(1) high altar of Pergamon , Berlin

Born January 4, 1839 in Steele, the young Carl will undertake a classical school career. From what little we know of those years, he still had a good knowledge of history, a light style in Latin, and showed great skill in mathematics.

Thereafter, he began to study engineering at the “Berliner Bauakademie” (Academy of Architecture in Berlin) in 1860. In the autumn of the following year, he stopped his studies for health reasons and followed the call of his older brother Franz, a civil engineer, on the island of Samos in the Ottoman Empire. There he promises Karl work and archaeological activities.

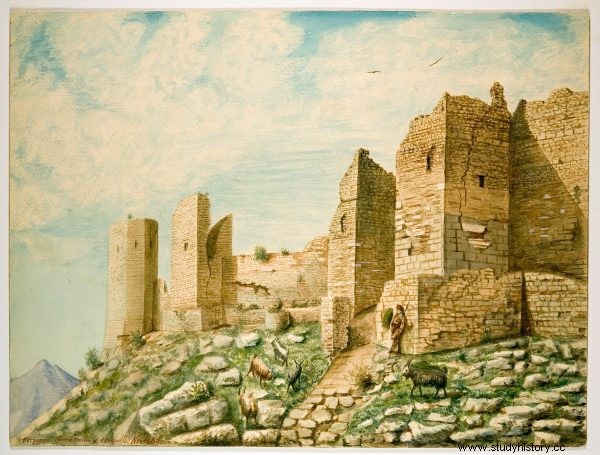

In the hope of relieving, if not curing, tuberculosis thanks to the healthier climate of the Mediterranean region, he landed on the island of Samos on November 15, 1861. He participated, among other things, in the excavations of the Heraion and ancient palace complexes. He gradually becomes fond of ancient relics. In fact, Carl therefore remained in the Ottoman Empire and continued to work as a civil engineer. In 1864, he went to Palestine on behalf of the Ottoman government to visit it and make an accurate map of the country. In preparation for further excavations, he visited what is now called ancient Pergamum in the winter of 1864-65.

At the well-known, but ramshacklely excavated historic site, he first uses his influence to prevent the destruction of the partially exposed marble ruins in the lime kilns as much as possible. In the vagaries of a reserved and, so to speak, ghostly diplomacy, he did not obtain support from Berlin for a proper search.

In Asia Minor, Carl and his brother Franz managed road construction from 1867 to 1873. He later came into contact with the cartographer Heinrich Kiepert as well as the little-known Ernst Curtius, the head of the Berlin antiquities collection. Popular but little in demand, why such a lack of regard for Pergamon? An unstable geopolitical situation, but not only:the excavations planned in Pergamon were not given priority because the archaeologist Curtius turned above all to the excavations of Olympia.

(2) Carl Humann (left) and Richard Bohn in front of the halls of the Sanctuary of Athena with the statues of Athena and Hera.

Why was Pergamon forgotten and lost?

We must go back to the prosperous days of antiquity and to the very origin of the word Pergamum (purgos ) which designates a fortified place, a fortress in short. It is in the Anabasis of Xenophon that we find the very first mention of the city, in 399 BC. In the text, it was about the reception given to the Greek mercenaries returning from Persia by Pergamum. After the victory of Alexander the Great in 344 BC, the city became independent. Propelled into the capital of an important Hellenistic kingdom in the 2nd and 2nd centuries BC, it will shine with a thousand lights under the Attalid dynasty.

