Fifth Sertorius born in 122 BC in Sabine lands, more specifically in the city of Nursia (today Norcia, in Italy). Nephew of Gaius Marius , soon excelled under his command, first in Numidia and then against the Cimbri and Teutons. As a reward for his bravery he was made a tribune in 97 BC. and sent to the always revolted Hispania, where he stood out four years later under the orders of the praetor Tito Didio by successfully conjuring an indigenous rebellion in Isturgi (Los Villares de Andújar, Jaen). In collusion with those of Cástulo (near Linares, Jaén), the inhabitants of that city massacred the Roman garrison while he slept, but Sertorius and a few lucky ones escaped in time. The Sabine gathered all the survivors outside the city and counterattacked, massacring the natives drunk with wine and success. Not content with this, he ordered his men to dress in the clothes of the fallen indigenous and appeared at night before the walls of Cástulo, the city that instigated that rebellion, entering it without inconvenience through his ruse and making a lesson of such caliber that he was awarded the grass crown as a reward for his daring.

In 90 B.C. he was appointed as quaestor in Cisalpine Gaul and later served as legate to his uncle Marius in the War of the Partners, the rebellion of the Italian allies. It was in one of those fights that he probably lost an eye. When his uncle entered into direct belligerence with Lucius Cornelius Sulla , Sertorius led one of the four legions with which Mario took control of Rome, shortly after making a lesson with the free troops of his uncle who had exceeded in the purge of him without taking disciplinary action with him.

Within the logical placement of related rulers in the most strategic provinces, Sertorius ended up being sent as praetor to Hispania Citerior in 83 BC, a position he held freely and promptly until Sulla took control of Rome and ordered his immediate removal. replacement by one of his trusted men, Gayo Valerio Flaco . The Sabine, aware of what his fate would be if he returned to Rome, chose to defy the dictator and declare himself in rebellion. Flaco entered Hispania using the betrayal of a slave of Livio Salinator, one of Sertorio's legates and in charge of controlling the Pyrenean passes, who was assassinated in his camp.

The Sabine could do nothing against a proconsular army of those dimensions in the open field, so in 81 B.C. he was forced to leave Hispania from the port of Cartago Nova, returning to Mauritania as a soldier of fortune along with three thousand faithful Romans who decided to accompany him on this new adventure. Plutarch tells us in his “Life of Sertorius ” several passages of his stay in the current north of Morocco, defeating and taking the city of Tingis (today Tangier) to the régulo Ascalis, relative of King Bocco and ally of Sila, fighting in single combat against legendary warriors and reaching in his expeditions until the Fortunate Islands (today the Canary Islands). Probably in these dark years of exile and legend he established his first contact with the Cilician pirates, ultimately true architects of the disaffection of the lower Roman aristocracy to his noble cause.

The policy of the optimate governors was not as condescending to the natives as theirs had been. Perhaps for this reason, a Lusitanian legation reached the Mauritanian coast in search of Sertorius at the beginning of 80 BC. The offer was tempting. A powerful coalition of tribes would be at his command if he decided to return to Hispania and confront Sulla's despotic rule. In late spring, Sertorius's personal army of two thousand Romans and seven hundred Maurian horsemen landed near present-day Tarifa, scoring swift and decisive victories against the governor of Hispania Ulterior and his fledgling legates.

