flotilla, the infantry which was sorely needed to storm the Confederate batteries installed on the heights of Vicksburg. Instead, Lincoln once again gave in to the sirens—and political imperatives—of East Tennessee. It was his third attempt in this direction since the beginning of the war. Buell's timid attacks in the winter of 1862 had been deflected by the fall of Nashville, the conquest of central Tennessee, and the offensive against Corinth. The action envisaged in the spring by Frémont, who intended to invade East Tennessee from West Virginia, had been quickly thwarted by the actions of Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, and then abandoned. Lincoln therefore decided that the main summer offensive in the West would be aimed at Chattanooga . The capture of the latter would indeed open up the Upper Tennessee Valley to the Northerners, the only major axis of communication in this very mountainous region.

This strategic choice was accompanied by a major reorganization. The Mississippi Military Department was disbanded, leaving the federal armies in the West without a unified command. A unique structure was put in place:while keeping the head of the Army of Tennessee, Grant was entrusted with a "district of Western Tennessee" which also included the Army of Mississippi, now commanded by William Rosecrans instead of Pope. Buell, on the other hand, regained full autonomy at the head of the army of Ohio, which would allow him to lead the offensive against Chattanooga. He initially had about 30,000 men to do this, while Grant kept 80,000 under his command. However, it soon became apparent that the forces entrusted to Buell were insufficient. The Union forces were faced with a new problem:occupying hostile territory, they had to leave behind large detachments to ensure the security of their communications . The Mississippi Army was relieved of three-quarters of its strength to reinforce Buell's, while one of Grant's divisions was sent to Arkansas to occupy Helena. Within weeks, Grant had only 50,000 men left, the majority of whom were dispersed to defend several railroad junctions. This situation drove him to the defensive, and the northern general was not going to undertake any offensive action during the summer.

Guerrilla and cavalry raids

Buell enjoyed a virtually invulnerable supply axis with the Tennessee River; unfortunately for him, it was not navigable to Chattanooga. This situation left him dependent on the Memphis &Charleston Railroad , the railroad line that led directly from Corinth to Chattanooga. The Northerners soon found that cutting this railway line was child's play for their enemies . Groups of Confederate resistance fighters from Tennessee and Alabama, most often mounted civilians, were formed during a raid into units of "partisan rangers" who targeted the least protected bridges or stations to set them on fire. In a few hours, these guerrillas could dismantle an unprotected section of railway, pile the rails on the sleepers and set them on fire:the heat deformed the iron of the rails, which was enough to make them unusable. It then took several days for the northern engineers to restore the rail link. The southern partisans also increased their ambushes against isolated detachments or supply vans, before dispersing again to take refuge in their farms. One of Buell's subordinates, General Robert L. McCook, was killed in such a skirmish on August 6.

Buell enjoyed a virtually invulnerable supply axis with the Tennessee River; unfortunately for him, it was not navigable to Chattanooga. This situation left him dependent on the Memphis &Charleston Railroad , the railroad line that led directly from Corinth to Chattanooga. The Northerners soon found that cutting this railway line was child's play for their enemies . Groups of Confederate resistance fighters from Tennessee and Alabama, most often mounted civilians, were formed during a raid into units of "partisan rangers" who targeted the least protected bridges or stations to set them on fire. In a few hours, these guerrillas could dismantle an unprotected section of railway, pile the rails on the sleepers and set them on fire:the heat deformed the iron of the rails, which was enough to make them unusable. It then took several days for the northern engineers to restore the rail link. The southern partisans also increased their ambushes against isolated detachments or supply vans, before dispersing again to take refuge in their farms. One of Buell's subordinates, General Robert L. McCook, was killed in such a skirmish on August 6.

