The other day we reported that Katsu Kaishu and his diplomatic mission to the US in 1860 was the first time a Japanese had ventured outside the confines of his country in more than two hundred years. But, strictly speaking, that is not entirely true. Katsu's was the first official and, let's say, intentional trip. But, before that, history has left us cases of Japanese castaways who, at the mercy of the currents, ended up with their bones in distant lands.

Today we are going to talk about the first of these involuntary travelers, whose odyssey through those seas of God has little to envy that of Ulysses himself. The year was 1832 and the draconian laws of the Tokugawa shogunate dictated that no Japanese subject could enter or leave the country, under penalty of death. All contact with the outside world was strictly limited to sporadic exchanges in the port of Nagasaki with Dutch and Chinese merchants, receiving a few hundred Korean embassies in the wind, and little else. For the Japanese of the time, the world beyond their islands simply did not exist.

Otokichi , a cabin boy barely 14 years old, was part of the crew of a small junk that made the route between Nagoya and Edo transporting rice and porcelain. One day in the fall, what should have been a routine trip of a couple of days became more complicated than expected. The ship, a humble skiff barely 15 meters long, ran into a fierce storm and ended up adrift in the middle of the Pacific. Left to their own devices, the sailors reached for the cargo of rice to survive but, over time, scurvy began to take its toll on the crew. Days, weeks, months passed... and soon only Otokichi and two companions, Iwakichi and Kyukichi , they were still alive.

Finally, after more than a year adrift, they sighted land. Little did they know that they were the first Japanese to set foot in the Americas; more specifically, on what is now the border between the US and Canada. But his misfortunes were far from over. As soon as they landed, they were captured (and enslaved) by the natives of the area, the makah Indians. , a tribe unfriendly to hospitality. The news of such picturesque captives soon reached the ears of the captain of the English garrison in the area, a certain McLoughlin , who became interested in the matter. McLoughlin, a man with a nose for business, deduced that the captives must be Chinese and thought that having them on hand could be a good asset for future commercial ventures. After all, England was beginning to have important interests in those parts. After several unsuccessful attempts at negotiation, he managed to free them and brought them with him to Vancouver.

Monument to the three castaways in Vancouver

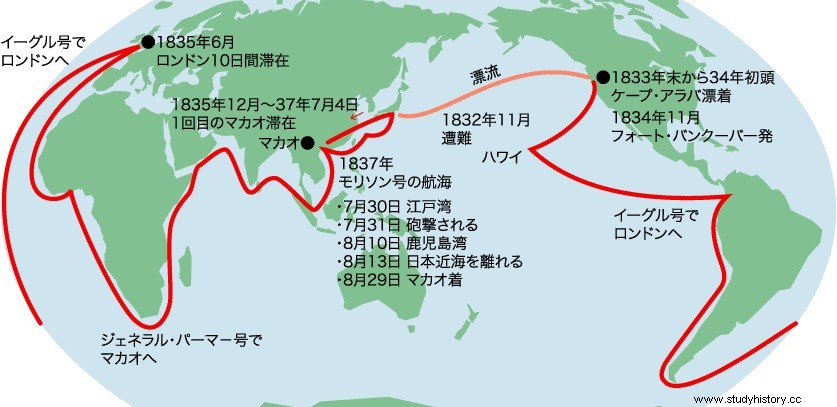

We can imagine that, with all this incident, Otokichi and company must have literally hallucinated in colors. They, simple village boys whose knowledge of the world did not go beyond the mountains of their village, suddenly found themselves with a universe that they did not even dream could exist. Both the Indians and their English liberators must have seemed like true Martians to them. The boys learned the language of Shakespeare under the tutelage of the local priest, and were soon ready to be introduced to society. In 1834 they set sail for London on a ship that would cross the Pacific again, passing through Hawaii and bordering Antarctica, until arriving in England seven months later.

