Dynasty of Frankish kings descended from Merovée, the Merovingians reigned over Gaul until 751. This matrix dynasty of French royalty was for a long time the victim of a "black legend", maintained from the 6th century by Grégoire de Tours, then by their successors, the Carolingians, under the pen of Einhard. The Merovingians thus became the "lazy kings" of images for schoolchildren until the 19th century (and beyond...). Apart from Clovis, and for other reasons Dagobert I , the Merovingian period was like a black hole in the history of France. However, these kings and queens were on the border between the end of a “barbaric” Antiquity and a Middle Ages where France was going to be built.

Dynasty of Frankish kings descended from Merovée, the Merovingians reigned over Gaul until 751. This matrix dynasty of French royalty was for a long time the victim of a "black legend", maintained from the 6th century by Grégoire de Tours, then by their successors, the Carolingians, under the pen of Einhard. The Merovingians thus became the "lazy kings" of images for schoolchildren until the 19th century (and beyond...). Apart from Clovis, and for other reasons Dagobert I , the Merovingian period was like a black hole in the history of France. However, these kings and queens were on the border between the end of a “barbaric” Antiquity and a Middle Ages where France was going to be built.

The mythical origin of the Merovingians

The Merovingian dynasty is rooted in a tribe of Salian Franks, descended from a branch of the Frankish people settled between the Rhine and the Scheldt. It owes its name to the legendary Merovée, son or nephew of Clodion le Chevelu, who would have reigned from 448 to 457 over a tribe of Francs Saliens, and would have been the ally of the Roman general Aetius against the Huns during the battle of the Catalaunian fields. . Its power is reduced, at the origin, to the only kingdoms of Cambrai and Tournai, between France and current Belgium. After four more or less legendary sovereigns who were only tribal chiefs, Clovis I, king from 481 to 511 and son of Childeric I, became its true founder through his many conquests.

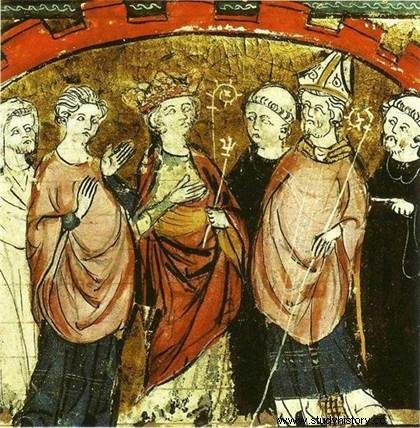

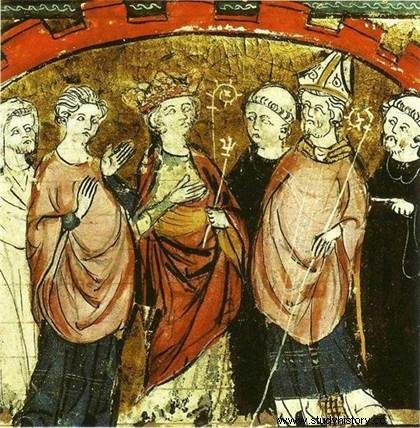

In 498 (?), Clovis and his warriors were baptized by the bishop of Reims Rémy, thus obtaining the support of the Catholic clergy and the Pope of Rome. He reduced the Burgundians to tribute (500) and, at the battle of Vouillé (507), crushed the Visigoths, who were rejected in Spain. Master of almost all of Gaul, he realized shortly after under his authority the union of the Francs Saliens and Ripuaires. Supreme leader of the Germanic tribes settled in Gaul, Clovis worked to merge Frankish customs and Gallo-Roman legislation, giving rise to the Salic law of the Frankish kings.

In 498 (?), Clovis and his warriors were baptized by the bishop of Reims Rémy, thus obtaining the support of the Catholic clergy and the Pope of Rome. He reduced the Burgundians to tribute (500) and, at the battle of Vouillé (507), crushed the Visigoths, who were rejected in Spain. Master of almost all of Gaul, he realized shortly after under his authority the union of the Francs Saliens and Ripuaires. Supreme leader of the Germanic tribes settled in Gaul, Clovis worked to merge Frankish customs and Gallo-Roman legislation, giving rise to the Salic law of the Frankish kings.