The Confederates had initially decided to go all out on the harassment card. Edmund Kirby Smith, who was in charge of the defense of East Tennessee (and enjoyed, like Buell, autonomy of command vis-à-vis Bragg) dispersed his forces to weigh on the supply axes of Buell a diffuse but permanent threat. It was not long, however, to revise its strategy. From the beginning of June, a detached division of the Army of Ohio, commanded by James Negley, launched a reconnaissance in force from Nashville in the direction of Chattanooga. Advancing rapidly, Negley engaged in an artillery duel for two days, June 7 and 8, which informed him of the weak defenses of Chattanooga. The northern general, however, was in an isolated position and did not want to risk being cut off from his rear. He backed off to Murfreesboro, but the case served as a warning to E.K. Smith. Aware that the loss of Chattanooga would render the deployment of his forces obsolete, he had the bulk of his forces concentrated there, a little over 20,000 soldiers. This movement led to the abandonment, by the Confederates, of the Cumberland Lock , strongly fortified, and which commanded the main access to East Tennessee from the north. Federal troops moved there on June 18.

These initial successes did little to help Buell, however, as his eastward advance was at a snail-like. The occupation of Decatur, then of Huntsville, in northern Alabama, enabled him to shorten his supply lines by opening a new railway axis which linked him directly to Nashville. A few more miles, and the Nashville &Chattanooga Railroad would open a second one via Tullahoma and Murfreesboro. But far from relieving Buell, this new situation forced him to disperse even further. By early August, the Ohio Army, even reinforced, was stretched across northern Alabama, from Florence to Huntsville, not counting the garrisons posted across central Tennessee. At the same time, the Confederacy had begun to experiment with another strategy. Recovered from the serious wound received at Shiloh, Nathan Bedford Forrest was promoted brigadier-general and was entrusted with a brigade of cavalry, 1,400 strong in all. At the same time, Colonel John Hunt Morgan, a native of Kentucky, assembled a similar force of 900 cavalry, consisting mainly of pro-Southern Kentuckians. The two columns were ordered to both launch a deep raid in the territory occupied by the Northerners, each in their respective States:Forrest in Tennessee, Morgan in the direction of Kentucky. The first left Chattanooga on July 9, while Morgan had left Knoxville five days earlier.

These initial successes did little to help Buell, however, as his eastward advance was at a snail-like. The occupation of Decatur, then of Huntsville, in northern Alabama, enabled him to shorten his supply lines by opening a new railway axis which linked him directly to Nashville. A few more miles, and the Nashville &Chattanooga Railroad would open a second one via Tullahoma and Murfreesboro. But far from relieving Buell, this new situation forced him to disperse even further. By early August, the Ohio Army, even reinforced, was stretched across northern Alabama, from Florence to Huntsville, not counting the garrisons posted across central Tennessee. At the same time, the Confederacy had begun to experiment with another strategy. Recovered from the serious wound received at Shiloh, Nathan Bedford Forrest was promoted brigadier-general and was entrusted with a brigade of cavalry, 1,400 strong in all. At the same time, Colonel John Hunt Morgan, a native of Kentucky, assembled a similar force of 900 cavalry, consisting mainly of pro-Southern Kentuckians. The two columns were ordered to both launch a deep raid in the territory occupied by the Northerners, each in their respective States:Forrest in Tennessee, Morgan in the direction of Kentucky. The first left Chattanooga on July 9, while Morgan had left Knoxville five days earlier.

On July 13, Forrest surrounded the small northern garrison at Murfreesboro, commanded by Thomas T. Crittenden, a nephew of Kentucky Senator John Crittenden. Arrived the day before, taken by surprise, the northern general was captured with almost all of his 900 men. The destruction of the Murfreesboro Railroad Depot allowed Forrest to cut the Nashville &Chattanooga Railroad , closing Buell the possibility of using it. Morgan, for his part, drove deep into the heart of Kentucky, taking a total of 1,200 prisoners by seizing the Northern depots at Tompkinsville (July 9) and Cynthiana (July 14). Morgan's raid, even more spectacular than Forrest's, also allowed the southern command to draw rich lessons on several levels. Morgan and his men had been very well received by the local population, especially around Lexington, where sympathies for the secessionist cause were relatively strong. Several hundred volunteers joined the Southern column, so much so that Morgan ended the operation with more soldiers than he had begun. This result convinced Davis that it would be enough to invade the state for Kentucky to rise en masse and side with the Confederates , and the Southern President ordered Bragg to stage this invasion.

