In this text we do not try to carry out a detailed dissection of the “Roman cinema” , but to place the lens of the camera in the image of Rome, as a city and capital of an empire, through some films, and with the excuse of the triumphal parade, used as a vehicle to make that panoramic view of the city.

If the peplum stands out for something, it is because of its spectacular nature and colossalism, in a “the bigger, the better” , without historical rigor being a requirement that accompanies the visual representations of ancient cities such as Rome. It is worth appealing to the nuances:yes, Rome had over a million inhabitants at the time of Augustus, but the city that overflowed the Servian walls (later enlarged by the Aurelian walls of the 3rd century AD) occupied an area of approximately 20 square km. (see the fantastic project Digital Augustan Rome to give the reader an idea of the dimensions of the ancient city). Yes, Rome was (and is) a monumentally spectacular city, but it did not have the long avenues and perspectives that we usually see in many movies, but rather it was characterized by a chaotic urban development , with many narrow and irregular streets. Yes, there were large green areas and important complexes of palaces and recreational buildings (the Circus Maximus, the Colosseum, theaters, baths...), but the image that a Roman could see from the Janiculum (as today) must have been that of a congested city , packed with insulae and buildings of various heights, among which some temples and prominent buildings could stand out.

However, the cinema has lavished itself on showing the image of an extensive city , with generous main roads, colossal and immaculately white buildings (the "Hollyrome"), and great panoramic views that try to leave the spectator with his mouth open. Those who have been able to approach the Museo della Civiltà Romana and contemplate in situ the three-dimensional model of Rome at the beginning of the fourth century AD , they will have been able to verify that the image that the cinema has inoculated them hardly matches reality of a city that was constantly adapting to its environment. Why, however, does the cinema insist, however, on showing a Rome that, in some displays of megalomania, ends up being indistinguishable from the real one? The answer may have to be found in the Rome and greatness binomial; therefore, Rome had to be… great . How to show it then? With great buildings. How to get the viewer of a film to be in it? Through resources such as the triumphal parade.

The common reader also has a preconceived image of the triumphal parade , an honor that during the Republic was related to a military victory, a minimum number of dead enemies (five thousand, scrupulously counted), a commander who had been greeted as imperator by his troops, a determined development (parade of the victorious soldiers and chained enemy bosses) and a specific liturgy:the triumphator he walks the Via Sacra in a carriage, with his face painted red and in a hieratic pose; a person behind, a servant or a slave, constantly reminds him of his mortality (memento mori ); the parade usually ends with a delivery of offerings in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill. Cinema often presents the triumphal parade without the ritual complexity that accompanies it and with the intention of showing the Roman Forum filled to overflowing with enthusiastic citizens and delivered to the splendor of the moment (like today a soccer team that has managed to win a sports competition travels the streets of its city in a bus in a particular "triumphal parade" and surrounded by tens of thousands of supporters). What is that triumphal parade like and how is the Rome of the “Roman cinema” usually seen?

Quo Vadis (Mervyn LeRoy, 1951 ) begins with the victorious parade of Marco Vinicio (Robert Taylor) in Nero's Rome. We are located in an extra large version of the Roman Forum, surrounded by tall buildings (one of them, Nero's palace evokes the facade of the Vatican's St. Peter's Basilica). Vinicio crosses a high triumphal arch and enters the Forum. The ritual of the parade will be repeated often in other films:children and young people who drop flower petals as a carpet of honor, followed by a cohort of soldiers with banners and musicians who with martial fanfare herald the arrival of the honoree, mounted on a chariot or chariot, with the servant who says his phrase, until they pass in front of the emperor and later they go to deliver offerings in a temple. The image of the monumental center of Rome that the film conveys is imagined :it is not the Roman Forum that we know and, in later images of the city, it is not the "archaeologically" recognizable Rome either.

