On April 7, 1941, colonel Thomas Pentzopoulos was in the Monastery of the then Yugoslavia. The colonel was emissaries of the Greek General Staff (GS) with the aim of clarifying the situation and establishing liaison with the Yugoslav general staff. Until then, the information that the Greek headquarters had was extremely confusing and largely contradictory. The GS had information that German forces had broken through the Yugoslav defenses especially in the area north of the forts.

On the contrary, the British intelligence service and the Yugoslav military attaché in Athens assured that not only that nothing like this had happened, but also that the Yugoslav forces had advanced into Bulgarian territory.

Colonel Pentzopoulos, from the moment of his arrival at the Monastery, encountered images of dissolution. Arriving in Velessa, he met with the general commander of the "Bregalnitsa" division, which had been disbanded. The Greek officer moved on his own initiative to Skopje, but never arrived as the city was occupied by the Germans.

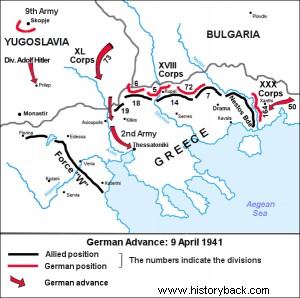

Pentzopoulos reported about it to the General Assembly, but his report was not evaluated with the immediacy that the times demanded. It seems that the rapid collapse of the Yugoslav army took the Greek leadership by surprise. same as Yugoslav. However, the General Assembly ordered the modification of the arrangement of the Greek-British forces in Central Macedonia, so that it forms front to the North.

At the same time he ordered other movements of the few available units to cover the Florina corridor from where the Germans could flank the Greek troops fighting in Northern Epirus. But all these were half measures.

These moves were both late and insufficient. From the moment of the first report by Peentzopoulos, on April 7, corrective actions should have been ordered and mainly the preparation for the retreat of the Greek forces from Northern Epirus , or at least the forces of the Western Macedonian Army Division (WAM) to create a diversionary and strong connection with the Cavalry Division (MI) which took over the coverage of the right flank of the Greek forces in Northern Epirus.

To ascertain the situation, the Greek General Assembly dispatched another officer to Yugoslavia on April 9. Major Theodosios Papathanasiadis was sent. Papathanasiadis, after an accident, arrived on the evening of April 10 in Montenegro and the following evening in Sarajevo. He managed alone on April 13 to reach the Yugoslav General Staff, conveying the request of the Greek General Assembly to launch a Yugoslav offensive against the Italians in Albania.

Obviously this request was indulgently unreasonable as already there was not even a Yugoslav army to attack anywhere. Papathanasiadis returned to Athens only on the evening of April 14. By then the Germans had already attacked the non-permanently stationed Greco-British forces as early as 10 April. The order for the retreat of the Greek forces of Northern Epirus was given only on April 12.

It was already late. It is worth noting that the TSDM was already asking the General Assembly on April 8 to approve the retreat maneuver it had already planned. The Greek forces, after the destruction of the Central Macedonian Army Department and the retreat of the British, could not escape...

Of course, the ideal would be the deployment of the Greek and British forces in one line of defense and not in two (Beles – Nestos and Vermio – Olympos). This presupposed the temporary abandonment of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace and the transfer of the forces outside the forts to a line that could also cover the side of the Greek forces in Northern Epirus.

The abandonment of the Beles-Nestos location was not decided as Athens was waiting for Belgrade to clarify its position and most importantly, after the change of regime in Yugoslavia, it was waiting for the Yugoslavs to withstand enough time against the Germans and their allies.