The Celts are Indo-European peoples originating from the Danube valley, who settled in much of Europe from antiquity. These tribes speak the same language, with variations, and have certain religious beliefs in common. They are the spreaders of the iron civilization in Western Europe. Most historians refuse to speak of a Celtic civilization, instead evoking a Celtic world with linguistic and cultural similarities. Organized into countless tribes and federations with shifting contours, the Celts of Gaul were industrious and ingenious farmers, but also fierce warriors and shrewd traders, in contact with the ancient Mediterranean world.

The Celts are Indo-European peoples originating from the Danube valley, who settled in much of Europe from antiquity. These tribes speak the same language, with variations, and have certain religious beliefs in common. They are the spreaders of the iron civilization in Western Europe. Most historians refuse to speak of a Celtic civilization, instead evoking a Celtic world with linguistic and cultural similarities. Organized into countless tribes and federations with shifting contours, the Celts of Gaul were industrious and ingenious farmers, but also fierce warriors and shrewd traders, in contact with the ancient Mediterranean world.

What are the origins of the Celts?

The Celts were an “Indo-European” people who originated in Central Asia and settled in southern Russia around 2500 BCE. During the early Bronze Age, their military aristocracy went on numerous plundering expeditions to the Near East and Greece, then the group dispersed around 2000 BC. Some of the Celts headed for the North Sea, another for Central Europe (Bohemia), where they developed the bronze industry.

Around 1250, the Celts in Europe gave birth to the so-called "urnfield" civilization, due to the large number of funeral urns containing the ashes of the deceased. These burials also reveal great art in the manufacture of ceramics and long, straight swords. Fields of this type appeared in France from about 1200.

Around 1250, the Celts in Europe gave birth to the so-called "urnfield" civilization, due to the large number of funeral urns containing the ashes of the deceased. These burials also reveal great art in the manufacture of ceramics and long, straight swords. Fields of this type appeared in France from about 1200.

Celtic expansion:Halstat and La Tène periods

Around 1000 BC. BC developed in the Austrian Alps the Celtic civilization known as Hallstatt, named after the town near Salzburg where about 20,000 objects were found scattered in numerous tombs. These reveal the wealth of the Celtic people, who produced refined jewelry, decorated vases, and, mastering the work of iron, formidable weapons. This warlike people continued its expansion towards the west, southern Germany, Switzerland, and at the beginning of the 8th century in present-day France.

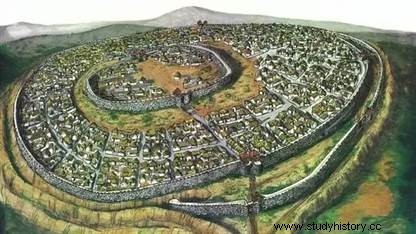

Around 500 BC. BC, beginning of the Iron Age in northern Europe, the Celts occupied all of northern and western Gaul, from Carcassonne to Switzerland, and had founded the so-called La Tène civilization (village located near of Neuchâtel, where vast tombs containing two-wheeled chariots were found in 1881). This people built wooden and earthen houses grouped on fortified oppidums, built places of worship and used chariots, iron swords and helmets to fight.

The Celts of La Tène undertook the conquest of new territories further south in the 5th century:they submitted part of Provence, while in -390 Ambicat, king of the Celts Bituriges, seized northern Italy (which will be called "Cisalpine Gaul"). The Senons of Brennus pushed the audacity to rub shoulders with the Romans and plundered the city of Rome (-390). Only the Capitol was spared thanks to the sacred geese whose cries alerted the defenders.

The Celts of La Tène undertook the conquest of new territories further south in the 5th century:they submitted part of Provence, while in -390 Ambicat, king of the Celts Bituriges, seized northern Italy (which will be called "Cisalpine Gaul"). The Senons of Brennus pushed the audacity to rub shoulders with the Romans and plundered the city of Rome (-390). Only the Capitol was spared thanks to the sacred geese whose cries alerted the defenders.