The "one and divisible" Frankish kingdom

At his death in 511, Clovis bequeathed to his sons an immense kingdom, with Paris as its capital and Catholicism as its religion. Then begins what may seem like a paradox, especially if we compare it to what the dynasties that succeed the Merovingians will do:divided between the sons of Clovis, the Frankish kingdom remains nonetheless united. Claude Gauvard thus speaks of a kingdom “both one and divisible”. It is this apparent paradox that allows the Merovingians to continue to expand their territory, to become a continental power, and to resist civil wars. One time only…

The division of 511 between Thierry, Clodomir, Clotaire and Childebert is inspired by the Roman system of civitates , thus confirming the continuity between the Frankish kingdom and the imperial tradition. If the latter is divided territorially and has four capitals (Reims, Paris, Orléans and Soissons), political unity is very real, and largely because it is based on blood ties.

However, the situation should not be idealized, and succession disputes quickly appeared, with the death of the first sons of Clovis. First Clodomir (524), one of whose sons, Cloud, must flee and become a cleric before dying and giving his name to a well-known town. The rest of Clodomir's kingdom is shared between the three surviving brothers. When the eldest, Thierry, dies, things get a little more complicated because his son, Théodebert, enjoys his prestige, which is superior to that of his uncles. He took the opportunity to affirm ambitions that went beyond the borders of Gaul since he minted gold coins in his effigy, provoking the anger of the Emperor Justinian. Théodebert died in 548, without having achieved his goals, despite conquests in Alemania and Bavaria.

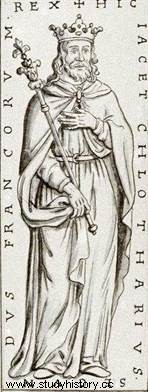

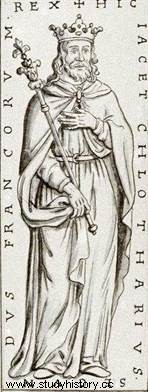

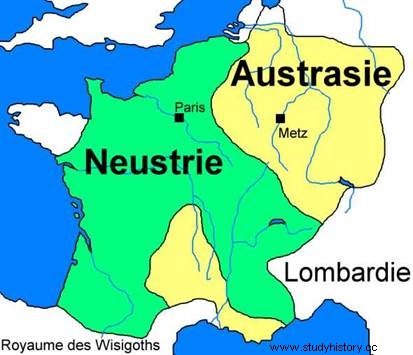

The situation finally settles with the extinction of the elder branch and the disappearance of Childebert. This allows Clotaire I to reign alone until 561. A new division occurs at his death, once again between his sons, who are only three in 567 (death of Charibert I). It was then that the Frankish kingdom was divided into three regions that will know posterity:Austrasia (Rhine region, Champagne and Aquitaine), Burgundy (former Burgundian kingdom and kingdom of Orléans), and Neustria (region of Tournai , “Normandy” and Paris region). This decisive moment quickly coincided with a real civil war, which broke out in 570. Previously, the Frankish kingdom was able to assert itself internationally.

The Merovigians, an “international” power?

The sons of Clovis do not intend to stop with their father's victories and, despite their divisions within the kingdom, are united as regnum francorum for foreign policy. Clovis had distinguished himself mainly with the conquest of Aquitaine, allied with the Burgundians. Yet they are the first victims of his successors. The Merovingians take advantage of the internal difficulties in the Burgundian kingdom, mainly religious quarrels between Catholics and Arians, to attack for the first time in 523, but they are repelled. The same is true a year later, and the Franks lose Clodomir! More cautious, they wait ten years to try the adventure again, led by Childebert I, Clotaire I and Théodebert I. They emerge victorious, and the Burgundian kingdom is swallowed up by the Frankish kingdom, while being shared between the victors.

The Merovingian victories attract the attention of the emperor in Constantinople. The main issue is the domination of Italy, over which the Ostrogoths still reign. The latter, who understood that the Franks were a danger and potential allies of the Byzantines, offered them Provence to obtain their neutrality against the emperor. The Franks did not need to be asked and entered Provence in 537, thus gaining access to the Mediterranean! With this acquisition, the Franks almost reconstituted the unity of Roman Gaul; only Septimania remained, which they were unable to wrest from the Visigoths.