Otokichi's Travels

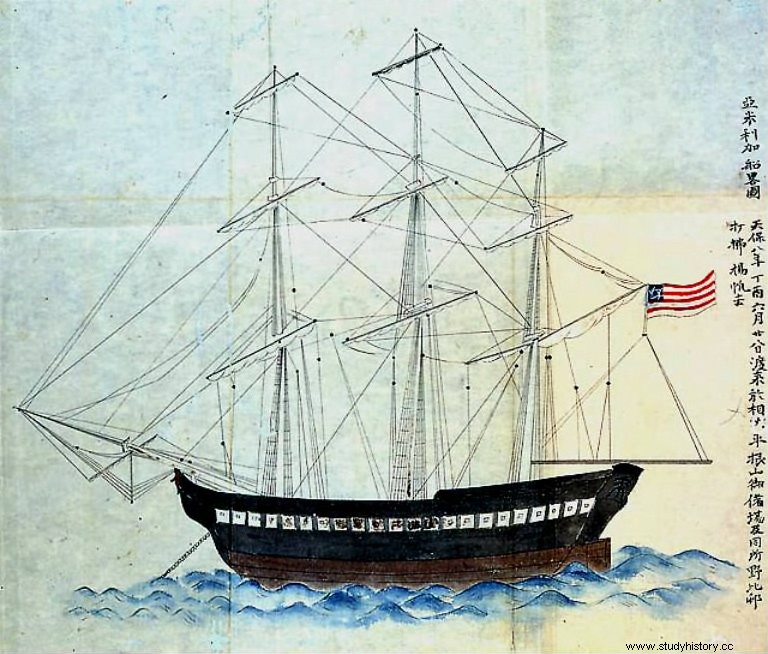

At just 16 years old, the wanderings of that little boy from a lost village in medieval Japan left the travels of Sinbad the sailor at the height of a country excursion. Otokichi was seeing more of the world than he could ever imagine, but nothing compared to what awaited him in London. There he was, in the middle of the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the world, destined to play a key role in the colonial diplomatic game. Unfortunately, His Gracious Majesty's government had other priorities. So, after spending some time touring the city, he ignored the three boys and sent them back the way they had come. Once again to sail the seas, now bound for Macao. Two years passed and Otokichi took advantage of the time to perfect his command of languages, coming to handle Chinese and English fluently. Not bad at all for a kid who, just five years before, was illiterate. At last, in 1837, he had the opportunity to return home. The Morrison , an American merchant, arrived at the port of Macao and brought in its holds a handful of Japanese shipwrecks that he had picked up near the Philippines. He intended to use his repatriation as an excuse to start trade with far-flung Japan, so when his captain learned of Otokichi and company, he wasted no time in adding them to the lot. But the isolationist decrees of the shogunate were still in full force, and Otokichi's compatriots were not very happy about the visit. The Morrison he was met with a clean cannonade in all the Japanese ports where he tried to drop anchor, so he had no choice but to turn back with a fresh wind. After five years of travel, the forced exile of those poor castaways had no sign of ending.

The Morrison

From this point on, it is not known what happened to his other two companions, Kyukichi and Iwakichi, but Otokichi had quite a few adventures ahead of him. Given the panorama, he decided that he had better forget about going home and look for a life elsewhere. He settled in Shanghai and, thanks to his polyglot skills, he made good money offering his services to English companies operating in the area. He married twice, eventually became a subject of the British Empire, and Christianized his name to James Matthew Ottoson , adaptation of the nickname by which he was called by his shipwreck companions, Oto-san . And, incidentally, he traveled half the world that he had yet to see enrolled in various merchant ships. According to the Japanese laws of the time, for all this Otokichi would have received several life sentences and a couple of death sentences, but nothing could matter less to him. By now, everyone in his homeland must have given him up for dead. No one expected his return anymore. There was nothing that tied him to his old homeland.

Otokichi

But fate takes many turns, and Otokichi would have the opportunity to set foot on Japanese soil again on several occasions. Only, this time, he would return with full honors, as the official interpreter of the English delegation. The tables had turned and now England was more than interested in following the path recently opened by the Americans and establishing trade relations with Japan. Otokichi was a key player in the negotiations of 1854, and the Japanese government, impressed, offered him to return home with a top job. Otokichi refused the offer. He had no intention of serving the same country that had gunned him down years ago. His homeland was now the South Seas, far from those ungrateful islands. Once his diplomatic work was completed, he retired to Singapore, where he lived comfortably until the end of his days with the income that the grateful English government paid him. The young boy Otokichi had long since disappeared. The man who had negotiated the treaties between England and Japan was the globetrotter Mr. Ottoson, the Odysseus of the South Pacific .

Collaboration of R. Ibarzabal

Sources:Native American in the Land of the Shogun:Ranald MacDonald and the Opening of Japan – Frederik L. Schodt