Very little is known for certain about this momentous battle, since there is hardly any archaeological evidence and contemporary chronicles are fragmentary. The main primary source we have is Jordanes who, as a Gothic apologist for him, glorified the war actions of his fellow men on both sides and practically ignored the role played by the others. Therefore, any reconstruction attempt is a difficult task and, at times, a mere conjectural exercise:although we know that the battle took place in Champagne, between the current Châlons and Troyes, we do not know its exact location; we know which nations took up arms, but not in what number or proportion; and, finally, we don't even know what really happened in much of the battlefield.

Two specific locations have been postulated as the site of the Catalaunian Fields. One is Méry-sur-Seine, about 30 km. north of Troyes, simply because Méry could derive from Mauriacus, the alternative name Jordanes uses for the battle. The other is Pouan-les-Vallées, east of Méry, where the tomb of a wealthy 5th-century German warrior was found in 1842. Some 19th-century historians believed it could be the remains of the Visigoth king Theodoredo, who died in combat. , although most contemporary historians are skeptical about it.

Background

In the 5th century, Roman Gaul – present-day France – was going through a period of enormous instability. The borders had collapsed:Vandals, Alans, Franks, Alemanni, Visigoths, Sarmatians and Burgundians had occupied the country, either taking parts by force, or receiving land from Rome to settle in exchange for military benefits. The Gallo-Roman natives, severely mistreated and fiscally squeezed to the limit, chose either to flee in search of the protection of large landowners, or to revolt. The revolt of the Bagaudae – escaped slaves, serfs, and anyone who wanted to throw off the crushing yoke of taxation – had spawned an outlaw state in Armorica that, under the leadership of Tibato, even minted its own coins.