The Merovingian victories attract the attention of the emperor in Constantinople. The main issue is the domination of Italy, over which the Ostrogoths still reign. The latter, who understood that the Franks were a danger and potential allies of the Byzantines, offered them Provence to obtain their neutrality against the emperor. The Franks did not need to be asked and entered Provence in 537, thus gaining access to the Mediterranean! With this acquisition, the Franks almost reconstituted the unity of Roman Gaul; only Septimania remained, which they were unable to wrest from the Visigoths.

Further north, Thierry I and Clotaire I ally with the Saxons and defeat the King of Thuringia, annexing the western part of his kingdom in the same year as the conquest of Provence . Two years later, Theodebert I conquered Alemania and Bavaria, and for a time northern Italy. It was in fact necessary to wait for the arrival of the Lombards in the 560s for the Frankish advance to be stopped. The civil war is also no stranger to it.

Civil war strikes the kingdom of the Merovingians

The death of Charibert I, son of Clotaire I, in 567 brought about a new division. But this time, it provokes a real civil war between the three brothers of the king:Sigebert, Chilpéric and Gontran. War also due to a risky strategy of matrimonial alliances between the Merovingians and their neighbors – and rivals – Visigoths.

Women played a central role in political struggles at the end of the sixth century. The rivalry is exacerbated between Brunehaut, wife of the King of Austrasia Sigebert I, and Frédégonde, wife of Chilpéric I, King of Neustria. The first is a Visigothic princess, daughter of King Athanagild, and she accuses the second of having had her sister, Galswinthe, the previous wife of Chilperic I, killed! The situation is aggravated by the fact that the king of the Visigoths dies without an heir, which stirs up covetousness, in particular that of Chilpéric precisely...

This triggers the faide , characteristic of the Germanic peoples, and the infernal spiral. The intrigues of the two queens lead to the assassinations of Sigebert I (575), then of Chilpéric I (584)! Gontran tries to keep himself a little away from the conflict, which becomes armed from the beginning of the 570s. On the death of her husband, Brunehaut holds the reality of power in Austrasia, and puts forward his son Childebert II. This quickly opposes the son of Frédégonde, Clotaire II, and the war resumes even more vigorously, despite the attempts at peace initiated by Gontran (Pact of Andelot, 587).

This triggers the faide , characteristic of the Germanic peoples, and the infernal spiral. The intrigues of the two queens lead to the assassinations of Sigebert I (575), then of Chilpéric I (584)! Gontran tries to keep himself a little away from the conflict, which becomes armed from the beginning of the 570s. On the death of her husband, Brunehaut holds the reality of power in Austrasia, and puts forward his son Childebert II. This quickly opposes the son of Frédégonde, Clotaire II, and the war resumes even more vigorously, despite the attempts at peace initiated by Gontran (Pact of Andelot, 587).

The situation became a little more complicated with the death of Gontran in 592, and the entry into the running of the sons of his nephew, Childebert II, who had succeeded him, but was died four years later. Théodebert II and Thierry II thus continue the war against Clotaire II, quickly in difficulty.

However, Queen Brunehaut was increasingly contested in Austrasia, and she had to take refuge in Burgundy with Thierry II. But there too she attracted the wrath of the local aristocracy. In addition, the sons of Childebert II enter into rivalry in turn, to the delight of Clotaire II, who did not ask for so much. Thierry II locks up his brother Theodebert II in a monastery, then dies in 613. Brunehaut then tries to regain control and place one of his great-grandsons, but she is delivered by the aristocrats to his rival, who has her executed after a long ordeal.

The end of Antiquity, the beginning of the Middle Ages?

Some current historians, including Geneviève Bührer-Thierry and Charles Mériaux, mark the end of Antiquity with the death of Brunehaut, a Visigothic princess "still very Roman". The advent of Clotaire II, and especially of his son Dagobert, “[seals] the unity of the Frankish kingdom” (according to the chronicle of Frédégaire), and probably marks its peak, before the emergence of the Pippinides…

The end of the faide having opposed the queens Brunehaut and Frédégonde, then their sons, allowed Clotaire II to ascend the throne alone. The king, and even more his son Dagobert , contribute at the beginning of the 7th century to the height of the Merovingian dynasty. However, the troubles began very quickly, from the successors of Dagobert, and caused the rise in power of what was not yet strictly speaking a dynasty, the Pippinids. The latter, thanks to their strategic role in Merovingian power, ended up supplanting him with a certain Charles Martel.

