Despite the fact that this activity is frequently attributed as an inheritance from the Etruscans, probably in syncretism with other Italic traditions, fundamentally from the Oscan-Campano-Lucana region, some authors such as A. Futrell think that the origin of the gladiatorship could be almost universal, being impossible to define a precise origin or place.

However, it is agreed that It was in the year 264 a. C. when the combats of gladiators appeared publicly in Rome. The combat of three pairs of gladiators organized by the brothers Marco and Tenth Brutus to honor their deceased father was held in the cattle market of Rome, the Foro Boario , long before the construction of the Colosseum . The gladiatorial games were held, during most of the republican period, in other places of the Urbs temporarily enabled for representations, such as the Forum Romanum , the cultural, political and religious heart of Rome, and only later were permanent amphitheaters built in the capital. During this stage, the gladiatorial fight would cease to be a practice linked to the funerary field to become a show that won the hearts of the people and, of course, the eyes of the richest men in Rome.

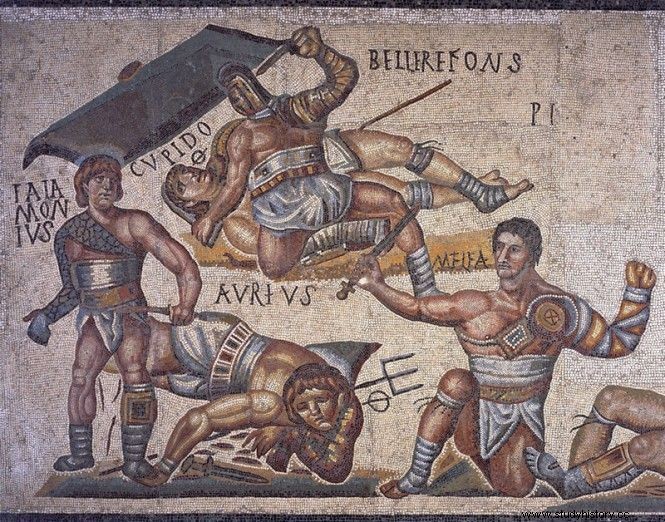

These combats served not only as entertainment but to educate the people in warrior and masculine values or as a sign of Rome's superiority over the enemy. The sentiments of the people oscillated between adoration and contempt for the gladiators. Contempt for being an activity considered by law infamous, dishonorable, insofar as it was typical of slaves, and this was marked both in society itself and in the skin of some gladiators, engraved by fire or with tattoos. But there was also the attraction to a profession that could border on glory and that represented virtus, bravery, discipline, constantia , pantyhose, love of glory and contempt for death itself. Even Pliny the Younger saw in these combatants the virtue of Rome:"...they inspire glory in wounds and contempt in death, because the love of fame and the desire for victory can be seen even in the body of slaves and criminals" ( PLIN. Pan. 33.). According to Alfonso Mañas, the power of the gladiators lay in the fact that even when they were dead they were admired by the people, a prize that even some emperors resisted.

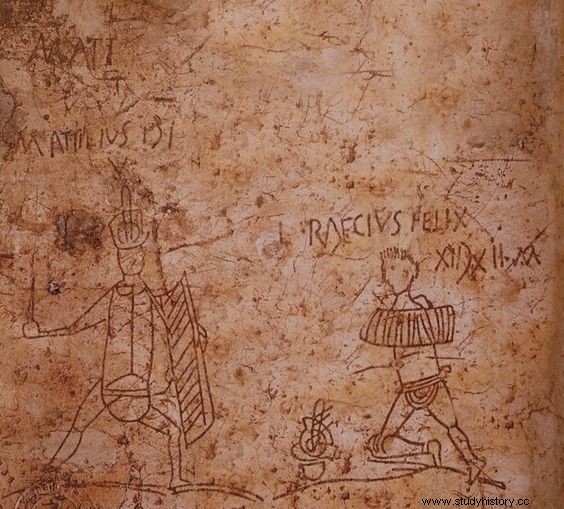

In this way, their popularity placed them as decoration for lanterns, glasses and other everyday objects, and as inspiration for the youngest:“It is the impression that among us children they take an interest in gladiators while they are still in the womb. Young people at home do not talk about anything else. But also at school…” (CAT. Dial. 29.3-4). Its value as political propaganda would reach its maximum splendor with the great games of Julius Caesar in 46 BC. C. in commemoration of the death of his daughter Julia from him. Venations, gladiatorial fights, elephant-riding warriors, and even an impromptu naval battle on the Field of Mars would cause such a high death toll that it would arouse Roman criticism. But what was the life of a gladiator really like? What was his training?

The arrival at the ludus

Most of the gladiators came from prisoners of war who were taken to the Roman camp after victory and forced upon arrival in Rome to participate in the triumphal parade as trophies. Later, they were selected and those in better physical condition were sold to lanistas private. The popularity of the gladiators was such that there were even scouts in the army in charge of selecting the best prisoners for the ludus imperial, assuring the best gladiators with respect to the private ones. There were great differences between the delinquent gladiators, condemned to the ludus that they lost their social status and were exposed to death and mutilation; the volunteers auctorati who presented themselves to achieve glory as the illustrious example of the Emperor Commodus or their own subsistence or, finally, the slaves, the fruit of enemy defeats.

As soon as you arrive at the ludus, the shot (“rookie”) took the oath auc-toramentum of the gladiators who assumed that he could be tied, burned, beaten or ironed to death. After an examination by a doctor (a specialist in gladiatorial training) and supervised by the lanista , those who did not meet the appropriate requirements were sent to the gregarii , the first to fall into the arena. But if the shot showed aptitude he was sent to the heavy weapons group or the light weapons group, depending on his qualifications. Since their arrival at the gladiator school, they were subjected to physical punishment that, however, must be taken into account from a context in which these methods were normal in activities that required a certain discipline. Sometimes, the rigidity of the superiors was so great that they provoked revolts, like the one that happened in the gladiator school of Capua led by Spartacus .

