Victory over Napoleon at Waterloo , June 18, 1815, opens the way to the world supremacy of the British Empire . Indeed, it is not to Europe that Britain will now turn its efforts, but to the rest of the world. It is the construction of the Empire, certainly already begun the previous century, but which will be confirmed throughout the 19th century (until 1914), to contribute to the first globalization. A British Power which goes beyond the military and economic domains, aggregating on all continents a set of territories, united until 1931 by their allegiance to the British Crown.

Victory over Napoleon at Waterloo , June 18, 1815, opens the way to the world supremacy of the British Empire . Indeed, it is not to Europe that Britain will now turn its efforts, but to the rest of the world. It is the construction of the Empire, certainly already begun the previous century, but which will be confirmed throughout the 19th century (until 1914), to contribute to the first globalization. A British Power which goes beyond the military and economic domains, aggregating on all continents a set of territories, united until 1931 by their allegiance to the British Crown.

The British Colonial Empire

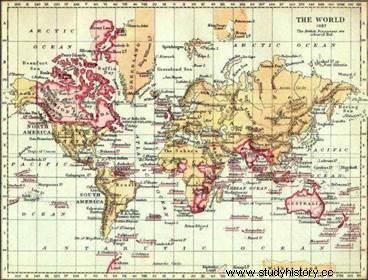

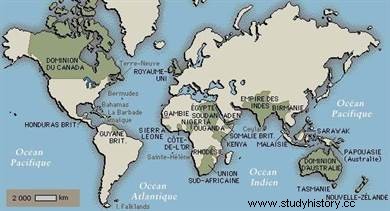

Defining the British world and the constantly shifting borders of the Empire during the long 19th century is a recurring historiographical debate. Without pretending to decide, we will say that the Empire mentioned here is made up of:Great Britain (including Ireland since 1801), the dominions (such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand), India ( "an empire within an empire"), the colonies of the Crown (mainly in South Africa), the protectorates (Egypt, Malaysia), the condominiums (over Sudan at the end of the century), the mandates for the aftermath First World War (Palestine) and the singular Sarawak. To this must be added the spaces where the Empire exercises a significant influence, what is called the informal Empire:these are the Ottoman Empire, Iraq, part of Latin America and China. To sum up, the British Empire until the beginning of the 20th century is almost the world! The factors of this power are very diverse, but the United Kingdom is dominant in many respects. It first benefited from a remarkable demographic growth since its population rose from 10.5M in 1801 to 37M in 1901! Its supremacy is then military and naval, essential to maintain the pax britannica . It makes it possible to exercise an imperial policy which leads to the apogee of the Empire in 1914 (33M km2, 400M inhabitants), even if the control of these territories is far from being direct. Its power is also exercised at the industrial, commercial and financial levels; Great Britain thus has the largest production, trading and lending capacity. In 1815, its GNP was already over 300M pounds; its coal production increased from 11M tons in 1800 to 225M in 1900! The Pound is the first world currency.

The factors of this power are very diverse, but the United Kingdom is dominant in many respects. It first benefited from a remarkable demographic growth since its population rose from 10.5M in 1801 to 37M in 1901! Its supremacy is then military and naval, essential to maintain the pax britannica . It makes it possible to exercise an imperial policy which leads to the apogee of the Empire in 1914 (33M km2, 400M inhabitants), even if the control of these territories is far from being direct. Its power is also exercised at the industrial, commercial and financial levels; Great Britain thus has the largest production, trading and lending capacity. In 1815, its GNP was already over 300M pounds; its coal production increased from 11M tons in 1800 to 225M in 1900! The Pound is the first world currency. Domination is more ideological, the British way of life sets itself up as a model. Some speak of a “moral empire”, with the fight against slavery and the importance of British missions all over the world. The model is also political, the Westminster model , which was exported to the dominions and as far as India (creation of the Congress party in 1885). However, we must not idealize this model, which sometimes creates a distorting mirror, as during colonial massacres (hunting of Aborigines for example)...

Supremacy is finally technical. The development of transportation (railroads, steamships) and communication tools (telegraph, Imperial Penny Post in 1898) promotes exchanges and the feeling of belonging to a community. This allows the transmission of the British model and stimulates migration within it.

Supremacy is finally technical. The development of transportation (railroads, steamships) and communication tools (telegraph, Imperial Penny Post in 1898) promotes exchanges and the feeling of belonging to a community. This allows the transmission of the British model and stimulates migration within it.

The symbol of this hegemony is perhaps the creation of time zones from the Greenwich meridian in 1880, marking the spatio-temporal centrality of Great Britain.