Soon Sertorius had four thousand more men and seven hundred horsemen recruited from the Lusitanian tribes who saw in that Roman of noble character and innate qualities for war a kind of reincarnation of Viriatus and Hannibal, since he was as skilled and guerrilla as the first and as one-eyed and cunning like the second. Before winter, a great victory over the propraetor Lucio Fudidio near the Guadalquivir, which resulted in two thousand casualties among the enemy ranks, consolidated his leadership position and instigated the rebellion beyond the limits of Lusitania. Q>

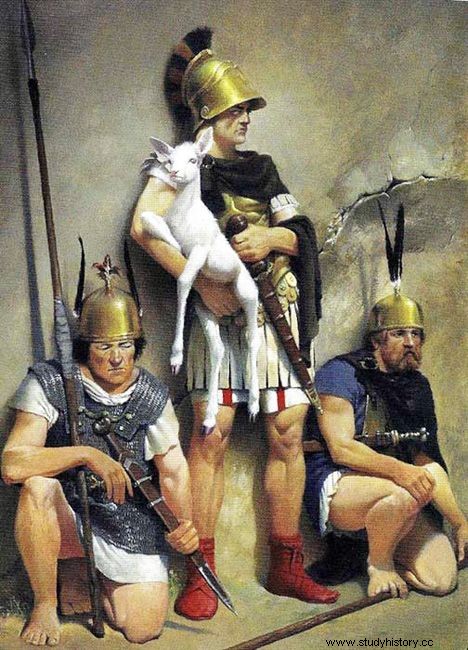

The following year Sila sent another of his staunchest acolytes as proconsul of Hispania Ulterior with the task of stopping that unexpected rebellion. He was Quinto Cecilio Metelo Pio , a plump, haughty aristocrat and lover of the excesses of the flesh in all its senses. Metellus mobilized nearly forty thousand men, a figure that was almost five times the forces of his rival. But Sertorio not only fought with soldiers:he did not take a higher title than proconsul in Hispania, thus maintaining the legality of his position, he created a Senate parallel to that of Rome in Osca (Huesca) with all the fugitives from Sila's purges, lowered taxes natives and provincial settlers, he was tolerant of all of them and promoted Roman citizenship among the indigenous oligarchies, even creating an Academy also in Osca to train the children of the Hispanic régulos in the Roman style. Also, around that time, a Lusitanian shepherd from the Mons Herminius He brought Sertorius a gift as strange as it was useful:a young white doe that was unusually docile, since they are not the cervid animals that we can consider as tameable.

The fact is that that fawn that behaved like a pet caused a stir among his men, as Sertorius told them in his public appearances that Ataecina or Diana, depending on whether their interlocutors were natives or Romans, spoke to him through her. Superstition is an easy way to manipulate the masses; religions applied it very well since ancient times...

Between 79 and 76 BC, Sertorius seized almost all of Hispania Citerior and the Lusitanian part of Ulterior, leaving the bulk of Metellus confined in Corduba and dominating the valley of the Betis (Guadalquivir) and part of the Anna (Guadiana). The entire Iberus (Ebro) valley supported the revolt, especially the Celtiberians to the detriment of the Basques, who remained on the sidelines, faithful to the government forces. In 77 BC Another disastrous adventurer escaped from the optimates purges arrived in Hispania, the second-rate aristocrat Marco Perpenna Vento , at the head of fifty-six cohorts who, as soon as they disembarked, deserted his commander to place themselves under the command of a man who was beginning to be a myth: Quintus Sertorius . With the indigenous levies trained as the legions and the new cohorts, the insurgent army reached the amount of seventy thousand well-equipped and motivated troops, a considerable force that invalidated Metellus as a solver of the Hispanic problem.

The merger of the two rebel armies caused the Senate to decide to send to Hispania the following year one of Sulla's most experienced pupils, Gneo Pompey , despite his youth already called "Great" because of his success in Africa and the social war with the dictator. Pompey was sent as proconsul at the head of a contingent similar to that of the rebel, made up of thirty thousand legionnaires and twenty thousand auxiliaries. His first punitive action after avoiding Perpenna between the Pyrenees and the Ebro was to go towards Lauro (today Liria), since this city had rebelled against the legate of Sertorius in Edetania, Gaius Herenius, and begged for help to lift the siege of the city. that the Sertorian forces had subdued her. The Sabine used his youthful momentum against him and set him in a deadly trap between two hills, tricking him through false reports into heading towards Lauro. When Pompey thought that he had Sertorius trapped between the walls of Lauro and his legions, the Sabine appeared at his rear and pinned him between Herenius' lines and his own. After a tense encirclement, in a skirmish near the besieged city, Laelius, one of Pompey's legates, lost nearly ten thousand men trying to rescue an ill-fated foraging sally. That setback, coupled with Pompey's immobility, forced the Edetans to surrender. The city was burned in retaliation for his sedition, while the young and humiliated optimate had to retire to winter in Gaul.

