There are moments in history when some people appear, shooting stars themselves, act, leave a strong mark on it and then disappear into its oblivion, as if they never existed.

One such story is that of Xanthippus of Lacedaemon, who from a humble mercenary, driven from his homeland by deprivation and injustice, found himself in a single moment, commander-in-chief of the army of the other great superpower of his time, Carthage, fighting with the best army of the ancient world, the Roman.

On the brink of destruction

In 256 BC the First Carthaginian War was raging. But the Carthaginians had suffered a series of defeats at sea and on land. After their crash at sea, the Carthaginians were confined to the African coast. And the Romans decided to transfer the war to Africa, striking the "beast in its lair" and forcing their opponents to deal with the security of their country, leaving the conquest visions for Sicily aside.

Indeed the Romans landed forces in the area of Cape Bon and besieged the city of Aspida, following the plan that the Greek Agathocles had also used when he had also attacked Carthage some 50 years earlier.

The Carthaginians, after their defeat, believing that the Romans would attack Carthage directly, kept their forces in their city and did not venture to engage the Romans. Thus the Romans took the city of Aspida undisturbed and plundered the whole country, taking 20,000 prisoners and rich booty, undisturbed.

This attitude of the Carthaginians led the Romans to the decision to leave only part of their army in Africa, led by one of the two governors, Marcus Attilius Regulus. The rest of the Roman forces left for Italy and Sicily.

The Roman general remained on the Tunisian coast with 15,000 infantry, 500 cavalry and 40 ships. Despite this, he developed great activity and continued to savagely plunder the country, even besieging the important city of Ady. Faced with these developments, the Carthaginian leaders were also forced by the pressure of public opinion to take action. Besides, they outnumbered their opponents. They even elected three generals, Amilkas, Asdruvas and Bostarus, and assigned them to attack the Romans and lift the siege of Adys.

The Carthaginian generals did move, but fearing the invincible Roman infantry, they ordered their forces on a hill, near Ady, completely unsuitable for the development of their forces and especially the weapons in which the Carthaginians traditionally excelled, i.e. cavalry and war elephants. The Romans realized the mistake of the opponents and attacked them there, on the ground they could not fight. The outcome of the battle was as expected. The Carthaginians were crushed and those who survived, together with their generals, returned humiliated to Carthage.

The situation was now absolutely critical for the Carthaginians, who had now lost both their army and the ability to defend their own city. The Romans, after their victory, occupied Ady, but also the city of Tunis - today's Tunis - limiting their opponents even more.

Greek mercenaries

The Carthaginians then resorted to the massive recruitment of mercenaries from Greece, whom they considered to be the most worthy fighters. In the meantime, the situation for the Carthaginians worsened, since the Roman victories also turned some of their Numidian subjects against them.

In the summer of 255 BC the Greek mercenaries arrived in Carthage, with whom the Carthaginian forces joined, forming an army of 12,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry. The Carthaginians also had about 100 African war elephants.

In the meantime the Carthaginians tried to negotiate with the Roman general, but the terms he imposed on them were so heavy that they were not accepted. Despite this, despair had taken over the Carthaginians, who were afraid to fight again with the Romans, because if they were defeated, Carthage would be left completely defenseless.

While the doubt about the practice tormented the Carthaginian generals, a simple soldier from the Greek mercenaries, Xanthippus of Lacedaemon, judging the events with his colleagues, decided that the cause of the defeat of the Carthaginians was not the Romans, but himself the self! Stunned, his colleagues gathered around him and heard him develop his arguments in such a logical manner that they were soon convinced.

This discussion soon went beyond the boundaries of the camp and reached the ears of the citizens, causing intense discomfort for the generals themselves, but also great interest in the views of the humble mercenary. Faced with the pressure of public opinion, the Carthaginian authorities were forced to invite Xanthippos to explain his views before them.

Xanthippus actually appeared before the lords of the city and told them again that the reason for their defeat was not the Romans, but their own errors and not exploiting the advantages of their army, while exploiting the disadvantages of the opponent. With great courage the Spartan soldier asked the council to entrust him with the chief strategy and allow him to fight the Romans. In their desperation and under the pressure of necessity, the Carthaginian lords accepted, despite the discomfort of their generals, who had to be placed under the orders of their former soldier!

Xanthippos, however, a soldier from the moment of his birth, as a Spartan, knew how precarious his position was and to win the support of the citizens he ordered the army to come out of the walls and perform a series of exercises, under the eyes of the inhabitants.

In the field of exercises, the Greek general now showed his worth and his superiority over the Carthaginian generals. After this demonstration, the Carthaginian citizens were impressed and began to rhythmically shout his name from the walls, demanding that the rulers allow the Greek to attack the Romans directly.