Clotaire II and the regna

Supposed to be king since 584, Clotaire II ended up ruling alone on the death of his Merovingian rivals and the queen Brunehaut at the beginning of the 610s. However, the Frankish kingdom was still divided into three reigns, Austrasia, Neustria and Burgondie, and the aristocrats were in turmoil. It is then necessary for Clotaire II to legitimize his power and "seal the peace".

Supposed to be king since 584, Clotaire II ended up ruling alone on the death of his Merovingian rivals and the queen Brunehaut at the beginning of the 610s. However, the Frankish kingdom was still divided into three reigns, Austrasia, Neustria and Burgondie, and the aristocrats were in turmoil. It is then necessary for Clotaire II to legitimize his power and "seal the peace".

In 614, inspired by Clovis, he therefore called assemblies in Paris with the aristocrats, but also the bishops, and settled almost simultaneously the religious and political problems of the kingdom, with the Edict of Paris, promulgated in October of that year. Clotaire II thus secured the support of both nobles and clergy, while consolidating his own power. If he personally reigns over Neustria, he remains the preeminent sovereign of the regnum francorum , and does not hesitate to punish the great ones of the other regna with desires for independence, like Godin, who tried to force him to appoint him mayor of the palace of Burgondie in 627.

The tensions still remain, and the king is constantly forced to negotiate with the regna , especially Austrasia. The aristocrats of the latter obtain from the king that he send his young son Dagobert to their home, which allows them to take advantage of the latter's youth to exercise real power over this regnum , which happens to be strategic in the fight against the Avars and Wendes. Among these greats, a certain Pepin I, called de Landen.

The reign of Dagobert I

Two years before his death, Clotaire II once again called the assemblies together and in the promulgated acts the idea of a sacred royalty already began to appear. He died in 629, and his son Dagobert succeeded him, thus leaving Austrasia for Neustria. The legitimacy of Dagobert is apparently not disputed by the great, whether those of Austrasia, where he comes from, or the two other regna . He did however have a brother, Caribert, but he sent him to Aquitaine, where he died in 632. Dagobert began his reign with a trip to Burgundy, to reassure the aristocracy about his intentions. Then he moved to Paris. Saint Eloi, goldsmith of his father Clotaire II and bishop of Saint Ouen, became his main adviser.

The Austrasian "problem" remains. The regnum is powerful, its great therefore difficult to control, occupying strategic positions, as mayor of the palace. Dagobert manages all the same to install his son Sigebert on the Austrasian throne in 632. Two later, he intends for his newborn son, Clovis, the kingdoms of Burgundy and Neustria, thus ensuring his succession. On his death in 639, the Frankish kingdom was again divided.

Dagobert's reign is contemporary with the emergence of Islam, and more particularly with the first Muslim conquests. Like his predecessors, the Frankish king was approached by the Byzantine emperor. But past experiences have served as a lesson and, if there are exchanges of embassies (as in 629), the time is no longer for the alliance. However, we know from Fredegaire that the Franks were probably aware of the troubles of the basileus Heraclius with the Arabs between 637 and 641.

The foreign policy of the Merovingians in the first decades of the seventh century is far removed from Byzantine concerns in the Near East. It is for Dagobert to consolidate the borders of the regnum francorum , mainly in Aquitaine (with Gascony) and Brittany. He got down to it around 635, but if he submitted the Basques, he had to settle for a diplomatic agreement in Brittany, without getting his hands on the region.

In the East, Thuringia, Alemania, then Bavaria were subject to tribute and their rulers appointed by the Franks. Dagobert benefits here from the threat of the Wendes, the Slavs settled in Pannonia; he also fails to submit them. Finally, the Frankish king began to take an interest in Friesland without however being able to really establish a foothold there.

In the East, Thuringia, Alemania, then Bavaria were subject to tribute and their rulers appointed by the Franks. Dagobert benefits here from the threat of the Wendes, the Slavs settled in Pannonia; he also fails to submit them. Finally, the Frankish king began to take an interest in Friesland without however being able to really establish a foothold there.

The “lazy kings” and the mayors of the palace

When Dagobert died in 639, his sons Sigebert III and Clovis II shared the Merovingian kingdom. The first becomes as planned king of Austrasia, the second king of Neustria, as well as the support of Burgundy, which is increasingly autonomous. The problems start quickly.

