"Athens is the only place," the proud statesman Pericles put it in a nutshell, "where an apolitical person is not considered a quiet citizen, but a bad citizen."

In the beginning there was an uprising

Between 508 and 322 BC the Athenians for the first time no longer obeyed a king, no noble caste, no tyrant, but only themselves - and with such consistency and passion that this period in the history of democracy is still considered a stroke of luck. However:women and slaves are left out.

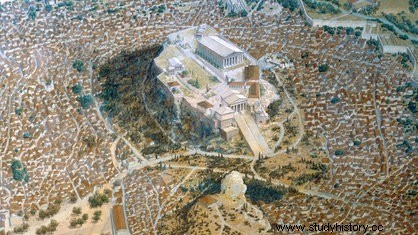

We write the year 508 BC. Isagoras, the highest official in Athens and a favorite of the nobility, has entrenched himself on the castle hill – together with Cleomenes, the king of Sparta, who has rushed to his aid.

Shouts of disapproval penetrate the thick walls:Thousands of Athenians have spontaneously gathered on the slopes of the Acropolis and vent their anger.

Although the Spartan Cleomenes had only freed the city from tyranny two years previously, the long-established noble families are now to regain power with his support.

But the people finally want to take their fate into their own hands. After three days, the besieged must admit defeat and flee the city.

How is it that in Greek antiquity Athens of all people took the path to democracy - unlike Sparta, for example, whose citizens came to terms with their political powerlessness?

The answer is to be found in the fields surrounding the city. As early as the 6th century BC, the population was growing so rapidly that the farms of each individual farmer were becoming smaller and smaller.

Many have to borrow money from rich nobles, work as bonded laborers or are sold into slavery by their creditors. Riots break out – until the Athenian Solon is invoked as an arbitrator in 594 BC.

For the first time, he included the ordinary people in power:the people's assembly, the meeting of all Athenians, and the people's court were open to everyone from then on. Only political offices are still tied to a minimum income. Achievements that the tyrant Peisistratos quickly cashes in again 50 years later - but a start has been made.

The Areopagus:From this hill the nobility ruled

Cleisthenes reforms the political system

Another 50 years later, after the successful siege of the castle hill, the hour of democracy finally came. This time the official Cleisthenes poured the protests of the Athenians into concrete reform projects - and has since been regarded as the founder of Athenian democracy.

Around the year 507 BC, he created a new body, the "Council of 500":In the future, it was to prepare the decisions of the people's assembly, making it an effective body for the first time.

And even more important:The council members are not elected, but determined by lot - every year anew. It's the same with the people's court, with the highest judges, called archons, and with the officials:They are all drawn by lot.

This ensures that responsibility does not remain in the hands of a few as it used to be.

This is where the roots of what "The Greens" were to try more than two millennia later:The so-called rotation principle, with which, at least in theory, other party members should always come to power.

Where once the people met, today only ruins remain

The bourgeois self-confidence is growing

In the decades that followed, the Athenians successfully filled the newly created institutions with life. With the naval battle of Salamis (480 BC), the Persian wars ended victoriously for the city-state - not least thanks to the superior Athenian fleet and its oarsmen.

Mostly poor people, they are now taking their place in politics with increasing self-confidence. And the new face of the city encourages them in this.

If you enter Athens from the southwest, for example, the Pnyx on the edge of the market square immediately catches your eye. In this stately building, the popular assemblies are held 40 times a year.

Any male citizen over the age of 18 can participate - and it's correspondingly lively. According to most lore, everyone, regardless of age or background, actually has a chance to intervene in the debate.

Because in order to break the dominance of particularly eloquent speakers, you are only allowed to speak once per topic. "Everyone stands up and joins in deliberation", writes Plato in the "Protagoras":"in the same way carpenter, blacksmith, shoemaker, merchant, shipowner; rich and poor; of high and low descent."

Acropolis, Agora and Pnyx

Of Voices and Shards

There are also no limits to the content of the discussions. The people's assembly argues about the upgrading of the fleet as well as about the price of the public theater performances or the construction of new places of worship on the Acropolis. In addition, the work of the political incumbents is checked.

If there is evidence of abuse of power or well-founded fear of a coup, the suspect can be banned from Athens for ten years by vote. The voters have to scratch his name on a piece of broken glass - hence the term "ostracism" which has become proverbial.

Since then, it has been repeatedly asserted that the Athenian democracy sometimes gets out of hand populistically precisely because of this instrument. Admittedly, the laws alone impose narrow limits on the Athenians.

For example, a ostracism court can only be held once a year, and only if at least 6,000 voters - about a fifth of all full citizens - are present.

In addition, the people's assembly itself is often very level-headed and revises decisions that have been made in a hurry:quite a few exiles have apparently been brought back to the city after a short time

The general Aristeides was banished with these shards

The Dark Secret of Athenian Prosperity

Athens' direct democracy is vulnerable for a completely different reason:Depending on the estimate, only between 15 and 20 percent of the population are even entitled to participate in political life.

Women are confined to the home. The numerous slaves are mostly treated with respect, some even manage to buy their freedom - they are not allowed to take part in the people's assembly.

Athens is at least as strict with the numerous immigrants who live in the city. They are not allowed to own property, they have to pay a poll tax, and only a few of them obtain full citizenship - even though economic life could not do without them.

To this day, there is a heated debate in antiquity research as to whether the Athenians would have been able to carry out their comparatively time-consuming political commitment at all without the work of slaves and women:after all, they kept everyday life going while the men who were entitled to vote happily discussed things on the market square.

A counter-argument is the diets that Pericles, one of the most important statesmen in Athens, introduced:He paid a fee to every participant in the popular assembly.

This means that nobody is really dependent on others to compensate for their loss of earnings. Nevertheless, this question shows the blind spot of the Athenian love of freedom.

Pericles introduced diets in Athens

An end and a beginning

What finally heralds the end of Athenian democracy is quickly told. Athens survived the Peloponnesian War against Sparta (431 to 404 BC) and held out even as Alexander the Great steadily expanded his power from Macedonia.

However, the proud democrats then had to admit defeat to the onslaught of Alexander's successor Antipatros.

After several defeats of both the Athenian fleet and the land forces, Antipater occupied the Athens port of Piraeus in 322 BC and from there established an oligarchy - a rule of the wealthy that ended more than a century and a half of popular rule.

However, the effectiveness of Athenian democracy can hardly be overestimated. Many modern democratic movements would later refer to them.

And one thing is certain anyway:with the temples of the Acropolis built during this time, with philosophers such as Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, with the tragedies of Sophocles and the comedies of Aristophanes, this short and lively time has shaped our image of ancient Greece to this day.

Aristotle and his disciples