Despite this, those gladiators who earned it had a life in the ludus similar to that of the rest of the citizens, being able to leave this enclosure, form a family and, in the case of the most fortunate, have their own slaves. The ludus it would be an authentic tower of Babel, with multiple nationalities and its own social hierarchy parallel to that of Rome. The variety of languages would make the instructors also teach the Latin language or distribute their students depending on the dialects they spoke. Once assigned to their corresponding group, they began a hard training that turned them into combat professionals. This was done in the arena located in the center of the ludus and for it, wooden weapons were used, with only the defensive elements being made of iron or steel.

Training:the art of dying

Although funerary epigraphic information indicates that most gladiators did not accumulate more than twenty victories and usually died at an early age, many famous gladiators complained that games were rarely held throughout the year, at most two or three, and consequently spent most of their time idle or training in the ludus .

Gymnastic and physical training of gladiators in the ludus (exercitio ) was often directed by Greek instructors, accustomed to preparing their athletes for the Olympic Games since the 8th century BC. C. The amphitheaters and the ludus they had the best doctors in the empire, an investment of the lanista that guaranteed gladiators healthier and capable of fighting for more years. To this must be added the advice of the magistri , recently retired gladiators who taught the tactics and techniques of the trade. One of them consisted of the most effective way to perform sword blows, with the tip and not with the edges to cause greater damage to the opponent. However, the maxim of all gladiatorial combat was the balance between their opponents to keep the public's attention, with cuts with the blades being more effective than direct thrusts. To fight a duel, strength was an indispensable quality that used to be worked on by lifting both heavy and light weights. The former used to be used for lifting with the arms extended from the ground to the waist as if to carry them on the shoulders, and the latter were molded to perform arm exercises with them.

As for combat, he generally trained with weighted weapons, which weighed more than the weapons used in the arena, improving movement speed, reaction and resistance. The fighting exercises could be practiced either fighting each other or against a palus , stick stuck in the ground the diameter of a tree trunk against which full force sword blows were attacked even with the shield. The way of responding to the different attacks had a certain similarity to current fencing training, in which each attack hit has a specific counter-attack. Despite the risk they ran in the arena, the real danger of these fights was not so much in the wounds but in how the wounds caused to the opponent changed his attitude and the combat situation. There was nothing more dangerous than a mortally wounded rival. However, the art of gladiatorship was not only exposed to physical training, and since it is a sport practiced to be exhibited to an audience on which the life of the opponents often depended, the interpretive and dramatic abilities were basic. Rome had been characterized by turning community events into political spectacles and, as Dupont would say, Rome would go from a political spectacle to a spectacle as a place of politics. The creation of a catharsis with the public could be the difference between life and death, hence the importance of adopting nicknames that would give them popularity and highlight unusual qualities, which explains, for example, the prestige enjoyed by left-handed gladiators. (scaevae) .

The training also included teaching a certain interpretive level with which they were able to move or make the spectators fall in love and, especially, the six vestals who decided the verdict in the amphitheater. Graceful movements that did not require much effort were taught to gladiators to save energy while reproducing splendid combat. The bloody aesthetics of these shows hooked the public and turned the gladiator into a star, with a more expensive contract, for which publishers fought. But the preparation went beyond the movements, the gladiators were from the moment they were sold to the lanista under an exacerbated pressure before which a mental preparation was necessary.

As they were classified according to their abilities, they were assigned to different families They trained together. In these circumstances, it is not surprising that strong affective ties were forged, sometimes broken by confrontations in the arena. R. Auguet points out that the gladiators were prepared both to fight and to surrender to a death that could come at any moment. From the moment they entered the arena, the lives of these individuals remained in the hands of their lord and the public, something admired by the Roman people and that gave honor to their gladiatorial family. Cicero said that the people hated those gladiators who begged for their lives. However, resignation was not enough, a gladiator had to die hard, avoiding covering his face with his hands or struggling with his executioner. In fact, if necessary, he even had to direct the victor's sword against himself to finally and, as Cicero said, , “to die with the whole body”. Thus, behind the iron helmet, which barely revealed the face, the man behind the gladiator died with an ovation.

Bibliography and sources

GARRIDO MORENO, Javier. «The amphitheater:a dark image of Ancient Rome». Berceo Magazine no.149. 2005. Pp-153-178.

BASTIDAS MORNINGS, Alfonso. Munera Gladiatoria:origin of the mass entertainment sport. Doctoral Thesis University of Granada, 2011.

MUÑOZ SANTOS, M.ª Engracia. “Amphitheaters and ludi gladiatorii classical sources and Hispania as an example. An approximation». Saitabi. Magazine of the Faculty of Geography and History , 2012-13, p. 27-38.

MUÑOZ-SANTOS, M.ª Engracia. "The hard life of the gladiator outside the arena". Wake up Ferro Archeology and History nº14:Gladiators. pp. 48-53.

PASTOR MUÑOZ, Mauricio and PASTOR ANDRÉS, Héctor. Education and training in the ludus. University of Granada. 2013.

TEJA, Angela. «The sports buildings of Ancient Rome». History of Education, Interuniversity Magazine . University of Salamanca Editions. 1995-96, pp-47-59.

LIVED I CODINA, David. "Infamous and famous:the seduction of show business in Rome". Wake up Ferro Archeology and History #2:the underworld in Rome. Pp. 34-40.