Every March 5, a curious festival is celebrated in Zaragoza (Spain). It was the first of a secular and non-religious nature that the city had and that also has a bombastic name:Cincomarzada . But, what do Zaragozans celebrate every fifth day of March?

Ferdinand VII He died in September 1833, leaving a Spain anchored in absolutism and the Old Regime, but where liberal professionals, large fortunes, and what has been the social sector that will end up forming the upper bourgeoisie, have been clamoring for more than twenty years for a I change towards political liberalism, where the monarch and the aristocracy do not do and undo as they please and power passes to that increasingly wealthy bourgeoisie. It is the so-called National Sovereignty, that the State belongs to the people and not to the Crown, the concept of freedoms such as that of the press or the separation of powers that even today, two hundred years later, are still so much in vogue.

Fernando VII had great problems conceiving an heir, so in case of death it was his brother, Carlos María Isidro de Borbón who was first in the line of succession. But the ineffable Fernando finally managed to have a daughter in 1830, the future Isabel II, she becoming the heir to the throne. Carlos, a convinced absolutist like his brother, suddenly saw himself after almost twenty years as the relegated heir of the succession, and to make matters worse, relegated by a girl. For this reason, he alludes to the Salic law, which prevents women from reigning if there is a man, and begins to seek support that is also interested in preserving the absolutist model.

On the other hand, the wife of Fernando VII, María Cristina she, despite being deeply absolutist, sees the future succession of her daughter Isabel in danger, so she will seek the support of the liberals. Thus, in 1833 Ferdinand VII died and a few days later, his brother Carlos published the Abrantes Manifesto , for which he did not recognize his niece as queen and proclaimed himself king as Carlos V. Thus began the First Carlist War (1833-1840), which had great force in the current Euskadi, Navarra, the Aragonese and Castellón Maestrazgo and areas of Catalonia. But Carlism had its bases in the rural world, and never managed to have a great city that would serve as its capital.

Given these circumstances, on February 27, 1834, groups of civilians from Zaragoza met in the Arrabal and Las Tenerías and began to cause disturbances to provoke a general uprising in favor of the pretender to the throne, Carlos. These groups of civilians are joined in their support by Lieutenant-General Juan Penne-Villemur , Count of Penne-Villemur. However, the captain general of Aragon, General Ezpeleta , finds out what happened and after gathering an armed contingent and with the support of the population of Zaragoza, he forcibly represses the Carlist uprising, which flees towards Navarra after leaving several dead and finally joins the troops of the Carlist Tomás de Zumalacárregui .

Charge of Zumalacárregui – Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau (2009)

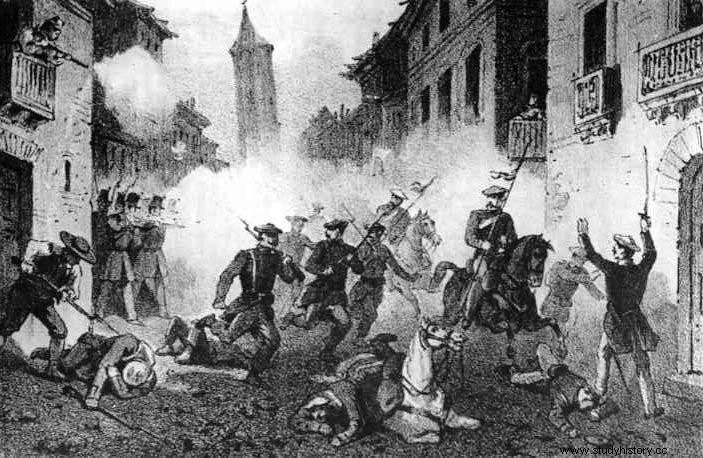

We arrived at March 5, 1838 . Zaragoza is a city that supports the Elizabethan liberal regime, but it is located right in the middle of the most important Carlist regions, so it was always the object of their desire. The Carlist soldier from Teruel Juan Cabañero He decides – other sources say that he was ordered by General Cabrera – to take Zaragoza by surprise and gathers 2,000 infantrymen and 300 cavalrymen. Cabañero uses the calm of the night to catch the Zaragoza garrison unawares - very scarce given that the bulk had gone to help Gandesa, which was under siege -, and at 3 in the morning his troops, helped by Carlist supporters, numerous in the neighborhood of Magdalena, they take the Puerta del Carmen, and after crossing the walls they begin to control the neighborhood of San Pablo and other gates of the city. The shots and the "long live Carlos" wake up the people of Zaragoza and their reaction is immediate. The militia begins to fight the attackers with the support of the entire population, women and men. The fight lasts all day and fierce clashes break out in various parts of the city such as the Plaza de San Francisco -now Plaza de España-, the market, the Coso, etc. The Carlists are attacked from all sides and finally, towards nightfall, Cabañero orders a retreat. General Cabrera reproached Cabañero for his failure and ended up removing him from the command of the Carlist army.

For the people of Zaragoza, this victory was a great feat, and since 1839 the City Council declared it a holiday, beginning the tradition. The people of Zaragoza begin to go that day to have a snack in the groves of Macanaz and on the banks of the Gállego river, the custom taking root very soon.

In 1843, the most conservative faction of the liberals achieved the government of the country and the Zaragoza City Council stopped declaring a holiday on March 5, although the residents did not want to lose this custom and continued to celebrate it on their own. It is again a holiday during the so-called Progressive Biennium (1854-1856) and during the First Republic (1873-1874), and finally continuously with the Bourbon Restoration since 1875. A street is even dedicated to such an event, the famous Calle Cinco de Marzo next to Paseo Independencia.

Zaragozans continued to celebrate the Cincomarzada for decades until the outbreak of the Civil War (1936-1939). In 1937, the Francoist City Council of Zaragoza decided to abolish the holiday and prohibit its celebration, since the Carlist Movement was part of the rebels against the Second Republic. Calle Cinco de Marzo itself changed its name, being renamed “Requeté Aragonese” –the requetés were the columns of Carlist soldiers-. This is how the festival remained throughout the dictatorship, until in 1979 the first democratic City Council of the city recovered the tradition and returned the name to the central Zaragoza street.

As a last point, talk about a little anecdote that the people of Zaragoza told. During the Carlist takeover of the city, Cabañero saw it so easy that he took the conquest for granted, so he forced a cafe to open at dawn and ordered a cup of hot chocolate. But just when he was going to drink it, the popular uprising of Zaragoza began against his troops, and Cabañero ran out of the cafe to direct his men without having drunk his mug. Years later, Cabañero joined the Elizabethan army and once took part in a military parade in Zaragoza. But the people of Zaragoza, displaying his characteristic sarcasm, yelled at him “Cabañero, your chocolate is getting cold!!”

Published in History of Aragon by Sergio Martínez Gil , graduated in History from the University of Zaragoza.