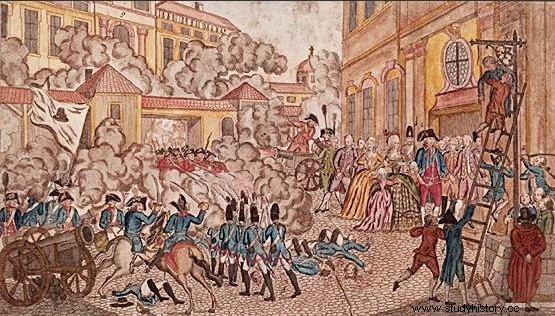

August 10, 1792 is a great insurrectional day of the French Revolution during which Parisians stormed the Tuileries Palace and ended the constitutional monarchy. It originated in a manifesto by the Duke of Brunswick, head of the Prussian army, which promised the revolutionaries terrible reprisals if the royal family was threatened. The Parisians respond with an insurrection which leads to the capture of the Tuileries Palace where Louis XVI resides, after a violent battle which leaves more than 1,000 dead among the defenders. The King, who has taken refuge in the Legislative Assembly with his family, is suspended and locked up in the Temple tower with his family.

August 10, 1792 is a great insurrectional day of the French Revolution during which Parisians stormed the Tuileries Palace and ended the constitutional monarchy. It originated in a manifesto by the Duke of Brunswick, head of the Prussian army, which promised the revolutionaries terrible reprisals if the royal family was threatened. The Parisians respond with an insurrection which leads to the capture of the Tuileries Palace where Louis XVI resides, after a violent battle which leaves more than 1,000 dead among the defenders. The King, who has taken refuge in the Legislative Assembly with his family, is suspended and locked up in the Temple tower with his family.

1792:the King alone against the divided revolutionaries

Isolated in the Tuileries Palace since his flight on June 20, 1791, Louis XVI lost all his support and embarked on a warlike policy which, he thought, would allow him to regain his throne once the Revolution was crushed by foreign armies. The last aristocrats, supporters of absolute monarchy, left France and met partly in Coblentz from where they prepared their return with the help of foreign courts. However, Louis XVI knows very well that this traditional nobility only wants to take power by force by keeping a puppet King or even forcing him to abdicate in favor of the young and easily influenced Dauphin.

The king can hardly count on the Feuillants (which brings together supporters of the constitutional monarchy) who have gradually deprived the monarch of his powers since 1789, and who are very divided on the subject of the war. Supporters of La Fayette are in favor while those of Lameth refuse any conflict that risks fanning the revolutionary fire within. Despite the obstruction of Louis XVI, they still approached it to escape possible reprisals from the Emigrants. Lafayette meanwhile, dreams of a return to the forefront of the political scene from which he is excluded.

Greatly encouraged by the King, the Legislative Assembly declared war on the King of Bohemia and Hungary on April 20, 1792. The Girondins by the voice of Brissot and Roland, wing left of the Legislative Assembly, blindly go to war. Defending a liberal economic policy, they expect substantial benefits from the exploitation of the lands and ports of Northern Europe. Certain of the victory of the revolutionary troops, they see it as a means of forcing the King to accept the Revolution or to drop the mask. They succeeded by intimidation in imposing a Girondin ministry on the King, convinced that the sovereign would not dare to take such a serious decision as to dismiss his ministers if they did not grant him the countersignature necessary for the application of the veto.

May 17, 1792, the Girondin ministry becomes aware of the intrigues of the Feuillants and Lafayette who communicate with the Emperor and explicitly promise to march on Paris and close the Jacobins club. They also know that the general refuses to lead his armies into war. Lafayette and the Feuillants invite the King to the Resistance. The Girondins prefer to hide these maneuvers and negotiate with Lafayette. Under these conditions, the King sees himself as the arbiter of the parties. Despite Brissot's confidence, the King dismissed the Girondin ministry on June 12. The Feuillants applaud; one of them, Adrien Duport, did not hesitate to advise the King to set up a Dictatorship after the dissolution of the Assembly. But the King does not intend to give them power.