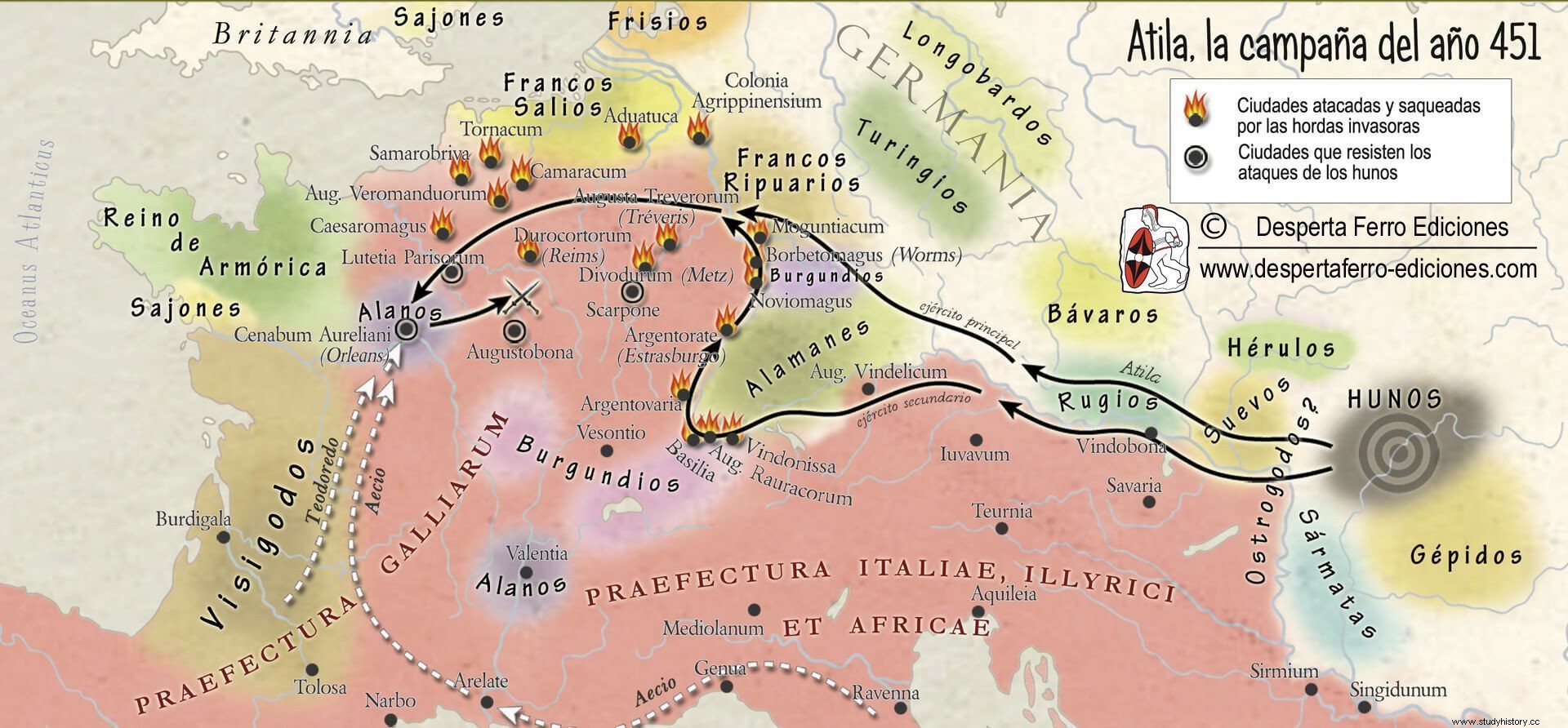

In the midst of this chaos, the patrician Flavius Aetius he seized power thanks to the support of the Huns, among whom he had lived as a hostage as a child. In the 20s of the 5th century he cemented his power in Gaul thanks to his Hun mercenaries and in 433 he defeated his main rival Count Boniface and seized the supreme military power in the West . Until 440 Aetius kept the Franks at bay, frustrated the siege of Arles by the Visigoths and seized Narbonne from them in exchange for recognition of their independence from Roman rule. In 437 he crushed the Burgundians with an army apparently composed exclusively of Huns, and two years later he captured Tibatus and put down the Bagaudae revolt. To help him stop possible advances by the Visigoths and keep the Bagaudae at bay, he established a colony of Alans near Orleans. Despite continual Bagaudean upheavals, Gaul enjoyed relative peace and stability during the 1540s. However, storm clouds were gathering in the east.

The Huns they had established a vast empire in present-day Hungary, stretching into the eastern steppes, subjugating or allying with the populations of the region. By then they had already had a considerable impact on Roman politics. Rua, king of the Huns –as well as friend and ally of Aetius–, died in 433. He was succeeded by his nephews Bleda and Attila and, later, the latter alone. Since then relations with Rome deteriorated rapidly. Attila forbade the Huns to serve as mercenaries for Rome – a blow to Aetius – and then launched two campaigns against the Eastern Empire (441-442 and 447) that devastated the Balkans and exacted a heavy annual tribute from Constantinople. However, in 450 his eyes fell on the West.

This change in attitude responds to a wide variety of causes, some quite trivial. First, the new Eastern Emperor, Marcian, took a stronger stance against the Huns than his predecessor. Furthermore, the Franks were at war with each other for leadership and the two rival princes asked Attila and Aetius for help respectively. On the other hand, the Vandals encouraged the Huns to attack the Visigoths, to which must be added that Attila sheltered an important Bagauda refugee; and, as if that were not enough, there was a dispute between the Huns and the Romans over certain looting. Eventually, Honoria, sister of the Western Emperor Valentinian III, was caught up in a court scandal and begged for Attila's help. This strange combination of events caused Attila to launch an attack against the West. As the contemporary Roman historian Priscus wrote:

The Hun army

There is no doubt that the army with which Attila crossed Germania heading for Gaul was very large for the time. Some maintain that it reached half a million men, while Jordanes affirms that the casualties of both sides in the Catalaunian Fields amounted to 165,000. However, these figures are implausible. Keeping an army fed and supplied on campaign was a logistical feat, even in terms of tens of thousands of men and horses, so it was rare for hosts of this era to exceed 20,000 men. Larger expeditions, like the one led by Julian against Persia a century earlier, required careful preparation and the pre-positioning of supplies and fodder. On the other hand, the actual number of warriors that could be raised in arms by any fifth-century barbarian tribe was far from what the frightened Roman chroniclers attested. The only reasonable figure we have is that of the Vandal people when they crossed into Africa in 429, whose total amounted to 80,000 souls. At best, this would mean 10,000-15,000 fighting men. It is possible that the Huns could count on more warriors, but logistics remained a barrier and it is highly unlikely that Attila would bring all his available strength with him at a time when relations with the Eastern Empire were still quite hostile. /P>