British naval and military power

The weight of the army and navy was more important for the British in the 19th century than for their French or German rivals; they are foundations of the Empire and of British rule. The navy in particular is essential to control the immense spaces that Great Britain claims to dominate. However, there is the problem of priorities because the means are not infinite:it is necessary to find the balance between defending the metropolis, defending the Empire, and maintaining the balance of power in Europe.

The Royal Navy first, to which the India Navy (from the East India Company) was linked until 1858. Its missions:to protect the British Isles and the sea routes; to be an instrument of influence and deterrence (in 1836, against France, off the coast of Tunisia for example; or gunboat policy in China); exercise scientific and technical functions (ethnology, botany, exploration in general). The Navy is very popular.

The army, meanwhile, is responsible for protecting the ports and major cities, the imperial borders, the settlers (against the natives, as in Jamaica in 1831, or in Ceylon in 1848), and to ensure the maintenance of order in the settlements (riots in Montreal in 1832, 1849 and 1853), as well as in the metropolis. This contributes to give it a less positive image than that of the Navy. It is moreover divided between men of rank recruited in the underprivileged classes (many of them Irish), and officers from the aristocracy (the fighting families ).  Britain's naval and military policy changed during the 19th century. Between 1815 and 1840 the imperial system was set up, in the post-french wars context. , which leads to a lower budget (from 45M to 8M between 1815 and 1837). The Empire develops its strategic bases and its points of support, such as Gibraltar, Singapore, Aden or Hong Kong. The period 1840-1880 is that of a reorganization made necessary by a series of confrontations. In 1853, 27,000 men were deployed in India, 23,000 in the West Indies and Asia, 50,000 in the settlements, which reduced the presence in Europe on the eve of the Crimean War (1854-1856) and revived the fear of the invasion with the coming to power in France of Napoleon III. Troops are then repatriated to mainland France, trusting the settlements (which do not necessarily agree). It was also during this period that the British gunboat policy developed, which involved shelling the coast to open markets.

Britain's naval and military policy changed during the 19th century. Between 1815 and 1840 the imperial system was set up, in the post-french wars context. , which leads to a lower budget (from 45M to 8M between 1815 and 1837). The Empire develops its strategic bases and its points of support, such as Gibraltar, Singapore, Aden or Hong Kong. The period 1840-1880 is that of a reorganization made necessary by a series of confrontations. In 1853, 27,000 men were deployed in India, 23,000 in the West Indies and Asia, 50,000 in the settlements, which reduced the presence in Europe on the eve of the Crimean War (1854-1856) and revived the fear of the invasion with the coming to power in France of Napoleon III. Troops are then repatriated to mainland France, trusting the settlements (which do not necessarily agree). It was also during this period that the British gunboat policy developed, which involved shelling the coast to open markets.

China was hit in 1860, as were Jamaica (1865) and Kenya (1875, against slave traders). At the same time, the Empire developed new networks:Suez Canal (1869), telegraph link (Malta-Alexandria in 1859; Great Britain-India in 1863; Great Britain-America in 1865). The last period is marked by the arms race and series of defeats:Isandlwana against the Zulus (1879), Maiwand against the Afghans (1880), plus the wars against the Boers (22,000 soldiers killed, cost of 300M pounds). British naval power was then challenged, and the Naval Defense Act (1891) is decreed so that Great Britain always possesses a fleet superior to the two other principal maritime powers put together.

Great Britain, at the beginning of the 20th century, decided to develop alliances to rationalize the defense of the Empire. It succeeds with France (1904) and Russia (1907), but fails with Germany, which has become its rival in the industrial field.

British expansion in Asia

When you think "British Empire “It is often India that comes back. However, if this was the jewel of the British world, the power of the latter was exercised throughout Asia, in different forms, and not always with ease, including in India.

The situation in Europe contributed to British expansion as early as the 18th century. Indeed, following the Seven Years' War, the Treaty of Paris (1763) allowed Great Britain to recover not only Canada, but also to consolidate its presence in the Indian subcontinent, even if France remained there. present (in Pondicherry).

The main tool for this expansion is a trading company, the East India Company , which, from its headquarters in Calcutta, exercises a commercial monopoly over the region. In 1784, the India act was signed between the British government and the Company. The EIC acted in concert with Indian authorities who allied themselves with the British and who provided troops, from the 1750s. Noble castes, the Sepoys, then made up the bulk of the armies of the Company. These alliances form the bedrock of the British Raj .