May 17, 1792, the Girondin ministry becomes aware of the intrigues of the Feuillants and Lafayette who communicate with the Emperor and explicitly promise to march on Paris and close the Jacobins club. They also know that the general refuses to lead his armies into war. Lafayette and the Feuillants invite the King to the Resistance. The Girondins prefer to hide these maneuvers and negotiate with Lafayette. Under these conditions, the King sees himself as the arbiter of the parties. Despite Brissot's confidence, the King dismissed the Girondin ministry on June 12. The Feuillants applaud; one of them, Adrien Duport, did not hesitate to advise the King to set up a Dictatorship after the dissolution of the Assembly. But the King does not intend to give them power.

The homeland in danger

The Girondins, somewhat irritated by the excessive use that Louis XVI made of his right of veto, embarked on a vehement campaign against the King. Thanks to the mobilization and influence of Mayor Pétion and the head of the National Guard Santerre, they organized a demonstration on June 20 at the Tuileries. Workers and craftsmen from the suburbs went there en masse and violently demanded that the King himself suspend his veto. Insulted, threatened, the King refuses and rejects the maneuver by his placidity.

At the same time, on the 29th, he refused the outstretched hand of Lafayette who offered, under the pretext of a review of the national guard to carry out nothing less than a coup d'etat. Subsequently, he appeared before the Assembly and demanded the dissolution of the Jacobins and measures against the "anarchists", the royalist reaction to the demonstrations of the 20th was so strong that he was acclaimed there. In fact, Louis XVI is playing an imprudent card, he is only waiting for one thing:the arrival of foreign troops in Paris despite the repeated proposals of the Feuillants. It therefore continues its policy of obstruction and its intrigues, communicating with foreign courts.

At the same time, on the 29th, he refused the outstretched hand of Lafayette who offered, under the pretext of a review of the national guard to carry out nothing less than a coup d'etat. Subsequently, he appeared before the Assembly and demanded the dissolution of the Jacobins and measures against the "anarchists", the royalist reaction to the demonstrations of the 20th was so strong that he was acclaimed there. In fact, Louis XVI is playing an imprudent card, he is only waiting for one thing:the arrival of foreign troops in Paris despite the repeated proposals of the Feuillants. It therefore continues its policy of obstruction and its intrigues, communicating with foreign courts.

Having failed his Dix-Huit Brumaire, Lafayette left Paris to join his army. His effigy is burned at the Palais-Royal. Faced with danger, the Jacobins united, Brissot and Robespierre demanded punishment against Lafayette, and, in the Legislative Assembly, the Girondins circumvented a new royal veto by calling on Federated States from all departments to celebrate July 14 in Paris. Already 500 Marseillais are on their way to the capital.

Faced with the advance of numerous troops towards the borders, on July 11 the Assembly then proclaimed "The Fatherland in danger":the administrative bodies and the municipalities sit permanently, new battalions of volunteers are raised and already 15,000 Parisians are enlisting. These exceptional measures aim to put popular and military pressure on the King, of whom no one is fooled by his double game... It was in an icy atmosphere that the royal couple attended the Fête de la Fédération on the 14th in front of thousands of Federated. Indeed, the feuillant ministry, divided, preferred to resign. The arms of emigrant families are burned there. No one shouts "Vive le Roi" anymore, but many spectators had chalked "Vive Pétion" on their hats.

It was then that the Girondins will secretly contact the court hoping to recover the ministry now available. From then on, they will try to stifle "the regicide factions which want to install the Republic". An unacceptable turnaround for the people who feel betrayed as the enemy threatens and issues a very clumsy ultimatum.

It was then that the Girondins will secretly contact the court hoping to recover the ministry now available. From then on, they will try to stifle "the regicide factions which want to install the Republic". An unacceptable turnaround for the people who feel betrayed as the enemy threatens and issues a very clumsy ultimatum.

The Parisian uprising

On July 25, the so-called Brunswick manifesto is published. In reality it is a text written by an emigrant, the Marquis de Limon and advocated by Fersen. This pamphlet promises to reduce Paris to ashes if the King is endangered. It's a thunderclap; indeed, even if the king's intrigues were less and less in doubt, it is an unequivocal admission of treason. This will trigger a strong popular reaction outside of party action.

