The ancient Greeks, at least in Greater Greece, used in their army from time to time mercenaries from very distant places. Wars and mercenaries played an important role in the large-scale movement of people in the classical ancient Greek world of the Mediterranean. This was the conclusion of an international interdisciplinary team of geneticists and other scientists who analyzed the ancient DNA of people from the Greek colonies in Sicily.

The researchers, led by distinguished researcher David Reich of Harvard Medical School, made the relevant publication in the journal of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) of the USA. Greek scientists also participated in the study, including Reich's collaborator Joseph Lazaridis and Professor Ioannis Stamatogiannopoulos of the University of Washington. The scientists analyzed the genome of 54 human skeletons found, some with their weapons, in mass graves in the necropolises of Imera and its surroundings.

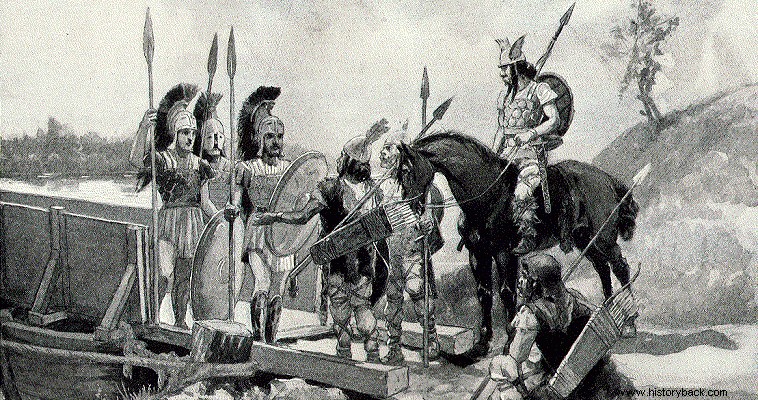

Among them were soldiers of the 5th BC. century aged 18-50 who had fought in the army of the Greek northern Sicilian colony of Imera (in the victorious for the Greeks decisive battle of 480 BC against the Carthaginians and their local allies), as well as civilian residents of the area and nearby settlements with native populations. Also, for comparison purposes, the genomes of 96 modern humans from Italy, mainland Greece and Crete were analyzed.

The analysis revealed the significant presence in the battle of Imera of mercenaries from northern and central Europe (even from the eastern Baltic near present-day Lithuania), the Steppes and the Caucasus, who fought on behalf of the Greeks . Scientists emphasize that reports of the presence of such distant mercenaries as early as the beginning of the 5th century BC. are absent from the historical texts and the issue has been underestimated by historians and archaeologists.

That is why they pointed out the need for the archaeological-historical research concerning the ancient Greek world to be gradually supplemented with more and more paleogenetic studies, as ancient DNA can shed new light on the past. The researchers concluded that armed conflicts functioned as an important mechanism of contact between very different cultures, facilitating osmosis between them and their assimilation into the ancient Greek world.

The researchers emphasize that "mercenaries were among the most distant travelers of the Greek world (perhaps rivaled only by slaves in this), bringing people of very different cultural and genetic backgrounds face to face."

They add that “in addition to the Greek colonists and the native peoples they encountered there, the mercenaries were part of the exchange of culture, ideas, and possibly genes that took place in the Greek cities of the first millennium BC. and in some cases they may have played an important role in securing Greek military victories".

As they say, the findings come to complement the picture that existed until now from the archaeological and historical evidence, supporting the idea that the mercenaries in the Greek armies of the classical period were an instrument of cultural change and a means of gene transfer in the wider Mediterranean area.

Although the wars are usually seen as a divisive force, in reality – according to the researchers – they were an additional catalyst of demographic change and cross-cultural contact, alongside trade and colonization migrations from mainland Greece to other places such as southern Italy and the Sicily.

Imera was a colony founded by Ionians and Dorians around 648 BC. and it was probably also inhabited by native Sicilians, Etruscans, etc. It was the westernmost Greek settlement in Northern Sicily and the site of two important battles (480 and 409 BC) between Greeks and Carthaginians.

In the second battle, which Imera fought without allies, the Carthaginians prevailed, destroying the city. The new study confirmed that the dead warriors of 409 BC. they all had very similar DNA and there was no evidence of mercenaries – which probably played a role in the defeat of the Greek colony.

Archaeologist Carrie Sulosky-Weaver of the University of Pittsburgh spoke of "exciting" findings in "Science" magazine, who emphasized "how it's impressive how much we can say about ancient episodes like this, with this kind of genetic evidence." On the same wavelength, bioarchaeologist Brittney Kyle of the University of Northern Colorado said that "this is the clearest case I've seen where bioarchaeology confirms what was written in the historical texts".

Historian Franco De Angelis of the Canadian University of British Columbia in Vancouver emphasized that "it is novel" the discovery that mercenaries traveled thousands of kilometers to fight on a Mediterranean island. "The idea that they came from so far away to fight will astonish people." On the other hand, archaeologist Gillian Shepherd of Australia's La Trobe University in Melbourne pointed out that "the Greeks were probably unwilling to credit mercenaries with their military successes".

APE-ME