India, the jewel in the crown

The British "created" India as an empire, following the collapse of the Mughals and the last independent states (Third Maratha War, in 1817), then by the alliances local. In 1805 they conquered Dehli and put the Mughal lord under guardianship. Ten years later, it was Ceylon that fell under British rule and then, in 1816, an agreement gave independence to Nepal in exchange for access to the mountains. Throughout this period, the British played divisions between Indian lords, while relying on the EIC.

From then on, Britain controlled India from Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, confirming its power in the 1850s by defeating the Sikhs (annexation of Punjab) . In 1858, the EIC being dissolved, it was succeeded by a viceroy. Indeed, British domination was fragile, and in 1857 the revolt of the Sepoys, or Great Mutiny, broke out, a dispute within the Indian armies, where Muslims and Hindus met, and which jeopardized the British presence in the region. The repression is fierce, and the rebellion annihilated the following year. The government and Queen Victoria then decided to regain control by dissolving the EIC and placing India directly under British governance. In 1876, Victoria was "Empress of India".

The periphery of India

The success is more mixed in the regions surrounding India. If, as we have said, Nepal and Ceylon are finally controlled more or less directly, the situation is much more difficult in Burma and Afghanistan.

As early as the late 1830s, the British Empire struggled in its drive to control Afghanistan, to counter Russian expansion in the region through the constitution of a glaze. In 1842, it is the famous disaster of Khyber Pass, where the British army is exterminated. It took more than thirty years, and the crisis with the Russians in the Balkans, for the Empire to try again to conquer Afghanistan. The second Afghan war (1878-1881) ended in another failure (with the battle of Maïwand, where Conan Doyle's Watson was wounded). However, the Russian advance eventually led the Emir of Kabul to sign agreements with the British in the early 1890s.

In Burma, the problems began as early as the end of the 18th century, and in 1818 the Burmese took Assam (east of India). The British recover it following an agreement reached after the first Burmese war (1824-1826), the stake of which is the control of the Bay of Bengal. In 1852, a second war allowed the Empire to take control of Rangoon. Then, at the end of the 1880s, Upper Burma was attached to the Indian Empire to counter the French advance in Indochina. The British then decided to consolidate their positions in Southeast Asia.

In the North, finally, there is the problem of Tibet around Sikkim. The tensions, in which China enters, last until the beginning of the 20th century. In 1904, a treaty was finally signed in Lhasa, which opened Tibet to British trade.

British influence in Southeast Asia

The British presence in Malaya dates from the late 1780s. The region is made up of princely states and sultanates with which the Empire plays the same game as in India , a mixture of alliances and offensives.

It was again the European context that contributed to British expansion. The Dutch, present in Southeast Asia since the 16th century, controlling Malacca among others, allied themselves with the French in 1795, justifying British intervention. The Congress of Vienna (1815) drives the point home, despite some retrocessions. In 1819, the strategic port of Singapore was created, consolidated in 1824 by the acquisition of Malacca, following exchanges of territories with the Dutch. From 1841, the British settled in Sarawak, but it took forty years for this small state to be annexed, just like Borneo and Brunei. Finally, at the beginning of the 20th century, the last Malay states and Siam also gave up and passed under British protectorate.

Relations with China

Relations between the Empire and China are more complex, although the Middle Empire is one of the main objectives of the British.

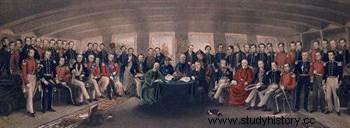

The Opium War, sometimes explained by the loss of the EIC's monopoly on trade in the region, broke out in 1840, following the diplomatic failure to "open" China to trade. By the Treaty of Nanjing (1842), the British obtained Victoria Island (Hong Kong) and the opening of five Chinese ports (including Shanghai).

The situation became more complicated with a threat of civil war in China, following the installation of the Taipings in Nanjing between 1843 and 1845. This announced the revolt which broke out in 1851 and put hurt China's ruling dynasty, the Qing. The British, but also the French, then tried to take advantage of it, but the situation was hardly favorable to trade, especially when other "opium wars" broke out in the years 1858-1860, one of which the Imperial Summer Palace is attacked. Eventually, the Europeans helped the Qing crush the Taiping Rebellion in 1864-1865. This allows them to see China open up, constrained, to trade and “free trade”.

The end of the century confirms the domination of China, in a context of competition between Europeans, especially since the Qing failed in Japan (1894-1895) and were even more weakened . Great Britain is the creditor of the Middle Empire, and installs its zones of influence and its points of support on the Chinese coasts, entering little inland. This British effort is always to be situated in the "Great Game", in particular with the Russians, as confirmed by the agreement signed with Japan in 1902. The Boxer Rebellion (including the siege of Beijing in 1900) and the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, which gave way to the Republic of China, did not change the situation.