The Parisian sections rumble and unanimously send minus one (namely 47 sections) Pétion to the Assembly to solemnly demand the forfeiture of the king. The Girondins tried in vain to stifle the wind of revolt which was becoming more and more insistent. The section of the Quinze-Vingt (that of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, one of the most revolutionary) threatens to ring the tocsin on August 10 if the forfeiture of the king is not pronounced. As for the king, he called the Swiss Guards from Rueil and Courbevoie to defend himself.

Fédérés from all departments, made up of ordinary people, come together in committees to coordinate their movement. They were encouraged to stay in Paris after July 14 to pressure the king. Their committee met regularly at the carpenter Duplay's, rue Saint-Honoré, where Robespierre lived, who was very active with them to find them accommodation with the patriots and thus bind them to the people who revolted. The sections and the Federates are getting ready to march together on the Tuileries.

This popular insurrection took place independently of the parties, even if those who were soon to be called the Montagnards supported them and encouraged them to organize themselves:Robespierre, Marat who published a new appeal to the Federated States urging them to action. No future or present political figure has actually participated directly in the insurgency. Danton is often cited as the "man of August 10" but he only returned to Paris from his home in Arcis-sur-Aube on the evening of August 9.

The Assembly is powerless:on August 8 it had absolved Lafayette, on the 9th it does not dare to address the petition of the 47 sections on the forfeiture of the king and separates without debate at 19 'o clock. In the sections the insurrectionary slogans are distributed and at 11 p.m. the tocsin rings...

August 10, 1792:capture of the Tuileries

During the night, Santerre raised the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and Alexandre the Faubourg Saint-Marceau and the Federated Marseilles were boiling. The sections sent revolutionary commissioners to the Hôtel de Ville who deposed the legal municipality and founded the insurrectional Commune, they ensured the passivity of Pétion and executed the Marquis de Mandat, commander of the national guard which had recently been made up of inactive citizens (who do not pay enough tax to vote).

During the night, Santerre raised the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and Alexandre the Faubourg Saint-Marceau and the Federated Marseilles were boiling. The sections sent revolutionary commissioners to the Hôtel de Ville who deposed the legal municipality and founded the insurrectional Commune, they ensured the passivity of Pétion and executed the Marquis de Mandat, commander of the national guard which had recently been made up of inactive citizens (who do not pay enough tax to vote).

The Sans-culottes of all sections go to the Tuileries Palace, they raise the red flag for the first time, it is inscribed:"Martial law of the Sovereign People against the rebellion of the executive power”. It is a revenge of July 17, 1791, during this day Lafayette and Bailly had fired on the unarmed people who demanded the Republic. During this shooting which left 50 dead, the national guard had raised the red flag of martial law.

Immediately, the national guard and the gunners sided with the insurgents, only the Swiss guards and a few aristocrats remained to defend the king. Despite attempts at fraternization with the Swiss, the zealous royalists forced the fire. The insurgents are furious at this ultimate betrayal and with the help of the Brest and Marseille Federated States they break the resistance of the defenders of the palace which ends up falling. The insurgents count 1000 killed and wounded.

The fall of the monarchy

When the demonstrators arrived, the royal family fled the Tuileries Palace and went to the Assembly to take refuge there. Embarrassed and powerless, the latter declared that they wanted to protect the “constituted authorities” before ordering the suspension of the King of France under pressure from the victorious insurgents. They voted to convene a National Convention so demanded by Robespierre and decried by Brissot. The guard of the king was entrusted to the insurrectional Commune which locked him up in the Temple.

Thus fell the throne after a thousand years of unbroken monarchy. But with the throne fell its last defenders, the minority nobility who had promised themselves to lead and tame this Revolution. But the Girondin party itself, which wanted to prevent this insurrection by negotiating at the last moment with the Court, was weakened. The passive citizens, the proletarians and their spokesperson:the Montagnards took their revenge on July 17, they are the big winners of this day. August 10, 1792 is a Revolution in itself:it is the advent of the Republic. Tried for treason, Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette were guillotined the following year.

Bibliography

-Mathiez, Albert, August 10, 1792, Editions de la Passion, 1989.

- The capture of the Tuileries and the sacrifice of the Swiss Guard:Ten August 1792, by Alain-Jacques Czouz-Tornare. Editions SPM, 2017.

- Mathiez, Albert, The French Revolution volume 1:the fall of royalty, Armand Colin, 1933.