First in Neustria, where Clovis II is far too young to rule. The exercise of power is shared between his mother Nanthilde, who was not queen but a servant married in 629 by Dagobert because Gomatrude had not given her a male, and the mayors of the palace, Aega first, then Erchinoald . The latter managed to marry the young king to Bathilde, an Anglo-Saxon slave, in 648. The latter took advantage of the death of her husband in 657, then that of the mayor of the palace a year later, to exercise power and attempt to reunite the regnum francorum . Indeed, rivalries are growing with Austrasia.

In the regnum from the East, the influence of the mayors of the palace began during the reign of Dagobert, with Pepin I. The new king, Sigebert III, tries to remove the Pippinids by favoring another family. This did not prevent Grimoald, son of Pépin, from also accessing this strategic post, described by Bishop Didier of Cahors as "rector of the whole court or rather of the whole kingdom". The role of the Pippinids at this time is already so important that historians believed for a time that the death of Sigebert III in 656 could have provoked a first Pippinid "coup d'etat".

It is ultimately only a problem of complex succession, and of rivalry between the mayor of the palace and the queen, but it shows the decisive influence of men in this position, and especially of the Pippinids. It finally takes the intervention of the Neustrians and Bathilde to remove Grimoald and his protege Childebert, whom he had made king at the expense of Dagobert II, son of Sigebert, exiled in Ireland! Yet it was Childeric II, son of Bathilde, who was king of Austrasia in 662.

Rivalries between Merovingians that benefit the Pippinids

The difficulties of the Pippinids are only temporary. The rivalry between Neustria and Austrasia, but also the tensions between greats within the regna , eventually allow their return to the fore.

The difficulties of the Pippinids are only temporary. The rivalry between Neustria and Austrasia, but also the tensions between greats within the regna , eventually allow their return to the fore.

In Neustria, the new mayor of the palace, Ebroïn, dismisses Queen Bathilde in 665 and holds King Clotaire III in his hand. Tensions then explode with the great, amplified in 673 when Ebroïn imposes the son of Clovis II and Bathilde, Thierry III, as successor to Clotaire III, to the detriment of the king of Austrasia Childéric II, favorite of the aristocrats. The situation only got more complicated in the following years, and Neustria fell into civil war. Ebroïn was one of the victims, assassinated in 682. However, if the successive kings were weak and disputed, the very principle of the Merovingian dynasty was not called into question for the moment.

The problems of Neustria eventually reach Austrasia, where Dagobert II is assassinated a few years after his return from exile. The instability and vacancy in the post of mayor of the palace after the death of Wulfoad, rival of Ebroïn, bring the return of the Pippinids, a family still powerful but watched over by the other aristocrats. It was one of them, Duke Pepin II of Herstal, who became mayor of the palace of Austrasia in the early 680s. seizing at the same time the treasure of Thierry III!

The end of the Merovingians

The coming to power of the mayor of the Pépin palace in Herstal marks the beginning of the end of the Merovingians. Yet the mayor of the palace leaves the king in place, content to strip him of the very essence of his power. The latter is in the hands of those who then take the title of "princes", the mayors of the palace of Neustria and Austrasia, from only the Pippinid family. This asserts itself even more with the successors of Pepin II, despite attempts at rebellion by the other greats on the death of the latter in 714. It is his son Charles who imposes himself, against the Neustrians of Rainfroi in the 720s, but also against external enemies, Arab-Berbers in Poitiers in 732, or Frisians two years later.

However, Charles Martel did not make himself king, even on the death of the last Merovingian, Thierry IV, in 737, when he dismissed the successor Childeric III. The last descendants of Clovis, from the accession of Pepin II, have been designated by Carolingian historiography (heiress of the Pippinids) as "the lazy kings". They are placed on the throne by the mayors of the palace, are tossed about according to the winds and rivalries (like Chilpéric II during the Rainfroi/Charles struggle), and no longer exercise any real power.

However, it was not until 751, and the accession of Charles's son, Pepin the Short, that the Merovingian kings gave way to a new dynasty, that of the Carolingians. .

Bibliography

- The Merovingians - Society, power, politics 451-751, by Nicolas Lemas. Armand Colin, 2016.

- The Merovingians, by Jean Heuclin. Ellipses, 2014.

- R. Le Jan, Les Mérovingiens, PUF, 2006.