Asia and the Indian jewel are therefore a major part of the British Empire, especially before its conquest of Africa. We can see the diversity of the systems of domination, more or less indirect, that Great Britain puts in place to impose its influence and its trade of free trade.

"The Eastern Question"

The Middle East holds a special place in the politics of the British Empire in the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century, until the First World War. Although it is not strictly speaking part of the "British world", it is nonetheless an important, even central, issue in the Great Game with Russia, then during the war, as the adventure shows by Lawrence of Arabia . From the Eastern Mediterranean to Afghanistan, via Egypt and the Persian Gulf, discovery of a "Greater Middle East" under British influence until the 1930s.

Although Great Britain had dominated the western Mediterranean for a long time (taking Gibraltar in 1704), it was not until the end of the Napoleonic wars and the Congress of Vienna (1815) that 'it really looks to the eastern Mediterranean, the Levant. However, it must first settle "the Eastern question", particularly in the context of a growing rivalry with Russia. This eastern question primarily concerns the Ottoman Empire which, from the end of the 18th century (loss of Crimea to Russia in 1774), began to fall into a negative spiral, which continued to worsen in the 19th century.

The Greek War of Independence was a turning point because, after a certain neutrality in the early 1820s, the European powers – among which, of course, Great Britain – came into game in 1827, and contributed to the independence of Greece in 1830. But the British had to react the following year to the coming to power in Egypt of Muhammad Ali, then in 1833 to the alliance between Russia and the Turkey. A loss of Empire influence over Egypt threatens British interests in India, and according to Lord Palmerston and the Foreign Office the question of the straits must remain European.

Between military interventions and diplomacy

There then began intense diplomatic and military activity by the British to maintain a certain balance in the Levant. First, to restrict the power of Muhammad Ali's Egypt, with the capture of Aden in 1839. Then, the following year, as tensions with France increased around the Egyptian question, a rapprochement took place with Russia at the Treaty of London. This makes it possible to break the ambitions of Egypt in Syria, and thus to help the Ottoman Empire against the ambitions of Muhammad Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha. Meanwhile, Britain and La Porte signed the Treaty of Balta Liman (1838), strengthening British economic power in the region, and its influence over Turkey.

During the 1840s, Great Britain increased this influence in the Levant thanks to free trade and a network of regional clienteles (Druze, Armenians, etc.). The main rival then seems to be France, which is beginning to experience success in the western Mediterranean. The French scares developed among the British , which led, among other things, to the strengthening of the fortifications of Malta (under the control of the Empire since 1800). However, it is once again Russia that is changing the game.

First during its conflict with France over the management of the Holy Places (1852), then especially when Russia invaded the Ottoman provinces of the Danube in 1853. the start of the Crimean War, in which Great Britain engages alongside France and the Ottoman Empire. Indeed, the British do not want Russian influence in the region, which could threaten as far as Persia and, moreover, they want the reforms led by La Porte, positive for trade and therefore the economic power of the country. 'Empire. The Treaty of Paris (1856) put an end to the war, from which France and Great Britain emerged victorious, reinforcing their presence in the region, but also their guardianship over the Ottoman Empire.

The end of the 1870s was a new period of crisis for Turkey:revolt in Herzegovina, then in Bosnia and Bulgaria (1875-1876), bankruptcy in 1876, declaration of Russia's war the following year, ... German Chancellor Bismarck convened a congress in Berlin in July 1878. The independence of Serbia, Montenegro and Romania was ratified, while "Greater Bulgaria" was split into two entities (Bulgaria and Rumelia). The British, who participated in the congress with Disraeli to counter Russian influence, are satisfied and even obtain trusteeship over Cyprus. But this crisis showed that the Ottoman Empire was truly unreliable, prompting the British Empire to “ditch Istanbul for Cairo” .

Egypt:the strategic key

If the Muhammad Ali period had been detrimental to British influence in Egypt, the late 1850s marked a new turning point. The Empire then had France as a rival, around the question of the Suez Canal, the project of which was viewed with a dim view by Lord Palmerston. However, Foreign office policy fails to prevent the success of the project in 1869, and the choice is then made to join it with the purchase from the Egyptian khedive of its shares in 1875. France has to do with it, even if it still remains the majority in the Suez Canal Company.