That Nero has in his palace a model of the Rome he yearns for (the same model in the Museo della Civiltà Romana) and that it will turn out to be the "real" one (for him the "designed one") does not stop being a peculiar play between fiction and reality (or planned reality in an invented space).

The development of the triumphal parade is repeated in Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959) , a film in which there are barely two sequences that take place in Rome; of both scenes we are interested in the triumphal parade of Quintus Arius after his victory against the Mediterranean pirates. Wyler's film does not have the intention of showing a Rome either, and if there is any doubt about this, all you have to do is see the panoramic view of Rome in perspective and from the top of the Capitol, at the beginning of the sequence of the triumphal parade; anyone who knows minimally the "narrowness" of the Roman Forum You can't help but wonder in what part of the city there is that very long avenue that seems to cross the Forum and reach the entrance stairway to the Palace of Tiberius.

Mounted on a chariot and preceded by hundreds of soldiers, musicians to the music of Miklós Rózsa (a triumphal fanfare symbolizing the "greatness" of Rome and evoking the subsequent parade of the charioteers in the chariot race), Quintus Arius (Jack Hawkins) and Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) go to receive the tribute of Tiberius (Ben Cross), seated on a throne under a large iron eagle located, to enhance the dimensions of this impossible space, at the top of the steps leading to the Capitol. Arius goes up the stairs (with Eisenstenian reminiscences) and receives from Tiberius an "emblem of victory" (a sceptre) as a symbol of his triumph... an exceptionality at that time, since from Augustus triumphal honors were exclusively monopolized by members of the family imperial.

We will find a version of the triumphal parade again in Cleopatra (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1963) , a film that has few sequences set in Rome:prior to the arrival of the Egyptian queen, the return (and at the same time triumphal parade) of Gaius Julius Caesar (Rex Harrison) is seen in a very brief scene, as well as a conversation between Marco Antonio (Richard Burton), Cicero (Michael Hordem) and a grown Octavio (Roddy McDowall) on the steps leading to the Senate, in a sample of some of the licenses or historical errors that accumulates the film:at that time (47 BC), Octavio was 16 years old, had not yet been adopted by Caesar and, above all, was not a senator. Later, the seat of the Senate will be the scene of debates in which Octavio manages to defeat Antonio's supporters; At the end of one of these meetings, in which Antony's will is made public, Octavian emerges "triumphant" from the Senate and, seizing a spear (according to the fetial rite), asks the Roman people, who pack the Forum, "Who are you?" where is the enemy? Where is Egypt? Show me the address!”… then spear Sosigenes (Hume Cronyn), Cleopatra's ambassador.

