Following the Norman invasions and urban insecurity, the first medieval cities were of little importance in France, exceeding rarely the 5,000 inhabitants. But with the progressive establishment of peace, from the 11th century onwards, towns and cities multiplied around cathedrals and trade fairs. Taking advantage of their growth, the cities experienced a communal movement, a moment of claims by the bourgeoisie against the lord of the city. By violence or against payment, this movement obtains a charter, which fixes the rights and the freedoms of each one. The city of the Middle Ages then becomes a small state and begins an almost continuous growth until the Hundred Years War.

Following the Norman invasions and urban insecurity, the first medieval cities were of little importance in France, exceeding rarely the 5,000 inhabitants. But with the progressive establishment of peace, from the 11th century onwards, towns and cities multiplied around cathedrals and trade fairs. Taking advantage of their growth, the cities experienced a communal movement, a moment of claims by the bourgeoisie against the lord of the city. By violence or against payment, this movement obtains a charter, which fixes the rights and the freedoms of each one. The city of the Middle Ages then becomes a small state and begins an almost continuous growth until the Hundred Years War.

Ancient medieval cities in France

Before the year 1000, following the Norman invasions of the previous centuries, the cities and the popular masses were reduced. The communities withdrew into themselves, preferring to offer the invader a confined space and a close-knit city population to defend themselves. The cities of Antiquity have therefore not disappeared, but their density of occupation has weakened and, above all, their role in political and economic life has diminished.

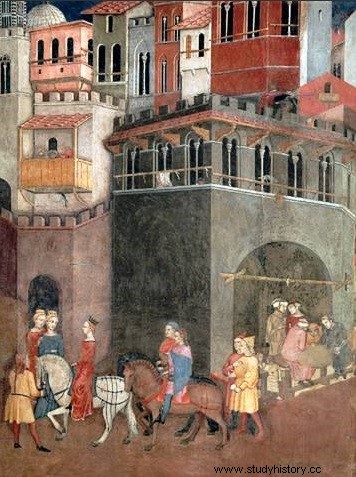

In the 10th century AD. J.-C., the invasions of the Normans come to an end. The French populations gathered around the small ancient cities. The towns and cities offer different faces, but all are located at the crossroads of more or less important traffic routes. The oldest cities, small entities most often surrounded by the ancient Roman walls, were formed around a castle leaning against the wall or a simple tower on its feudal mound, or even around a fortified abbey. The most recent cities, whose development is permitted thanks to newly acquired peace and security, take root at the crossroads of roads and waterways. Often, these new entities are so many stops on the way to a pilgrimage or a commercial market.

In the 10th century AD. J.-C., the invasions of the Normans come to an end. The French populations gathered around the small ancient cities. The towns and cities offer different faces, but all are located at the crossroads of more or less important traffic routes. The oldest cities, small entities most often surrounded by the ancient Roman walls, were formed around a castle leaning against the wall or a simple tower on its feudal mound, or even around a fortified abbey. The most recent cities, whose development is permitted thanks to newly acquired peace and security, take root at the crossroads of roads and waterways. Often, these new entities are so many stops on the way to a pilgrimage or a commercial market.

Urban habitat is dense and cramped. As the population grew, neighborhoods developed outside the ramparts. When the suburbs ask for protection, new concentric enclosures are gradually erected. Everywhere, the axes of circulation, often narrow, interpenetrate, to the point of creating tortuous networks which preserve from the wind but which the fires devastate. The floors of the wooden houses, built in corbelling*, protect passers-by from bad weather and the sun.

Other constructions, of a public nature, are gradually appearing:on the one hand, bridges and quays to help river traffic and the crossing of waterways. 'water; on the other hand, paved arteries. The rudimentary wastewater management system is often reduced to channeling certain waterways, leaving most of the open drainage on the street floor itself.

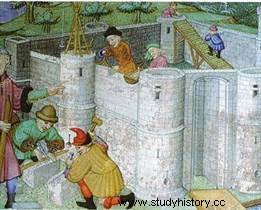

Building materials in the Middle Ages

The masonry of houses is often made of cob, with the use of a wooden frame to reinforce the structure. Brick, highlighted in Merovingian and Carolingian public architecture, began to impose itself as a construction material from the 12th century, given its architectural and decorative qualities. The taste for simple facings in brick appears in certain Cistercian abbeys, but also in certain cathedrals, castles and urban agglomerations, in particular in the county of Savoy.