Xanthippus' plan had succeeded. The lords gave their approval and the next day the army, under the leadership of Xanthippus, marched to meet the Romans. Xanthippus sought to engage the Romans on an open field, where his superiority in cavalry and elephants would ensure victory. The Roman infantry, i.e. the best part of the enemy army, would defeat it, in a second year, under the conditions he would have created, after first his cavalry would have settled its accounts with the corresponding Roman.

After a short march the army of Xanthippus approached the Romans. Marcus Attilius Regulus, in view of the threat, gathered his scattered army and moved to meet the enemy, with the air of a victor. The Romans reached a distance of about 2 km from the army of Xanthippus, in the middle of the Tunisian plain.

The critical conflict

Regulus, it is true, did not believe that the Carthaginians would dare to give battle again. This was the first surprise he suffered. The second had to do with Xanthippus' choice of battlefield, which clearly favored the more flexible army, which of course was the Carthaginian. However, Regulus had so much confidence in himself and the infantry that he did not hesitate to risk giving battle.

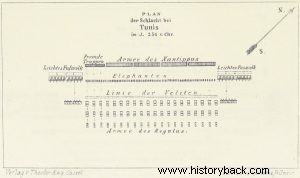

Numerically the two opposing armies were almost evenly matched, with 16,300 Carthaginians facing 15,500 Romans. Their differentiation was qualitative. The Roman general, in order to counter the advantage of his opponent in cavalry and elephants, ordered his infantry in dense formation and his few cavalry in the wings.

Regulus' aim was to neutralize the elephants with his elite infantry, who would then, in ram-like fashion, break through the Carthaginian phalanx behind them. But Xanthippos had an opposite opinion. And indeed he ordered his elephants in the center, with the intention of breaking with them, or at least causing serious bleeding to the Roman infantry, but he ordered his infantry far back, so that in case of an accident the elephants would not disperse the friendly phalanx.

He also ordered his cavalry on either side of the elephants, with the task of breaking up the Roman cavalry and then dealing with the flanks of the dense Roman mass of infantry. On the right of the phalanx and ahead of the Carthaginian phalanx Xanthippus ordered 2,000 mercenaries, rather Greeks, with the intention that they alone should support the elephants and be a decoy for the Roman infantry , while at the same time he deployed all his psilis (acrobolist light infantry) in front of the cavalry and elephants, with the mission of supporting these divisions.

Thus arrayed, the two opposing armies watched each other for a while, until Regulus decided to attack, throwing against the elephants his elite light infantry, the Velite spearmen, who specialized in dealing with these megabeasts. In response Xanthippus ordered his front line to attack simultaneously. A fierce battle began in the center, initially between the Psilis and the Velites.

But the first ones also had the support of elephants and in this way they overcame the Romans. Thus the field between the elephants and the Roman legions was left empty. Xanthippus immediately ordered an elephant charge against the Roman infantry. Soon the legionnaires found themselves facing the beasts and naturally suffered overwhelming losses. However, the great depth of the Roman line allowed them to withstand the attack of the elephants.

In fact, an elite Roman division of 2,000 men moved against the bait laid by Xanthippus, the mercenaries, who were ordered to fight fiercely for a while and then to flee, supposedly on the run. So it happened and the victorious Romans, at that point, pursued the "defeated", but leaving a first-class gap on the left flank of the dense Roman mass. Into this gap penetrated the Carthaginian cavalry, which had easily crushed the few Roman cavalry and surrounded the entire army of Regulus. Soon the situation for the Romans became tragic.

The men were trampled by the elephants and the survivors were finished off by the Carthaginian infantry that followed. Those Romans who attempted to escape to the plain were mercilessly slaughtered by the Carthaginian cavalry. Only the body of 2,000 Romans who had pursued the mercenaries caught up and fled and were saved.The entire rest of the Roman Army was annihilated, except for Regulus and 500 men who were captured. 13,000 Romans fell in the battle, against only 800 of the Carthaginian Army.

Xanthippus had triumphed by applying a maneuver later "borrowed" by Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae (212 BC). The victorious general entered the city where he was received with delirium of enthusiasm. Nevertheless, the clever Spartan understood that glory is fleeting and envy a product of it. Therefore, having received a great reward from the Carthaginians, he left them in secret and went to Egypt, enlisting in the service of the Greek Ptolemies!

According to another version, however, Xanthippos did not leave, but led the Carthaginian Army to Sicily and was murdered there by the Carthaginian generals. However, this view is not historically documented and is probably not correct.