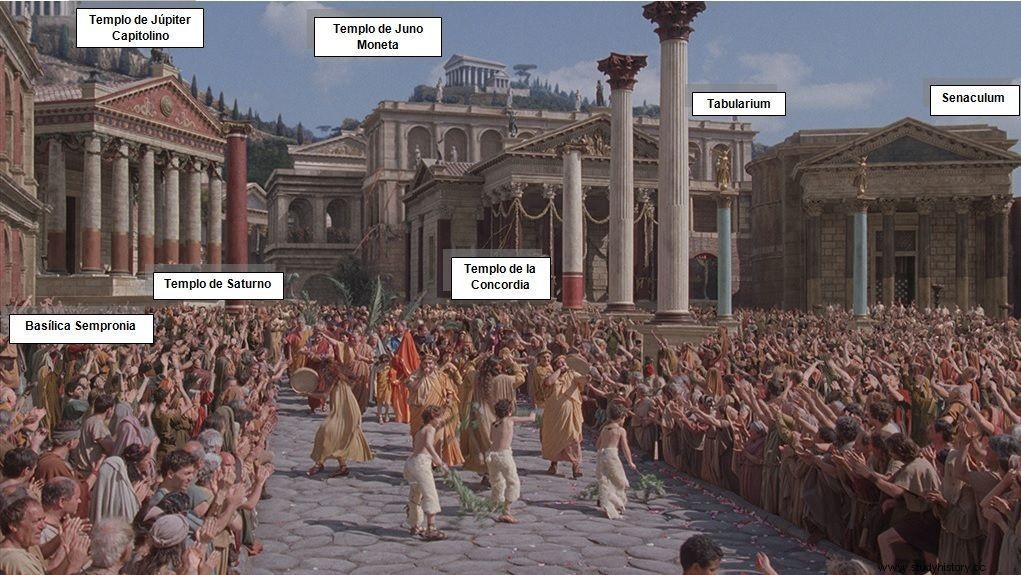

The sequence that interests us captures the essence of a triumphant parade... by a woman and also a foreigner. The entry of Cleopatra (Elizabeth Taylor) in Rome stands out for the magnificence of the sets and for a performance "exotic". The scene is historically impossible for foreign kings were forbidden to enter the pomerium or sacred precinct of the city; Cleopatra, like other foreign sovereigns (Yugurtha of Numidia, for example) had to settle for settling in a Caesar's villa on the outskirts of the city. The Roman Forum in Mankiewicz's film is similar to the real one in some buildings (the Sempronia basilica to one side, for example), but the triumphal arch that Cleopatra and Caesarion cross on top of a huge chariot in the shape of of sphinx did not exist at that time (it is a recreation of the Arch of Constantine, erected almost four centuries later). Caesar is seated in a curule chair on the opposite side of the forum, facing the Rostra and facing the grand staircase that leads to the Senate building. The crowd fills the central area of the forum, separated by a wide corridor, in which horse musicians, chariots, white and Ethiopian dancers perform the assigned part of the show before the arrival of the Egyptian queen. Behind Caesar, senators, mixed with some foreign guests such as Sosigenes and Apollodorus (Cesare Danova), contemplate the Egyptian parade with disgust, while on the other side their wives (some of them with hairstyles that would become fashionable two centuries later). late ) maintain an attitude. The Roman plebs watch the Egyptian parade with delight, admiring the variety of "exotic" items and all the while letting out gasps and applause; the common Roman, in fact, enjoyed parades and triumphal ovations, expected "souvenirs" and coins to be distributed among them, and valued the splendor and magnificence, sparing no expense, of a mass spectacle in the streets of the city. . Cleopatra's entry into Rome in this film would have filled those desires.

If the Rome of Cleopatra evokes in a certain way the historical one, that of Spartacus (Stanley Kubrick, 1960) it's unreal. There is no triumphal parade on this occasion, but there is an image of the Roman Forum.

Peter Ellenshaw, who had previously worked on Quo Vadis , he designed the Forum used in the film and which appears briefly in one sequence. Somehow we find ourselves in a large Forum, with the Capitoline Hill in the background, a terrace overlooking the square and some small temples around it.

Another sequence of the film begins with a panoramic view of the Forum, with the entrance to the Senate on the right and the Rostra opposite, while we observe another hill in the background, indistinguishable and crowned by a building in which colossal statues of what are known as supposed to be the great heroes of the Roman Republic. Commemorative columns dot the Forum, barely traveled (and not by crowds), just as inside the Senate, in this same sequence, the debate is followed by just a few dozen senators.