In fact, Egypt became a British protectorate, even if it was only officially in 1914. Great Britain took advantage of this position to control German ambitions in the region at the beginning of the 20th century, and to serve British interests in the question of the straits. Egypt obviously held a decisive place during the outbreak of the First World War.

From Iraq to Afghanistan

The Great Game that pits the British against the Russians is not only being played in the eastern Mediterranean, but also on the doorstep of India. The Empire wants to counter the advance of Russia by creating a glacis around its Indian jewel but, from the 1830s, the difficulties accumulate because of the resistance of Afghanistan. First came the Khyber Pass disaster (1842), then the Maiwand disaster (1880). In the end, it was through diplomacy that the British prevailed by convincing the Emir of Kabul of an agreement in the early 1890s.

In Mesopotamia, where the Ottoman Empire only exercised symbolic control, Great Britain had been present since the second half of the 18th century (Basra in 1764, Baghdad in 1798). The region is essential in the protection of the route to India, and the British do not hesitate to transform the coastal emirates of the Persian Gulf into protectorates, often under the pretext of fighting piracy. The agreements with Kuwait, signed in 1899, are in this spirit. We can then speak of a “pax britannica in the Arabian Peninsula.

But German rivalry in the 19th century threatened British interests; these are the projects of the Baghdadbahn , or the Hejaz Railway in the early 20th century. In fact, it was not until the First World War that the British really took the lead in the region.

War in the Middle East:Lawrence of Arabia

When the First World War broke out, the Middle East was a fundamental issue for Britain for many reasons. Beyond the fight against the Ottoman Empire, an ally of Germany, it is necessary to position itself in the region to continue to control the route to India, but also to catch up on some new strategic issues such as oil. Compared to the Americans, the British only “placed themselves” in the second half of the 19th century, and at the beginning of the 20th, despite the creation of Shell in 1833. In May 1914, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, buys 51% stake in Anglo-Persian Oil Company (created in 1909) to control a resource that had become essential for the British fleet (switched to oil in 1913), and therefore for the Empire. Most of the deposits are then in Persia.

The beginnings of the war in the Middle East were not very good for the British, with in particular the disaster Dardanelles in 1915. Even in Egypt, their power was contested and they had to establish martial law in 1914. From the end of 1914, troops from India arrived in Iraq, but they were unable to win and, worse, were defeated in April 1916! General Allenby then transferred his efforts to the Sinai, then to Palestine, taking Gaza and Jerusalem between March and December 1917. He was able to benefit from the open front in Arabia thanks to the diplomatic and then military action of Lieutenant Thomas Edward Lawrence, known more later as Lawrence of Arabia. This one is volunteered in 1914, and he works in Intelligence in Cairo.

The beginnings of the war in the Middle East were not very good for the British, with in particular the disaster Dardanelles in 1915. Even in Egypt, their power was contested and they had to establish martial law in 1914. From the end of 1914, troops from India arrived in Iraq, but they were unable to win and, worse, were defeated in April 1916! General Allenby then transferred his efforts to the Sinai, then to Palestine, taking Gaza and Jerusalem between March and December 1917. He was able to benefit from the open front in Arabia thanks to the diplomatic and then military action of Lieutenant Thomas Edward Lawrence, known more later as Lawrence of Arabia. This one is volunteered in 1914, and he works in Intelligence in Cairo.

In 1916, he was sent as an emissary to the Emir Fayçal when the Arab revolt broke out. Well accepted by the Arabs, he was one of the leaders of the offensives in the Hejaz, where he distinguished himself by isolating the Turkish garrison of Medina, then taking the port of Aqaba in July 1917. He then joined Allenby in Palestine then, with its Arab allies, took Damascus and Aleppo in October 1918. Meanwhile, a new British offensive enabled the capture of Baghdad (March 11, 1917). But Britain's involvement in the region had far-reaching consequences long after the war.

Zionism and Arab nationalism

The Zionist project appeared at the end of the 19th century, in the context of the pogroms in Eastern Europe, which provoked a first alya in Palestine, in the years 1880-1890. The founder of Zionism, Theodore Herzl, wanted to create a Jewish state, as he affirmed following the Congress of Basel in 1897. This project was quickly seen as a threat by the Arabs, especially after the first alya . Someone like Rachid Rida (who will inspire the Muslim Brotherhood), from 1902, sees in Zionism a project aimed at seizing political sovereignty in Palestine. The second alya intervened in 1914, passing the yishuv (Jewish home) to more than 80,000 people. The British then engage in a double game, supporting Zionism on the one hand and Arab nationalism on the other.