Other Celts pushed further east:in the early 2nd century, they settled in the Balkans and sacked Greece. They then founded a kingdom in Thrace and around the Black Sea, then in Asia Minor (Galatia, country of the Galatians). Indeed, this term now used by the Greeks to designate the Celts would mean “those from elsewhere” or “the invaders”. Cato the Elder will translate it by “Galli”, which will give “Gauls”. Most of the Gauls are therefore, ultimately, Celts occupying the western part of Europe.

The Celts in Gaul

In the 4th century BC. J.-C., the Celts continue their conquest of the Rhone Valley and attack Marseille. The city faces the invasion in order not to lose its independence. At the same time, the Allobroges settled in the north of Isère, the Voconces in the north of Ventoux, the Tricastins in the Drôme valley, the Cavares between Valence and Avignon, the Arécomices of Orange in Narbonne and the Tectosages of Narbonne to Toulouse. According to the sources, a certain Ambigat, king of the Bituriges (Bourges), would have dominated most of the peoples of central Gaul.

Settled in southern Gaul, the Celts developed there a "civilization of the oppida", like that of Ensérune, near Béziers, or Entremont (north of 'Aix en Provence). They helped to animate the exchanges both towards the north, along the Rhône, and towards the west, along the Garonne, towards Carcassonne, Toulouse, and even the Atlantic, by which the tin coming from the future England.

Economic activity

During the period from around 1000 to 600 BC, i.e. during most of the "Hallstatt civilization", the economy remained close to subsistence level, except for the warrior aristocracy. But the latter only exercised its power over communities that were probably few in number, and only reigned over small areas (five to ten kilometers around the center). Trade was then mainly present around an east-west axis, which connected the German mining areas supplying copper and tin and the western regions using these ores to manufacture bronze objects.

But from the beginning of the 6th century BC, the foundation of Marseilles by the Phocaean Greeks and the development of the Provençal hinterland led to the creation of a new north-south commercial axis destined to take on great importance. Many products of Greek, Marseilles or Etruscan origin, having borrowed the Rhône furrow and the passes of the Alps, will be found in Gaul and in Northern and Western Europe:wine, gold and silver, bronze and ivory objects, jewelry, weapons .... Raw materials and semi-processed objects were transported from the North to the South (wood, metals, resin, pitch, amber, salt, wool, skins...); the North also provided mercenaries and slaves.

But from the beginning of the 6th century BC, the foundation of Marseilles by the Phocaean Greeks and the development of the Provençal hinterland led to the creation of a new north-south commercial axis destined to take on great importance. Many products of Greek, Marseilles or Etruscan origin, having borrowed the Rhône furrow and the passes of the Alps, will be found in Gaul and in Northern and Western Europe:wine, gold and silver, bronze and ivory objects, jewelry, weapons .... Raw materials and semi-processed objects were transported from the North to the South (wood, metals, resin, pitch, amber, salt, wool, skins...); the North also provided mercenaries and slaves.

These facts explain the decline of the Hallstatt civilization, but we must also take into account the aggressive southward movement of the La Tène Celts, who had more preserved their warrior tradition . The slowdown in trade was in fact added to several other factors:demographic pressure, less favorable climatic conditions, reduction in food resources.

Celtic Art and the Tomb of Vix

Four styles are observed during the Hallstatt and La Tène periods. During the first civilization, the Celtic style uses geometric and abstract ornamental forms. The main source of inspiration is nature and more specifically plants. The Greek and Etruscan inspiration is observable, notably in the use of Greek foliage, but there is no figuration. Art is present mainly on objects of a certain value:sword scabbards, jewelry, cups, etc.

The continuous vegetal style derives from the first style and is no longer influenced by the Mediterranean style in the 4th century BC. The use of two-dimensional plant motifs, with a less geometric look, characterizes the new style. Enamelware and glassware develop. In the third century BC. J.-C., the plastic style uses the geometric volumes which allow them, by combinations, to make appear figures. The style of swords, which developed at the same time as the plastic style, used incised plant motifs, inspired by the plant style, to decorate, among other things, pieces of weaponry.

The continuous vegetal style derives from the first style and is no longer influenced by the Mediterranean style in the 4th century BC. The use of two-dimensional plant motifs, with a less geometric look, characterizes the new style. Enamelware and glassware develop. In the third century BC. J.-C., the plastic style uses the geometric volumes which allow them, by combinations, to make appear figures. The style of swords, which developed at the same time as the plastic style, used incised plant motifs, inspired by the plant style, to decorate, among other things, pieces of weaponry.