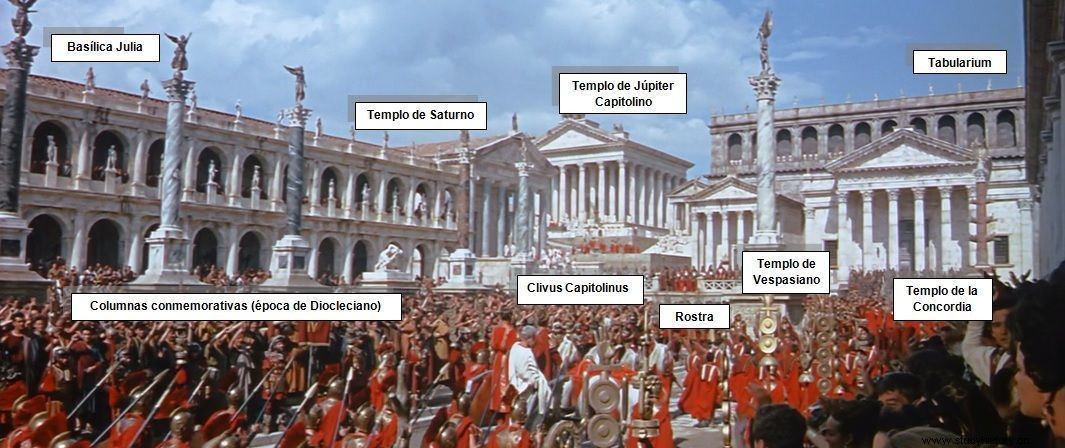

We will find a "faithful" version of the Roman Forum in The Fall of the Roman Empire (Anthony Mann, 1964) , which also includes a triumphal parade sequence. We can compare this scene with a very different one from Gladiator (Ridley Scott, 2000) , as both films basically share a similar plot in relation to Marcus Aurelius, Commodus and Lucilla. Let's start with the first of the two films:after being recognized as emperor by the legions located in Vindobona (Vienna), Commodus (Christopher Plummer) returns to Rome as a winner and makes a triumphal parade . Through the route of this parade, since Commodus arrives along the Via Sacra, crosses the Forum, climbs the Clivus Capitolinus and arrives at the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, where he will leave the laurel wreath as an offering to the deity, we observe from various angles a Roman Forum that is recognizable to us:in the next frame we have pointed out some of the buildings that existed around the year 180 d. C.

Preceded by soldiers on horseback, musicians, servants bearing offerings, Commodus appears, mounted on a chariot (and with the servant who remembers his mortality behind him), but without grasping the reins; he crosses the (reconstructed) arch of Augustus, next to which is distinguished the (circular) temple of Vesta, adjacent in turn to the temple of Castor and Pollux; in the background, in one of the few anachronisms that has the set of the historical center of the city that appears in the film, we observe an aqueduct that would be of later time. The entourage runs along the side of the Forum where the Julia basilica is located (in front of which some commemorative columns are placed that are also a later anachronism) and Commodus greets his sister Lucila (Sophia Loren), married to the king of Armenia (Omar Sharif). The parade turns to the other side of the Forum to show the porticoes of the Emilia basilica and head towards the Rostra and the temples of Vespasian and Concordia, which it surrounds, and up the Clivus Capitolinus. Halfway through, Commodus greets the crowd and allows us to see another view of the Forum from the Capitoline Hill. He once he arrives at the entrance of the temple and gets off the chariot, between impassive and bored, the sentence of the servant, and enters the building. The tour has allowed us to observe the most careful reconstruction of the heart of ancient Rome until then shown in the cinema. Anachronisms aside, the only defect of this set of decorations is the snowy white of the marble of the buildings, scrupulously elegant.

Preceded by soldiers on horseback, musicians, servants bearing offerings, Commodus appears, mounted on a chariot (and with the servant who remembers his mortality behind him), but without grasping the reins; he crosses the (reconstructed) arch of Augustus, next to which is distinguished the (circular) temple of Vesta, adjacent in turn to the temple of Castor and Pollux; in the background, in one of the few anachronisms that has the set of the historical center of the city that appears in the film, we observe an aqueduct that would be of later time. The entourage runs along the side of the Forum where the Julia basilica is located (in front of which some commemorative columns are placed that are also a later anachronism) and Commodus greets his sister Lucila (Sophia Loren), married to the king of Armenia (Omar Sharif). The parade turns to the other side of the Forum to show the porticoes of the Emilia basilica and head towards the Rostra and the temples of Vespasian and Concordia, which it surrounds, and up the Clivus Capitolinus. Halfway through, Commodus greets the crowd and allows us to see another view of the Forum from the Capitoline Hill. He once he arrives at the entrance of the temple and gets off the chariot, between impassive and bored, the sentence of the servant, and enters the building. The tour has allowed us to observe the most careful reconstruction of the heart of ancient Rome until then shown in the cinema. Anachronisms aside, the only defect of this set of decorations is the snowy white of the marble of the buildings, scrupulously elegant.