The Sykes-Picot agreement, first, signed in May 1916, just before the Arab revolt, by the Frenchman Georges Picot and the Briton Mark Sykes. Ratified by the Foreign Ministers of the two countries, it is also subject to Russian approval. This agreement is intended to be in line with the discussions between Sharif Hussein and McMahon, and it paves the way towards "an independent Arab state or a confederation of Arab states" which France and Great Britain would be prepared to recognize. However, the agreement remains secret and Hussein's supporters ignore it when they launch their revolt. The other aspect of the Sykes-Picot agreement is to make Palestine a regime of internationalization guaranteed by Russia, while France and Great Britain claim this territory…

The evolution of the war is changing the situation, especially in Palestine. While the Zionists had hoped for a time for the support of the Ottomans, they finally turned to the Allies, with for example Jewish fighters engaged as a unit in the imperial army. Then, it was British officials who began to take an interest in the advantages that support for Zionism could bring, especially in relations with the United States.

Russia's withdrawal from the war was a game-changer for the Sykes-Picot agreement, it was the watershed moment that led to the Balfour Declaration of November 2, 1917. It is addressed to Lord Rothschild, of the English Zionist Federation, and supports the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine. Arab populations in the region are referred to as “non-Jewish communities” , whose religious and civil rights must be guaranteed, but their status as a people and their political rights are not mentioned.

La situation se complique après la guerre, dans le contexte des rivalités franco-britanniques dans la région. Les Arabes souhaitent l’unification de la Syrie, du Liban et de la Palestine avec comme roi Fayçal, fils du chérif Hussein. Mais la conférence de San Remo en avril 1920 attribue les mandats de Syrie/Liban et de Palestine/Mésopotamie respectivement à la France et à la Grande-Bretagne. Les violences commencent en Palestine. Un soulèvement nationaliste éclate en Irak en 1920, et les Britanniques en profitent pour donner le trône à Fayçal en 1921, en compensation de la Syrie, et la Transjordanie à son frère Abdallah. En Arabie, les Britanniques perdent la main quand, en 1925, leur allié Hussein est défait par les Saoud, dont les Américains vont rapidement se rapprocher…

En Palestine, les tensions ne cessent de monter entre Juifs et Arabes à mesure que l’immigration juive augmente (la population juive a doublé entre 1919 et 1929). Les Britanniques s’engagent à protéger les Palestiniens non juifs, et en 1930 tentent en vain de limiter l’immigration juive. Le conflit israélo-palestinien est en germe.

La situation en Egypte n’est pas tellement meilleure. L’influence et la présence britanniques ont exacerbé le nationalisme, et Saad Zaghoul fonde le parti Wafd pour réclamer l’indépendance. Celle-ci est proclamée en février 1922, et le sultan Fouad devient roi d’Egypte, contre l’avis du Wafd cependant. L’indépendance ne signifie pas la fin de la tutelle de la Grande-Bretagne, ni des tensions, et la création des Frères musulmans par Hassan el-Banna en 1928 se fait en grande partie sur le rejet des Britanniques.

Le Moyen-Orient tient donc une place à part dans le monde britannique au XIXe siècle et dans la première partie du XXe siècle. Sa position stratégique, sur la route des Indes, pousse l’Empire à intervenir régulièrement et à se maintenir par tous les moyens (souvent économiques, et de plus en plus militaires), dans le contexte des rivalités avec la Russie, mais aussi la France, et évidemment l’Empire ottoman. Les décisions politiques de la Grande-Bretagne, notamment aux débuts du XXe siècle, en Palestine, en Egypte ou en Irak, ont des conséquences jusqu’à aujourd’hui.

L' Empire britannique en Afrique

L’Afrique tient une place moins importante que l’Inde ou le Canada dans le monde britannique du XIXe siècle, mais elle devient la grande affaire des années 1890-1900, notamment dans le contexte d’une rivalité avec la France. La pénétration britannique dans le continent africain est donc lente, dictée par des raisons très diverses, et pas sans opposition, l’exemple de la guerre des Boers étant loin d’être le seul. Au début du XXe siècle, l’axe Le Cap-Le Caire est constitué, et la Grande-Bretagne exerce son influence sur une grande partie de l’Afrique.

Les premiers contacts avec l’Afrique

Dès la fin du XVIe siècle, des marchands britanniques sont présents en Gambie (James Island), grâce son fleuve navigable. La Compagnie Royale Africaine est fondée en 1678 et construit un fort en Gambie. En 1787, la Sierra Leone est créée pour accueillir des esclaves affranchis; elle devient colonie britannique en 1808.