Sertorio's joy did not last long, since the year 75 B.C. it would mark the beginning of the end of his revolt. Ignoring his express orders to avoid all confrontation, the legacy of the Ulterior and his best legacy, Lucio Hirtuleyo, challenged Metellus in pitched combat who, after cunningly disinforming him, defeated him. The total destruction of the western rebel army, and the consequent death of Hirtuleyo himself, made it easier for Metellus to climb with his legions towards the common objective that the two government forces had set for themselves:Edetania.

In the spring, Pompey entered Hispania again with more reinforcements, heading directly for Edetania ready to right the wrongs of the previous campaign. His irruption into the heart of the revolt forced Sertorius to leave the camp and come to the aid of his legate Herenius. Pompey defeated Sertorio's lieutenant in front of the walls of Valentia (Valencia), causing more than ten thousand casualties to the insurgents, among which was that of the legate himself. After the battle, the rebel colony was taken by force and burned. It was a bloody fight, house by house and wall by wall.

Sertorius was late to save his comrades from Valentia, but not to challenge the young optimate to a new pitched battle that took place in front of Sucrone's permanent camp. With more than thirty thousand soldiers on each side, the battle of Sucrone was one of the bloodiest of Roman civil wars. Sertorius won on his flank, even endangering the life of Pompey himself, who was saved from death only because of the greed of the Mauro militiamen who served on the rebel side and who preferred to loot the expensive ornaments from the proconsul's horse rather than slaughter Pompey. his rider. On the other hand, Lucius Afranius, one of Pompey's most faithful legacies, won on the opposite flank, defeating Perpena and leaving the rebel camp at the mercy of the victors, who, instead of culminating in victory by persecuting the rebels, devoted themselves to their pillage. Thus, the mutual greed and lack of discipline caused that fierce battle to end in a draw with similar losses on both sides.

The next morning Sertorius was preparing to do battle again, but it was then that he received reports that Metellus' vanguards were only a few miles away; if he put up a fight and Pompey didn't attack, he could be caught between two mighty armies.

Without that old woman (Metellus), he would have sent that boy (Pompeius) to Rome after having beaten him up

This is what Sertorius sneered at his officers after listening to the messenger, mocking the mannered old glutton Metellus and the inexperienced Pompey, and then ordering stakes to be raised and his troops to be led to avoid direct clash with joint enemy forces that outnumbered him. ratio of three to one. A new pitched battle was fought a short time later at the foot of Saguntum (Sagunto), also with an uncertain result, since both parties came out badly. As winter was already showing its cold in the north, Sertorio demobilized his indigenous army and ordered all the parties to meet in Clunia (Coruña del Conde, Burgos), while Pompey was well received in Basque lands, where he settled down to winter in a new city on the indigenous Bengoda which the indigenous people called Pompaei-ilum ("the city of Pompey", today Pamplona).

The following two years there were no more pitched battles, since Metellus and Pompey, and then only Pompey, already as imperator de facto of Hispania, they changed their strategy, advancing like a pincer and subduing each rebellious city one by one. But it was not only this tactical change that changed the course of the war. Around this time Sertorius established a mutual aid treaty with one of the most undesirable individuals in the entire history of Rome, King Mithridates of Pontus , signed through the mediation of Cilician pirates who ruled the entire Mediterranean and who acted as authentic corsairs in the pay of the Kingdom of Pontus. In exchange for certain territorial concessions in Asia when Sertorius returned victorious to Rome, Mithridates would send gold and ships to Hispania to support the revolt. This unnatural alliance with a declared enemy of the Republic undermined many of the sympathies that Sertorius still had in the Senate of Rome, since no cause, no matter how good, justified collusion with a declared criminal for the Romans such as Mithridates.