Confederation covets Kentucky

On July 31, 1862, Bragg and Kirby Smith met in Chattanooga to decide on a common strategy . Bragg proposed to transfer his base to Chattanooga with the bulk of his army, 35,000 men, the rest remaining in Tupelo under the command of Earl Van Dorn. At the same time, Smith was to march north with his own army to retake the Cumberland Sluice, and eliminate the threat posed by the 10,000 Union soldiers stationed there. Once done, Smith would turn around to join Bragg. The two combined armies would then march on Nashville, hoping to force Buell to abandon his plans and fight a decisive battle from an unfavorable position. At the same time, Van Dorn would launch diversionary attacks against the positions held by Grant, in order to prevent him from reinforcing Buell. Only after the Army of Ohio was destroyed, or at least badly defeated, would the Confederates march north to invade, or from their perspective liberate, Kentucky.

On July 31, 1862, Bragg and Kirby Smith met in Chattanooga to decide on a common strategy . Bragg proposed to transfer his base to Chattanooga with the bulk of his army, 35,000 men, the rest remaining in Tupelo under the command of Earl Van Dorn. At the same time, Smith was to march north with his own army to retake the Cumberland Sluice, and eliminate the threat posed by the 10,000 Union soldiers stationed there. Once done, Smith would turn around to join Bragg. The two combined armies would then march on Nashville, hoping to force Buell to abandon his plans and fight a decisive battle from an unfavorable position. At the same time, Van Dorn would launch diversionary attacks against the positions held by Grant, in order to prevent him from reinforcing Buell. Only after the Army of Ohio was destroyed, or at least badly defeated, would the Confederates march north to invade, or from their perspective liberate, Kentucky.

The execution of this complex plan, which required great coordination between the various armies involved, was based on a gentlemen’s agreement between Bragg and Smith. It was agreed between the two men that Smith, despite the autonomous nature of his command, would become subordinate to Bragg once their two armies were united. However, Smith was particularly jealous of his independence, and had his own ambitions. Davis could have greatly simplified the problem by placing him explicitly under Bragg's command, but he did not . When Smith began his offensive from Knoxville on August 13, he was in no rush to overcome the Cumberland Sluis. Rather than attacking him directly, he soon convinced himself that it was better to maneuver to force the Northerners to evacuate him. Incidentally, this move would lead him to enter Kentucky without further ado, allowing Smith to take credit for the victory on his own. Dividing his forces, the southern general instructed Carter Stevenson to fix the northern defenses while he himself would take a secondary road to lead to their rear. On August 18, Smith got his way. The Federal garrison was not completely encircled, but it had to abandon the Cumberland Sluice and retreat eastward, sinking into the mountains and finding itself out of action for the rest of the campaign.

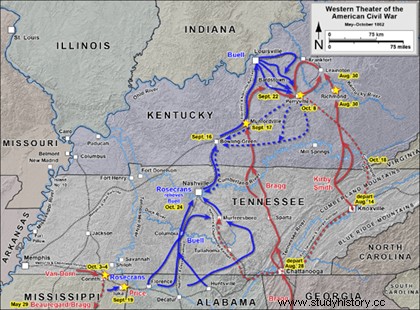

Overview of operations in the West between July and November 1862. Map by Hal Jespersen (www.cwmaps.org).

Overview of operations in the West between July and November 1862. Map by Hal Jespersen (www.cwmaps.org).

Smith made no secret of his intentions from Bragg, forcing the latter to completely alter his plans . Confirming to Van Dorn that he was still to carry out the initially planned diversionary attacks, and if necessary come to join him, he left Chattanooga on August 27. Instead of marching on Nashville, Bragg headed straight north, through a rough road through Appalachia. His goal now was to join Smith in Lexington. Despite its improvised nature, the Confederate offensive caused panic in the Union ranks. Buell's army was far to the south, and his opponents were between him and Louisville, the Union's main rear base in the west. All available troops, including thousands of freshly drafted, ill-equipped, and untrained volunteers, were rushed to Kentucky. General Horatio Wright was assigned to lead this massive effort, and Buell sent his subordinate William Nelson to him to coordinate the troops in the field. These, newly organized into a “Provisional Army of Kentucky,” began to concentrate in Richmond, in the eastern part of the state.