La lutte contre la Traite et l’esclavage devient un prétexte pour intervenir en Afrique. En 1833, l’esclavage est aboli dans les possessions britanniques, et les abolitionnistes décident d’imposer cette décision aux autres puissances européennes, mais aussi aux souverains africains. A partir de la Sierra Leone, l’escadre British West African Squadron a pour mission d’arraisonner les navires transportant des esclaves. Cette politique permet aux Britanniques de s’installer plus solidement dans la région, y compris dans l’actuel Ghana (Gold Coast ). Puis, elle se diffuse dans toute l’Afrique, et est en partie à l’origine de la guerre des Boers. Nous y reviendrons.

L’autre moyen pour découvrir l’Afrique, et qu’il ne faut pas négliger, est l’exploration. Dès 1770, James Bruce découvre les sources du Nil bleu, puis Mungo Park explore le Niger au début du XIXe siècle. La cité de Tombouctou est découverte par Alexander Gordon Laing en 1825, tandis que Richard et John Lander descendent le Niger jusqu’à la mer (1830). En 1862, John Speke et James Grant identifient la source du Nil au lac Victoria et, deux ans plus tard, David Livingstone atteint le lac Nyassa, puis les Grands Lacs au début des années 1870.

Entre explorations et installations progressives, manœuvres militaires et diplomatiques, les Britanniques rencontrent de plus en plus de résistance.

Les résistances à la pénétration britannique en Afrique

L’ambition de la Grande-Bretagne en Afrique se heurte à plusieurs résistances. D’abord des souverains africains qui ne veulent pas cesser l’esclavage. C’est le cas, par exemple, avec le roi de Lagos (Nigéria), Oba Kosoko, qui refuse de stopper la Traite. Les Britanniques prennent ce prétexte pour intervenir en aidant le frère du roi, Oba Akitoye, à recouvrer son trône. Cela conduit à l’installation d’un consul britannique à Lagos en 1853, puis à la création du protectorat en 1861.

L’autre grande résistance à l’ Empire Britannique est plus connue :ce sont les Zulus. Ces derniers menacent les Boers, qui ont accepté d’être intégrés à l’Empire en 1877. Deux ans plus tard, la Grande-Bretagne doit régler « le problème zulu ». Cela commence très mal par la débâcle d’Isandhlwana (22 janvier 1879), où plus de 20 000 guerriers zulus massacrent un millier de soldats britanniques. Malgré la résistance à Rorke's Drift quelques heures plus tard, il faut attendre le 4 juillet de la même année pour que les Zulus soient définitivement défaits, à la bataille d’Ulundi.

Le cas du Basutoland, enfin, est très singulier. Sous Moshoeshoe, le royaume de Sotho bénéficie d’une assemblée représentative, et n’est ainsi pas spécialement influencé par la modernité prônée par la Grande-Bretagne, et qui l’aide en partie à accroître son emprise en Afrique. Le royaume de Sotho résiste donc un temps, non seulement aux Britanniques mais également aux Zulus et aux Boers. Ils doivent toutefois demander l’aide de la Grande-Bretagne contre ces derniers en 1868, et deviennent ainsi un protectorat. Trois ans plus tard, ce qui est à présent le Basutoland est mis sous l’autorité du Cap, provoquant le mécontentement des habitants. En 1881, ils se soulèvent contre l’Empire et ont gain de cause en obtenant qu’aucun colon blanc ne vienne s’installer sur le territoire. Le Basutoland ne sera ainsi jamais annexé par les Britanniques, et les chefs locaux y conserveront un pouvoir important.

La guerre des Boers

Entre 1795 et 1815, le Cap passe successivement entre les mains de la Grande-Bretagne et des Pays-Bas, avant de définitivement devenir colonie britannique. La politique impériale est alors marquée par une volonté d’angliciser le territoire par l’immigration et l’introduction des lois britanniques. Cela provoque évidemment de vives tensions avec les colons hollandais, appelés Afrikaners ou Boers.

C’est néanmoins la question de l’esclavage qui met véritablement le feu aux poudres. Refusant d’émanciper leurs esclaves, les Boers entament le Grand Trek (1836-1844), une migration vers le Natal, puis l’intérieur des terres. Les Britanniques reconnaissent l’Etat libre d’Orange et du Transvaal dans les années 1850. Mais en 1877, la Grande-Bretagne annexe le Transvaal, en profitant de la menace zulu. Une fois celle-ci écartée, les Boers se rebellent contre les Britanniques, qu’ils battent à Majuba, le 6 mars 1881.