As time passed and his area of influence was reduced, Sertorio's character mutated from calm and tolerance to anger and despotism, drinking without restraint and treating the indigenous people worse and worse as reports arrived that such a city or clan he deserted his cause under pressure from Pompey and his new friends:the Vascones. The point of no return occurred when the Sabine gave the order to kill all the boys of the Academy as a result of the defection of one of the oligarchs in whom he trusted the most and whose children were his "hostages".

The climate between the rebel leaders was rarefying for months until in the spring of 72 a.C. the group of the most intimate collaborators of him, headed by Marco Perpena, organized a plot to assassinate Sertorio in Perpena's own house on the outskirts of Osca. The excuse was to invite him to a banquet to celebrate a false victory, since his Lusitanian guard never left him alone and he refused to be seen in public. I will not narrate here the details of the conspiracy, they are very romantic, but according to what Plutarco told us, a certain Antonio was the first to stab him treacherously; behind him they pierced his toga Octavio Graecino, Aufidius, Fabius, Priscus and the host himself.

The new rebel leader lasted an assault on Pompey, who defeated him and captured him alive a short time later. Perpena tried to make a deal with the imperator offering Sertorius's private correspondence, letters of support involving many great men in Rome, as a bargaining chip for his life. Pompey did not hesitate to execute the traitor who had plotted the death of such a worthy rival, as well as burning the letters without opening them to prevent more Roman blood from flowing over said dispute.

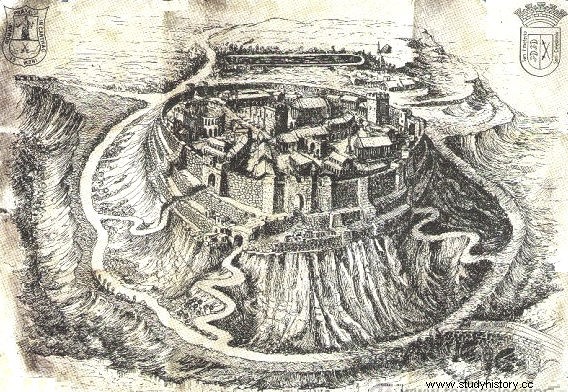

The revolt did not die with its leader. The devotio Iberian survived who provoked it, so cities loyal to Sertorius such as Tiermes (Termes), Uxama (Burgo de Osma, Soria), Clunia and Calagurris (Calahorra) continued to resist after the death of the Sabine, being the episode of Calagurris the creepiest and most brutal of them all. After months of siege and due to the lack of food, the Calagurritan Council accepted cannibalism rather than surrender. Such nefarious stubbornness and its implementation was still known in imperial times as the fames calagurritana , “the hunger of Calahorra”.

In the end, after exhausting the reserves of water, salt and slaves, children and women to sacrifice to feed the warriors, Calagurris unconditionally surrendered to Lucius Afranius, since Pompey had been required in Italy along with Crassus and Lucullus to definitively suffocate a slave revolt that was going on forever. The victorious legions of Hispania would now face a bizarre army led by a Thracian gladiator whose simple name caused panic:Spartacus.

Sertorius was another one of those Romans who suffered a damnatio memoriae . Cassius Dio and Appian vilified him, while Plutarch extolled his talent for guerrilla warfare. Without a doubt, he was a tactical genius of his time, capable of putting in check with very limited resources the most effective military machinery of his time. Perhaps he devoured himself and lost his studied composure as he realized that he could not win and that he could only aspire to be a new Pyrrhus, whose useless partial victories kept him further and further away from total victory.