However, the Huns were not alone. According to Sidonius Apollinaris:

There is a good deal of poetic license in this description since many of the mentioned tribes had disappeared centuries ago and others are even fictitious. But it is clear that a large number of German subjects and allies marched alongside the Huns. We know of a group of Franks who, mired in a dynastic feud, had asked Attila for help, so they would probably be present. There were also some Burgundians, still living east of the Rhine, who may have been persuaded or forced to join the Hun army. It is almost certain that contingents of Skyri, Thuringians, and Rugii served alongside the Gepids under Ardaric, commander of the right wing at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields. Curiously, Sidonius does not mention the Ostrogoths, who possibly constituted the largest contingent of allies and formed the left wing in the battle led by the Valamiro brothers, Theodomiro and Vidimiro.

It is therefore reasonable to think that the strength of Attila's army could be counted in tens, not hundreds, of thousands of men. If we accept that the total number of warriors of the Vandal people would amount to 10,000-15,000 men, it is quite unlikely that even the largest of the contingents gathered in the Catalaunian Fields, such as the Huns or the Ostrogoths, numbered more than that. This was an invasion army, not a migrating people, so only fully trained warriors should have marched, leaving the rest behind to protect their homes. In the case of the smaller Germanic contingents, their strength was probably no more than a few thousand or even hundreds. That said, Attila's hosts could have mustered around 20,000-50,000 men in total, a relatively manageable number in terms of control and supplies.

The Huns were sacred horse archers . Armed with their powerful compound bows, they fired clouds of arrows at their enemies, avoiding contact with them until they had worn them down or broken the cohesion of their formation. Some would have been equipped as spearmen, capable of melee charging once the archers had softened up their opponents. The Germanic peoples were more in favor of shock tactics, whether on horseback – in the case of the Gepids and Ostrogoths – or on foot. Both Huns and Germans had lived in contact with the Romans for generations, and recently the Huns had inflicted crushing defeats on the Eastern Empire, so by 451 most of them would have Roman clothing and equipment, as well as their own weapons. .

The Roman-Visigothic Army

When Attila crossed the Rhine in the spring of 451, Aetius was in Italy. He immediately moved to Gaul, according to Sidonius Apollinaris alone with "a meager force of auxiliaries without legionnaires" (Carminia VIII). It is not clear why he was not accompanied by more troops from the Italian field army , perhaps the emperor did not want to leave the peninsula unguarded. On the other hand, a recent famine could have reduced the size and operational capacity of the army. However, it can be safely assumed that those auxiliaries who accompanied Aetius were not second-rate troops but palatine auxilia units. , capable of maintaining a solid battle line, as well as executing mobile operations. In status and training, they were superior to many of the ancient legions. It is likely that some cavalry units were part of this force, but while they might have been good troops, they would be very few in number, clearly insufficient to stop Attila.

Hasty diplomatic gropings had persuaded the Visigoth king Theodoredo to ally with the Romans instead of just defending his domains in southern Gaul. This must have been a difficult decision for the Goths, who had been enemies of Aetius in the previous decades, but it was clear that they were as much a target of Attila as the Romans themselves.

The Visigoths were the descendants of those men who had crushed the army of the East at Adrianopolis in the year 378 and that they had sacked Rome in 410. Settled in southern Gaul, they constituted a warrior aristocracy that dominated the native Gallo-Romans. After several generations having access to Roman weapons factories, the Visigoths must have been very well equipped compared to other Germanic peoples. Although originally most Visigoths fought on foot, by this time many warriors would have acquired horses, allowing them to fight on foot or mounted, their cavalry tactics being more flexible than those of their Ostrogothic cousins. Following Roman models, they could adopt both harassing tactics – harassing their opponent with a hail of javelins and avoiding contact – and shock tactics – charging with spears and swords – if their enemy seemed weakened. Defensively, the horsemen preferred to dismount and form a shield wall with the rest of the infantry to repel attacks.