The architectural achievements of the monasteries constituted, until the 12th century, one of the essential driving forces for the construction in stone and quarrying. The complexity of the various monumental constructions of the Gothic age, compared to the Romanesque age of the monasteries, implies standardizing the size of the Liers, and defining precise calibres.

The architectural achievements of the monasteries constituted, until the 12th century, one of the essential driving forces for the construction in stone and quarrying. The complexity of the various monumental constructions of the Gothic age, compared to the Romanesque age of the monasteries, implies standardizing the size of the Liers, and defining precise calibres.

The construction of cathedrals, which intensified with the development of Gothic art, required the importation of cut stone when it was lacking, developing the waterways and land routes from, in particular, the quarries of Anjou and Touraine. In addition, municipal constructions of city walls and belfries* also require the use or reuse of many stones.

Trade places

The development of cities and all agglomerations, located at the crossroads of significant communication routes, promote trade, particularly during local and regional markets, then during larger trade fairs. All productions are sold there, both food from the countryside and monasteries and foodstuffs and objects, made by craftsmen or brought from more distant lands (cloth, linen, goldsmithery, spices... ).

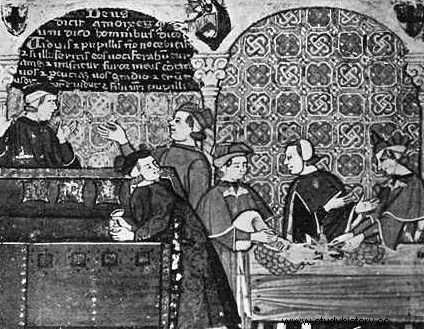

Merchants settle down for a long time and associate in large organizations called guilds or hanses. Rejecting the old seigniorial regime that was too restrictive, the merchants sought to acquire franchises, guaranteeing the privileges of the new class they formed:the bourgeoisie. These new bourgeois now benefited from precise rights and duties, duly enacted in communal charters drawn up by the local lords and the former ecclesiastical authorities in the name of the inhabitants of the new commune, grouped together in mutual aid associations:the "sworn communes .

The Charters are most often kept in buildings symbolizing the new power of the communes:the belfries. From now on, these legal documents ensure the explicit security of goods and transactions, the guaranteed exercise of fair justice, as well as the increasingly autonomous management of the economy by the municipalities. To obtain these Charters, negotiations are carried out, mixing popular revolts with financial compensation.

Other new cities, created by the lords themselves, often benefit from variable tax exemptions, but are still fairly subject to feudal authority, under the aegis of an often very tolerant charter. These are the "new towns" or "free towns".

The administration of municipalities

In the communes, the rights recently granted to the bourgeoisie give rise to the payment of specific taxes, the implementation place of special courts composed of bourgeois, as well as the institution of communal management of public property and buildings (communal police on the markets, maintenance of the city walls, management of the markets, etc.). All common expenses are borne by the city authorities, mainly through taxes levied on the purchase and sale of commodities.

In the communes, the rights recently granted to the bourgeoisie give rise to the payment of specific taxes, the implementation place of special courts composed of bourgeois, as well as the institution of communal management of public property and buildings (communal police on the markets, maintenance of the city walls, management of the markets, etc.). All common expenses are borne by the city authorities, mainly through taxes levied on the purchase and sale of commodities.

The municipality, that is to say an assembly composed of elected councillors, is subject to the authority of the mayor They can seal deeds, buy land or mint coins . To facilitate commercial procedures, merchants set up counters in residences whose stone construction, formerly reserved for seigniorial buildings and ecclesiastical buildings, reflects economic success. Establishments that exchange currencies or grant loans are gradually appearing.

Notables and corporations

Controlling the finances of the municipalities, the bourgeois gradually played a decisive political role in the management of the city. The richest and most powerful among them, in this case the members of the most influential urban families or the descendants of the nobility freshly involved in economic affairs, monopolized the main public functions. The symbol of their power is particularly embodied by town halls, particularly in the North of France.