Scramble for Africa

Les anglais s’installe véritablement en Afrique à partir des années 1880. Il se base sur ses deux principaux points d’appui, Le Caire et le Cap, et sur les décisions de la conférence de Berlin (1884-1885). Une fois encore, comme souvent dans l’expansion de l’Empire, le libre-échangisme est un moyen ou un prétexte pour prendre possession de façon plus ou moins directe de territoires. Cet axe Cape to Cairo est notamment défendu par Cecil Rhodes, un entrepreneur qui a fait fortune dans le diamant.

En Afrique de l’Ouest, c’est la National African Company qui mène l’expansion, avec un protectorat commercial dans le delta du Niger (1885) et en Gambie (1893). Le concurrent principal est alors la France. L’Afrique orientale est une rivalité contre l’Allemagne, mais la Grande-Bretagne met la main sur l’Ouganda dans la première moitié des années 1890, puis au Kenya. La création du condominium du Soudan, déjà évoquée, se situe dans le prolongement. Au Sud, outre le Basutoland, on peut citer le Bechuanaland (Botswana), protectorat en 1885, puis la Rhodésie du Sud (Zimbabwe) et du Nord (Zambie), toujours sous l’influence de Cecil Rhodes…Enfin, la réunion de deux territoires sous le nom de Nigéria en 1914 achève l’expansion britannique en Afrique.

Premières installations à visée commerciale, puis lutte contre l’esclavage, explorations, promotion du libre-échangisme et enfin actions plus strictement militaires en pleine période de concurrence coloniale entre Européens, ont ainsi conduit à faire de l’Afrique une part non négligeable, même si tardivement intégrée, de l’ Empire britannique et dont les conséquences ont été décisives au XXe siècle, notamment en Afrique du Sud. En revanche, des recherches récentes effectuées par des historiens de Paris 1 tendraient à réfuter l’idée longtemps diffusée selon laquelle les Britanniques auraient eu une influence décisive sur la définition des frontières des pays africains, enjeux de conflits contemporains. Dans une grande partie des cas, ils se seraient grandement inspirés de frontières existantes.

La puissance économique et industrielle de l' Empire britannique

Au XIXe siècle, l’Empire est la première puissance commerciale mondiale en volume. Elle le doit d’abord à son industrialisation, dès la fin du XVIIIe siècle et jusqu’aux années 1840. C’est la période de la révolution industrielle, avec l’organisation de la production, du développement de l’industrie du textile, des biens de consommation, puis du chemin de fer et de la métallurgie.

La balance commerciale est déficitaire, condition indispensable cependant à un bon système international de balance des paiements. Le Gold standard assoie la domination de la livre, monnaie indexée à l’or, ce qui permet à la City de devenir la première place financière mondiale, et aux banques britanniques d’être les instruments de cette puissance.

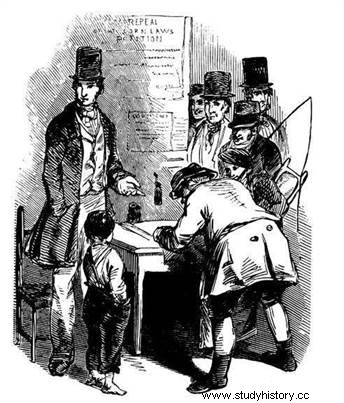

Les années 1840 voient aussi la doctrine du libre-échange s’imposer. En effet, contrairement aux idées reçues, le processus est long et les débats politiques animés. L’agriculture est sacrifiée au bénéfice de l’industrie (abrogation des corn laws en 1846), et sont votées l’abrogation des actes de navigation (1849) et des préférences impériales (1850). La Grande-Bretagne essaye ensuite de convertir d’autres pays au libre-échange; c’est par exemple le traité Cobden-Chevallier, signé avec la France en 1860. La Dépression des années 1870 freine toutefois l’élan, et les années 1930-31 voient le retour du protectionnisme, suite à la crise, mais également à cause de la concurrence allemande et américaine.

Le XIXe siècle, jusqu’à la Première guerre mondiale, est bien le siècle de l’ Empire britannique. Celui-ci assoit sa domination d’une manière originale, souvent indirecte, principalement par l’intermédiaire du commerce et d’une politique impériale qui ne cesse d’évoluer et de s’adapter au cours du siècle.

Bibliographie

- P. Chassaigne, La Grande-Bretagne et le monde de 1815 à nos jours, A. Colin, 2009.

-J. Weber, Le siècle d'Albion :L'Empire britannique au XIXe siècle 1815-1914. Indes savantes, 2011.

- F. Bensimon, L'Empire britannique. « Que sais-je ? PUF 2014.