Once reunited with the Visigoths, Aetius dedicated himself to gathering every last soldier available in France. According to Jordanes:

Interestingly, the Roman troops in Gaul are not mentioned at all. . Would there be any? According to the Notitia Dignitatum , a list of charges and units of the Western Empire at the beginning of the 5th century, the field army of the Magister Equitum Intra Gallias it was made up of 12 vexillationes cavalry (300 men each), 10 legions (1,000 men each), 15 palatine auxilia (500 men each) and 10 legions pseudocomitatensis (units formed with former border garrisons of unknown strength, probably between 500 and 1,000 men). On paper this army could have numbered 25,000 men. Also, there were significant contingents defending the Rhine border. What had happened to all of them?

The Rhine frontier had cracked after the migration of the Suevi, Vandals, and Alans in 406 and had been largely replaced by Frankish, Alemanni, and Burgundian settlements along the western bank of the river. During the 30s and 40s of the fifth century Aetius had relied on the Huns, rather than on the field army of Gaul, to keep Visigoths, Franks, Burgundians and Bagaudae at bay - it is highly probable that some Gallo-Roman soldiers had sympathies for them. the latter, if they did not directly join them. By 451, therefore, the Roman army in Gaul might have been reduced in both quantity and quality to a useless wreck. The ease with which Attila captured many of the Gallic towns – meeting little resistance, despite not having siege weapons – attests to the poor state of these troops. That said, it's safe to say that there were still some halfway decent troops around, which would have at least reinforced the Romans Aetius had brought from Italy.

The Franks that Jordanes mentions were the supporters of the prince who had chosen the Romans and not the Huns when asking for help, while when he speaks of Sarmatians he refers to the Alans. The Armoricans who may have been present must have been former Bagaudae, or perhaps recent refugees from Britain. The Burgundians settled in France were those who had survived the campaigns of Aetius. Although they had no more reason than the Visigoths to support him, his defeat had come at the hands of the Huns, and perhaps they had simply chosen the lesser of two evils. The Riparian were another branch of the Franks from across the Rhine who were possibly fleeing at Attila's advance, while the Saxons were those whom he had settled north of the Loire. We do not know who the bidders are, but it may be laeti , German or Sarmatian military settlers who were given land in exchange for military benefits. It is also very likely that the hosts of Aetius could be completed with private armies –bucelarii – of the powerful Gallic landowners. Perhaps these are the enigmatic olibrione s of Jordanes.

Unlike the Visigoths, these contingents were foederati , men from different backgrounds who had been granted land in exchange for serving in the army. Although they fought in their traditional ways, they were not technically independent allies, but rather an integral part of the Roman army of the Later Empire. They would have likely been supplied by Imperial weapons factories, so their appearance would not differ too much from regular Roman troops.

Possibly the allied army outnumbered Attila's, which, although distinguished by its aggressiveness in the past, opted for a more defensive strategy as the Roman-Visigothic hosts approached.

The Battle of the Catalaunian Fields

When Attila crossed the Rhine he met very little opposition. Some towns opened their doors to him without resistance, while others were raided and looted, such as Trier, Worms, Strasbourg, Metz and Reims. Attila's strategy was not to stop his advance, thus reducing his logistical problems and forcing the Western empire to plead for peace if it did not want to see Gaul devastated. While Aetius was gathering his forces, Sangibanus, King of the Alans Settled near Orleans, he promised to deliver the city to Attila. The Huns reached Orleans in early June 451 and surrounded it. However Sangibano was unable to keep his promise, or backed out at the last minute when news reached him that Aetius and Theodoredo were fast approaching. As soon as the Romans and Visigoths arrived, Attila lifted the siege and headed east toward the Champagne plains where his horsemen would have a greater advantage. Faced with this new situation, the Alans of Sangibano joined Aetius and the allied army began a relentless pursuit. According to Jordanes, a fierce rearguard action took place between Ardaric's Gepids and Aetius' vanguard Franks.