Controlling the finances of the municipalities, the bourgeois gradually played a decisive political role in the management of the city. The richest and most powerful among them, in this case the members of the most influential urban families or the descendants of the nobility freshly involved in economic affairs, monopolized the main public functions. The symbol of their power is particularly embodied by town halls, particularly in the North of France.

Faced with the monopoly exercised by the bourgeoisie in the management of cities, the workforce and craftsmen of the communes are beginning to fight back. They gradually came together in associations, formed according to the various professions exercised. Each of these corporations of tradespeople is strictly regulated and hierarchical, and takes into account the role played by the three categories of its members:the masters (at the head of a workshop), the companions (salaried workers), and the apprentices (in training).

Demanding their share of the exercise of power, the corporations opposed themselves more and more violently to the notables of the cities and ended up fomenting strikes and local or even regional seditions, including repression sometimes forces sovereigns to intervene to arbitrate conflicts. When they manage to obtain communal responsibilities, they only delegate the exercise of power to their most important representatives in the hierarchy, in this case the masters.

The city in the Middle Ages, place of worship

At the heart of the episcopal city, center of a bishopric, the cathedral is the symbol of local spiritual power. The circumscriptions of Christian France are the dioceses, at the head of which is placed the bishop, normally elected by the clergy and representatives of the population of the diocese, but most often chosen by the sovereigns and the pope.

Larger circumscriptions, led by archbishops from the main cities of the former Roman provinces (Lyon, Reims, Bordeaux , ...), coordinate the efforts of the different bishoprics. Having a power essentially of a religious order, the bishop can also resort to excommunication or interdict to weigh with all his weight in temporal affairs.

Larger circumscriptions, led by archbishops from the main cities of the former Roman provinces (Lyon, Reims, Bordeaux , ...), coordinate the efforts of the different bishoprics. Having a power essentially of a religious order, the bishop can also resort to excommunication or interdict to weigh with all his weight in temporal affairs.

Dominating all the neighboring houses, the cathedral places, by the scale of its structure, the power of the bishops in the center of the cities. But with peace restored, and faced with the growing number of faithful in the cities, the episcopal churches, where the bishop sits on his cathedra, constantly need to be enlarged. Gigantic projects are carried out in the main cities. The towers and vaults are, with each new construction undertaken, pushed higher and higher, sometimes resulting in incidents and collapses.

Gothic art, relieving the walls with the help of buttresses and buttresses, allows stained glass windows to be inserted into the heart of the building. They illuminate the nave with their colorful bursts and illustrate different episodes narrated in the biblical text. The wood and stone sculptures, with abundant and mysterious motifs, offer a well-documented vision of the world and the beyond.

The successes of intellectual life

After the short intellectual renaissance of the Carolingian era, cultural life, at the dawn of the year one thousand, slowed down somewhat. It was not until the first decades of the 11th century that cultural life resumed with renewed vigor in monastic establishments. The schools of the estates, attached to the parishes, to the abbeys or to the cathedral church, dispense lessons centered on theology. They also teach the basics of science such as geometry, arithmetic, astronomy and music.

Oral teaching respects the rules of dialectics enacted at the beginning of the 12th century by Pierre Abélard, taking into account, when solving a problem or simply dealing with a question, evidence for and against.

Oral teaching respects the rules of dialectics enacted at the beginning of the 12th century by Pierre Abélard, taking into account, when solving a problem or simply dealing with a question, evidence for and against.

Because of the success and multiplication of monastic and episcopal schools, the Church places chancellors at the head of these establishments. These canons, specialized in education and whose license to teach is directly granted by the bishop, are directly placed under the close control of the diocese. Some schools, with an eminently respectable fame and reputation (Paris, Toulouse, etc.), gradually became precursors of the universities which, at the beginning of the 13th century, were born in various European cities (Bologna. ..). In 1200, Philippe Auguste granted privileges to masters and schoolchildren in Paris, which Pope Gregory IX confirmed in 1231 with the bull Parens scientiarum. The University of Paris is thus created.

Bibliography

- The city in the Middle Ages, by Jacques Heers. Plural, 2010.

- Cities in the Middle Ages in French Space XIIth - XVIth Century, by David Rivaud. Ellipses, 2012.

- The World of Cities in the Middle Ages, 11th-15th Century, by Simone Roux. Hachette, 2004.