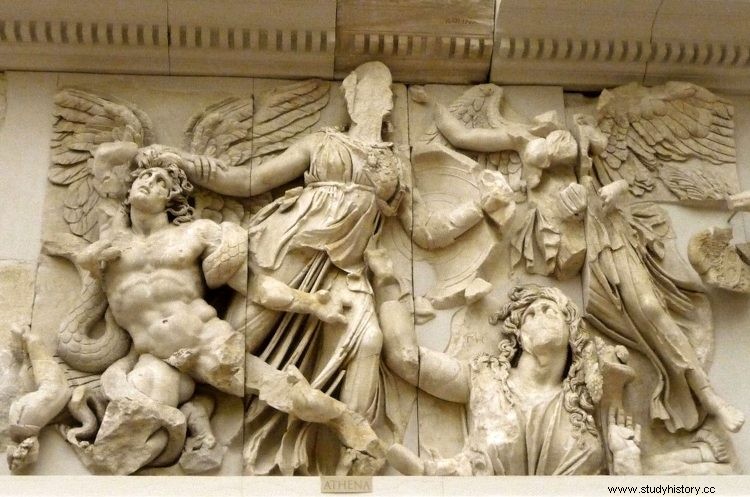

The vicissitudes of time got the better of its power:in 133 BC, it was bequeathed to the Romans by Attalus III. It eventually lost its appeal with the introduction of Christianity. The heroon, the royal palaces, the arsenal, the water supply, the temple of Dionysos, the sanctuary of Athena or the altar of Zeus, everything was gradually forgotten. But the worst was yet to come, in the tinsel of a golden age ending:the destruction of the city by the Arabs on their way to Constantinople in 716 marked a striking decline, described by contemporaries as a divine retribution. The famous Pergamon altar, where the gigantomachy sat in majesty, was demolished along with other buildings. The reason was stupidly prosaic, it was necessary to erect new fortifications in a hurry to guard against unpredictable incursions of the attackers. Thus, many marble sculptures were torn out and reused in this new rampart. Paradox of history:this rampage for survival was to protect them from further destruction, protected and thus buried, for centuries...

(3) Pergamon, Turkish wall of the Acropolis, watercolor by Carl Humann (1888).

Key date of its rediscovery

Carl traveled to Pergamon in 1865, there he worked on road construction projects for the Ottoman Empire. After having observed, on the site of ancient Pergamon, workers who exploited the marble of the ruins to make lime, he ended up convincing the Turkish authorities to put an end to the destruction of the monuments for a moment and quickly contacted the museums. of Berlin for the financing of the excavations.

Nothing was decided yet at that time. A feat of communicating vessels, it was only after the intervention of Alexander Conze and Richard Schône that the Ministry of Culture released official funds and the main remains were unearthed in three major excavation phases between 9 September 1878 and December 15, 1886.

The site was immense, the challenge all being, but one of the main objectives was to recover the frieze of the altar from the Byzantine ruins and to locate the original foundations of the altar itself. According to Ottoman law, archaeological finds had to be shared between the excavators and the Ottoman Empire.

After a series of negotiations, the Germans succeeded in obtaining possession of the sculptures of the Pergamon Altar for the museums of Berlin. With the assistance of a committee of museum experts and renowned sculptors, the Italian restorers Antonio Freres and Themistocle Possenti reassembled with immense difficulty the panels of the main frieze from a giant puzzle made up of thousands of fragments. .

The reconstruction was greatly aided by the research of archaeologist Otto Puchstein, who had discovered that inscriptions of the names of gods appeared above the figures represented on the panels of the frieze. Thus, thanks to the assembly marks, it was possible to determine the exact succession of the panels and the order of the scenes originally planned.

In 1994-95, Silvano Bertolin and his workshop were chosen to work on the Telephus frieze. Restoration of the bas-relief of the Gigantomachy began in 1996 and was not completed until 2004. This frieze, with a total length of 113 meters, with panels each of which weighs approximately 2.5 tons and measures 1 m x 2.30 m, posed a real challenge to restorers.

(4) Detail of the Great Pergamon Altar.

His last years are occupied by the excavation of the remains of Priene, a Greek city of Ionia located at the mouth of the Meander. With various collaborators, he published “Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen zu Pergamon” in 1880-1888 (“Results of the excavations at Pergamon”), and “Reisen in Kleinasien und Nordsyrien” (“Travels in Asia Minor and Syria”) in 1890. Carl Humann died on April 12, 1896 in Smyrna (now İzmir, Turkey) and was buried in the Catholic cemetery in İzmir. His remains were reinterred in Pergamon in 1967, just south of the altar. As if he could not detach himself from his discovery, even after his death.

What is Gigantomachy?

The Gigantomachy was the term used for the war between the gods and the Giants who were the children of Gaia, born from the blood that flowed from the wound of her husband Ouranos (The Sky) when she was mutilated by her son the Titan Cronus. Above all, it recounts the initial conflict of the first elemental gods, and the goal of the Giants was to overthrow the Olympians, the Greek deities who settled on Mount Olympus. In fact, they wanted to overturn the order of things, to destroy the civilized form of the Greek world in the face of the disorderly and chaotic passions of the Giants.

We can interpret this mythological battle as a genealogical conflict, a fundamental order intimately linked to the human conception of the family. That said, it may depict the military victory of the Attalids over the barbarians. A tribute plastered on marble, idealizing the Attalids, imbuing a divine law applicable to man, and above all to the inhabitants of Pergamum.

(5) Carl Humann

(5) Carl Humann

Sources and references:

-Anabasis of Xenophon.

-Strabo.

-Universalis.

-Illustrative image of the Pergamon Altar, deutschland.de.