The one in the Catalaunian Fields was a battle that Attila never wanted to fight. His strategy was based on forcing the Western empire to sue for peace, but he had erred in considering that the ancient enmity between the Romans and the Visigoths would abort any potential alliance between them. Attila seemed to lack his usual confidence, but he still had to stand up, and his army followed him because he had always brought them victories and wealth. Giving up and retreating would have considerably undermined his position. Though the Champagne plains were ideal terrain for his village tactics, he hesitated before offering battle. According to Jordanes:

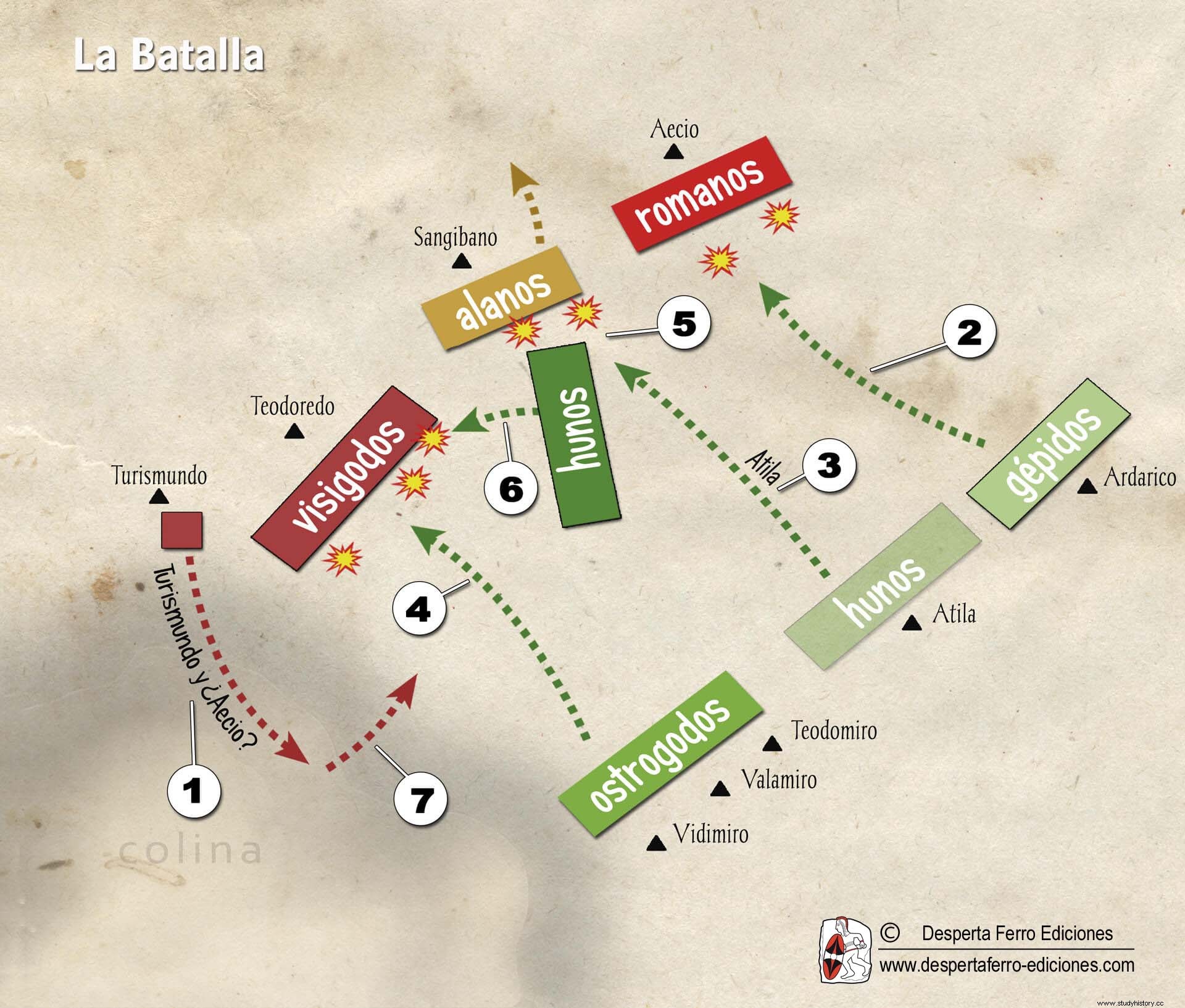

Aetius deployed the Visigoths on his right wing and Sangibano's unreliable Alans in the center, while he positioned himself with his "Roman" forces on the left wing. His double flanking strategy was to draw the Huns over to his center and drop on them from both sides. In this way he would prevent the highly mobile enemy light cavalry from outflanking his wings. Attila, apparently obliged, placed his Huns in the center, the Gepids to his right, facing the Romans, and the Ostrogoths to his left, facing the Visigoths. We do not know where the minor Germanic contingents were deployed, it is possible that they were divided between both wings or that they were concentrated on the right flank to reinforce the Gepids, who would be numerically inferior to the Ostrogoths.