They were however taken aback by the advanced elements of Smith's army:7,000 men under Patrick's orders Cleburne, placed temporarily at the head of the troops that Bragg had "lent" to Smith. Nelson had not yet arrived in Richmond, and the 6,500 Northerners there were commanded in his absence by Mahlon Manson. On the morning of August 29, horsemen from both sides met south of Richmond. The skirmish escalated, and the reinforced Federals took the lead during the afternoon. Encouraged by this success, Manson pushed his own brigade forward, despite Nelson's formal orders not to engage his still "blue" recruits. Night fell before the fight got too serious, but it gave Cleburne the opportunity to regroup. At dawn on the 30th, the Southerners attacked, immediately forcing Manson to fall back. Despite the arrival of reinforcements, and then of Nelson himself, the Federals eventually cracked, and the retreat of their inexperienced troops turned into a debacle . Over 4,000 Unionists, including Manson himself, were captured, Nelson was shot in the thigh, and the "Provisional Army of Kentucky" was virtually destroyed. Confederate losses amounted to less than a tenth of those of their enemies. They did, however, include Cleburne, injured superficially in the face.

They were however taken aback by the advanced elements of Smith's army:7,000 men under Patrick's orders Cleburne, placed temporarily at the head of the troops that Bragg had "lent" to Smith. Nelson had not yet arrived in Richmond, and the 6,500 Northerners there were commanded in his absence by Mahlon Manson. On the morning of August 29, horsemen from both sides met south of Richmond. The skirmish escalated, and the reinforced Federals took the lead during the afternoon. Encouraged by this success, Manson pushed his own brigade forward, despite Nelson's formal orders not to engage his still "blue" recruits. Night fell before the fight got too serious, but it gave Cleburne the opportunity to regroup. At dawn on the 30th, the Southerners attacked, immediately forcing Manson to fall back. Despite the arrival of reinforcements, and then of Nelson himself, the Federals eventually cracked, and the retreat of their inexperienced troops turned into a debacle . Over 4,000 Unionists, including Manson himself, were captured, Nelson was shot in the thigh, and the "Provisional Army of Kentucky" was virtually destroyed. Confederate losses amounted to less than a tenth of those of their enemies. They did, however, include Cleburne, injured superficially in the face.

Inflicted on the same day as the far greater in scale of the Second Battle of Bull Run, the defeat at Richmond plunged the North into anguish and consternation. Nothing seemed to be able to stop the Confederates from marching on Louisville to the west, or even Ohio to the north. Panic gripped the residents of Cincinnati, where the city's African Americans were forcibly conscripted into a navvies brigade to build fortifications. Buell had finally set off in pursuit of Bragg, but Morgan had singularly complicated his task:during a new raid, the Southern horseman had cut the railroad linking Nashville to Louisville. On August 14, he seized Gallatin, Tennessee, and caused the collapse of the railroad tunnel there. The line was cut for long months. This new hard blow made uncertain the outcome of the race between Bragg and Buell to reach Louisville first. Added to that of Maryland by General Lee, the invasion of Kentucky made September 1862 the darkest hour of the war for the Union .

Occupied Kentucky

Occupied Kentucky

On the evening of the Battle of Richmond, the advance guards of Smith's army had reached Lexington, where the population gave the Confederate troops a most favorable reception. Smith had taken care to take with him several thousand rifles which he intended to distribute to Kentuckians who would come to enlist in his army. In this area, his hopes were quickly dashed . The secessionist politicians and citizens of Kentucky multiplied the declarations of intent, but in fact, few were in a hurry to support the Southern cause with arms in hand. As James McPherson pointed out, the Kentuckians were clear-headed about the real scope of the Southern offensive, which was nothing more than a "full-scale raid ". Bragg and Smith had neither the manpower nor the material means necessary to sustain the state. The local population therefore cautiously remained on the reserve. Despite everything, Smith obtained a symbolic success, at the beginning of September, by occupying Frankfort, the capital of Kentucky. He then went on the defensive awaiting the arrival of Bragg, confining himself to pushing a few reconnaissances in the direction of Louisville and Cincinnati. The only noticeable effect of the latter was to push the Northerners to accelerate their military preparations in the region.