In Gladiator we find the opposite:an invented Rome , megalomaniac and evoking fascist imagery. In the triumphal parade from Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix) we observe clear reminiscences of Leni Riefenstahl (and her documentary The Triumph of the Will 1935) and the architecture of Albert Speer (Germania, the projected Nazi capital). The sequence begins with the appearance, from the skies, of Rome, a reconstruction of the model of the Museo della Civiltà Romana that now "comes to life".

A huge eagle on top of a building and over the initials SPQR gives way to a panorama of a wide avenue, with the Colosseum behind, with colossal equestrian statues and in front of which the crowds look like ants. Commodus, riding a chariot (which he doesn't drive), carries his sister Lucila (Connie Nielsen) by his side (one of the many anachronisms what's in this movie). The chariot enters an immense square (reminiscent of St. Peter's in the Vatican), with the Colosseum as a constant reminder of which is the most outstanding building; he presides over the scene, on top of the Senate building, a delegation of senators.

Commodus gets off the chariot and accompanied by Lucila goes up the stairs, in turn evoking an image of Hitler at an NSDAP congress in Nuremberg, shot by Riefenstahl in The Triumph of the Will , and receives a floral offering. The symbolism it is probably highly exaggerated… but effective:Commodus is a dangerous emperor; the crowds, ordered as in the Nazi congresses, only await the panem et circenses and they are hardly shapeless masses.

The television series Rome (HBO-BBC-RAI, 2005-2007) one of its virtues is to show a "realistic" image of Rome:a chaotic, dirty city, without a clear "urban plan", with clear distinctions between the domi of the senatorial elite and Caesar's family, and the insulae and small houses of the Aventine.

The image of the historic center of the city also shows poorly paved streets, public buildings that are not as "clean" as Hollywood movies have usually presented, more brick and terracotta than marble, and earthy colors in porticoes and balustrades, but it is perceived a documentation on the Rome of the years 40-30 a. C. The tenth episode of the first season features Caesar's triumphal parade for his campaigns in Gaul and with some of the elements of pomp triumphant:red paint on the face of the triumphator , spolia , captured enemy chief (Vercingetorix) and later executed, tour through the streets, popular acclamation, soldiers and musicians, etc. The route of the triumphal procession shows the historical center of the city, recognizable in some of its buildings. A clearer image of the Roman Forum appears in the last episode of the second season, which also uses the device of the triumphal parade to show the city, in this case the Octavian triumph , and in which we can admire some of the buildings of the Roman Forum (with a certain image wash).

This tour of cinematographic Rome (and television), which leaves other recreations in the pipeline –such as, for example, Caesar's triumphal parade in Julius Caesar (Uli Edel, 2002; from minute 16:18)–, could not end without those "timeless or modern" Romes transferred to the present, as in Titus (Julie Taymor, 1999) , based on Titus Andronicus of Shakespeare, and in which the complex built by Benito Mussolini at the Espossizione Universale di Roma (EUR) becomes the setting for the plot, and with particular "triumphal parades" by Saturnino (Alan Cumming) and Bassiano (James Frain) in the streets of the modern city of Rome; in Rome also contemporary (and located in an Eastern European country) of Coriolanus (Ralph Fiennes, 2011); or in the Rome recreated in the cells, corridors and courtyards of a prison on the outskirts of the Roman capital in the particular version of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar in Caesar must die (Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, 2012) , with real prisoners as actors.

One way or another, Rome (real, imagined or invented) remains a city of cinema.