Aetius began the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields by sending a contingent of Visigoths, commanded by Turismundo, the son of Theodoredo , to occupy the hill, which would presumably be on the extreme right of the allied army since the Goths were in charge of taking it.

This may lead us to believe that some of the best Roman troops also participated in this outflanking operation and that Aetius may even have led it personally, although it is unlikely that he would have relied on the rest of his motley forces to hold their ground without the authority of Aetius. Your presence. The scuffle over the hill, a forerunner to the actual battle, may have been what finally forced Attila to accept the fight. Details of what happened next are sketchy. In the center the Huns put the Alans to flight, then turned to support the Ostrogoths in their assault on the Visigoth position. Although many Visigoths could have been horsemen, it is very likely that, given their defensive strategy, they would have dismounted to join the solid shield wall of the infantry. In this way they would be less vulnerable to the arrows of the Huns. Although Jordanes does not recount what happened on the other flank, it stands to reason that the Gepids and other Germans failed to push the Romans back.

Although their position was compromised after the flight of the Alans, it seems that the Visigothic line withstood the attacks. "King Theodoredo, while reviewing his army to give them courage, fell from his horse and was trampled by his men... but some say that he was killed by an arrow shot by Andagis, who belonged to the Ostrogoth side." This eventuality could have ended in disaster had it not been for Turismundo, who along with his men had defended the hill. They "hurl themselves against the masses of the Huns and are about to kill Attila, but he realizes this and acts quickly, managing to escape with his men and hide in the enclosure of their camp that they had fenced off with chariots." (Jor. XL.209-210)

As night fell the combat became even more confused.

This seems to indicate that the Romans had prevailed on the left flank, so Aetius would have had a free hand to turn his attention to other points in the battle. It also seems to suggest that, after Theodored's death, the bulk of the Visigothic contingent would have retreated to his camp.

The next day no assault was made on the Hun camp, allowing Attila to withdraw unopposed. There are a number of hypotheses that try to explain this:perhaps the allies were exhausted, or it may be that their fragile alliance broke up once the immediate threat was nullified. It is also possible that Aetius was still more worried about the Visigoths than the Huns, so he preferred not to destroy them as he may still have a desire to count on them again as allies to counteract the growing Visigoth power.

Was the Catalaunian Fields then one of the decisive battles in European history? After her the Hunos continued being a threat for the interests of the Empire and invaded Italy the following year. If Aetius had been defeated, however, the Western Empire would have had to plead for a peace that would have made the Huns masters and lords of Gaul, and it is likely that much of the classical heritage that survived the fall of Rome would then have perished.

This Battle of the Catalaunian Fields article, by Simon MacDowall, was originally published in May 2010 as Desperta Ferro Antigua y Medieval #0 and It can be downloaded in pdf format at this link. Likewise, it was later included in the 2nd and subsequent editions of the Desperta Ferro Antigua y Medieval n.º1:The fall of Rome .

Basic bibliography

Jordanes:Origin and deeds of the Goths , trans. and ed. by José Mª Sánchez Martín, Chair, 2001, 146 pp.

Gordon, Colin Douglas:The Age of Attila , Ann Arbor Paperbacks, 1966.

Heather, Peter:The Fall of the Roman Empire , Critique, 2008, 712 pp.

Southern, P and Dixon, K.:The Roman Army of the Later Empire , Awake Ferro Editions, 2018, 320pp

Thompson, E.A, The Huns , Blackwell, 1996 (1st ed. 1948), 326 pp.

Simon MacDowall is a retired Canadian Army officer who has also held senior positions in NATO and the UK Ministry of Defence. He currently works as an independent researcher specializing in military history. The period of greatest interest to him is late Romanity, on which he has written several books and articles, including. His research tries to combine historical analysis with his own experience in the military and political fields.