The military situation of the Union was, moreover, most worrying. In the race for Louisville, Buell was several days behind Bragg, a situation that caused Lincoln concern and led Halleck to regularly goad the chief of the Ohio Army. On September 14, Bragg reached the Louisville &Nashville Railroad near Munfordville, in central Kentucky, effectively intervening between Buell and Louisville. Munfordville was defended by a small force of 4,000 men, also inexperienced, and commanded by Colonel John Wilder. The latter nevertheless refused to surrender when the Southern vanguard reached his position, and his small, well-entrenched force repelled the Confederates when they launched an assault. The latter had cost the attackers more than 700 men, and Bragg carefully laid siege to the city. Wilder and his soldiers held out for four days , a respite that was to prove crucial in the rest of the operations. On September 16, Buell reached Bowling Green, about fifty miles southwest of Munfordville. Pressed to get it over with, Bragg ordered a new assault for the next day, but offered Wilder one last chance to surrender. Realizing that he would have to face the entire enemy army this time, the northern officer preferred to spare the lives of his men and capitulated.

At this point, Bragg was only a day or two ahead of Buell, and began to doubt his ability to take Louisville before his enemy could intervene. Smith urged him to attack Buell before the latter could be reinforced by the troops massing in Louisville, but Bragg rightly felt that he could not do so without the help of Smith's troops... For his part, Buell also avoided the fight carefully, so that when Bragg pretended to block his way to Louisville, the northern general was careful not to attack him . Meanwhile, Federal reinforcements continued to pour into Louisville and Cincinnati, further complicating the Confederate strategic situation in Kentucky. Bragg hesitated on what to do, and finally decided by swinging his army eastward, reaching Bardstown on September 22. He justified this by the need to join Smith, and the obligation to supply his army. In fact, the latter was now too far from its base in Chattanooga to hope to receive food from it by the roads that crossed the Appalachians, since the Federals controlled the railroads.

At this point, Bragg was only a day or two ahead of Buell, and began to doubt his ability to take Louisville before his enemy could intervene. Smith urged him to attack Buell before the latter could be reinforced by the troops massing in Louisville, but Bragg rightly felt that he could not do so without the help of Smith's troops... For his part, Buell also avoided the fight carefully, so that when Bragg pretended to block his way to Louisville, the northern general was careful not to attack him . Meanwhile, Federal reinforcements continued to pour into Louisville and Cincinnati, further complicating the Confederate strategic situation in Kentucky. Bragg hesitated on what to do, and finally decided by swinging his army eastward, reaching Bardstown on September 22. He justified this by the need to join Smith, and the obligation to supply his army. In fact, the latter was now too far from its base in Chattanooga to hope to receive food from it by the roads that crossed the Appalachians, since the Federals controlled the railroads.

Having made a wide detour to avoid having to face Bragg, Buell did not reach Louisville until September 26. However, it was enough to ward off the threat hanging over her. His army there joined the forces that William Nelson, quickly recovered from the wound received at Richmond, was organizing there. Nicknamed "Bull ("The Bull") because of his sanguine temperament and flowery language, Nelson was an uncompromising Unionist, often quick to suspect subordinates of disloyalty who did not do their duty well enough in his eyes - and he had to. little. Nelson thus had trouble with General Jefferson Columbus Davis, whom he relieved of his duties on September 22. The latter, despite his namesake with the southern president, was not a traitor, so much so that he digested very badly the insults uttered by Nelson against him. When the two men met on September 29 in a hotel in Louisville, the tone rose quickly. Nelson slapped Davis, and the latter took revenge by borrowing a friend's gun, with which he killed Nelson by putting a bullet in his heart. His murder deprived the Union of two otherwise competent generals at a crucial time – even though Davis was later released, continued his military career, and was never tried for his crime.