The tomb of Vix was discovered in 1953 in Burgundy near Mont Lassois, the site of one of the great princely residences of the civilization of Hallstatt. Located in the heart of a vast funerary complex made up of a dozen necropolises, the tomb of Vix is the richest and testifies to the care the Celts took to honor their most illustrious dead.

Dating from the 5th century BC, this tomb, probably that of a princess, is indicative of the wealth of the aristocracy which also controlled merchant activity:the deceased wore a gold diadem, an amber bead necklace, a bronze torque and bracelets; the burial chamber also contained a dismantled chariot, a Greek bronze vase 1.65 meters high and other bronze objects of Etruscan origin. The currents of exchange therefore linked the heart of Gaul and the Mediterranean world several centuries before the Roman conquest.

Religion of the Celts and role of the Druids

Originally, the Celts worshiped the sun, mountains, forests and rivers. They worship as many deities as they know of springs, fountains, forests, etc. According to the tribes, the Celts can venerate the same god under different names, or different gods.

Celtic gods are honored through rites, presided over by Druids. In this society where everything is based on the sacred, the druids have a considerable role. They can be classified into three groups:the bards, who sing hymns and poems; the vates, who are soothsayers; and the theologian druids, sages and scholars, first in importance and dignity, often descended from the nobility.

Celtic gods are honored through rites, presided over by Druids. In this society where everything is based on the sacred, the druids have a considerable role. They can be classified into three groups:the bards, who sing hymns and poems; the vates, who are soothsayers; and the theologian druids, sages and scholars, first in importance and dignity, often descended from the nobility.

Druids are very influential sages and advisors to the king. They are judges, Celtic law being considered of divine origin. They practice medicine and astronomy, and we owe them, for example, a lunar calendar and units of measurement such as the league (measure of length) or the arpent (agrarian measurement).

Druids are also teachers who transmit knowledge orally. Indeed, the writing, which uses the Greek alphabet, is of exceptional use:for commercial accounts, currency, engravings of funerary stelae or magic.

Celtic Gaul

One thing is obvious:Gaul has no political unity. It consists of tribes ruled by potentates and more powerful peoples ruled by nobility. The most important are the Aedui, Arvernes, Bituriges, Carnutes, Séquanes, Remes, Vénètes, Pedestrians, Santons, Lémovices, Trevires and Helvetii, all gathered in central Gaul. They formed themselves into states bringing together different civitas. From the 2nd century BC. J.-C., the civitas represents a people recognized by a common ethnic origin and by a region of variable surface. Then, each people is divided into tribes. In each of these tribes is a set of families linked together by the same lineage. The area of a civitas is different from one group to another.

Until the 5th century, continental Celtic languages, including Gaulish, were spoken in Western Europe (Gaul, Hispania, northern Italy), but their importance declined under the influence of Latin, and little is known about them.

Around the 2nd century BC. J.-C., the Celtic peoples stop their migration in various parts of Europe. In Gaul, they built their first cities, the oppidums. Some cities result from the transformation or displacement of a village. Others are founded in a place where no agglomeration existed before. The foundation and development of these settlements are generally attributed to two events:the invasion of the Cimbri and the Teutons in Gaul towards the end of the 2nd century BC. J.-C., on the one hand, and the creation of the Roman province of Narbonnaise, on the other hand. The first amplified the need for protection. The second allowed the Gauls to observe Roman cities before reproducing them. We know today, thanks to in-depth archaeological excavations, that the creation and development of these cities respond to profound changes in Gallic society.

The Romans come to Gaul

The Romans come to Gaul

The Romans entered the scene as early as 125 BC. AD by helping Marseille to defend itself against the coalition of Gauls and Ligurians. The following year, the consul Sextius Calvinus seized Entremont and founded the nearby Roman colony of Aquæ Sextiæ (Aix-en-Provence), and two years later, the Roman army defeated the Allobroges, the people the most powerful Gaul on the left bank of the Rhône.

The Arvernes, who had come to help the Allobroges, were also beaten and the Romans annexed a new territory comprising the Rhone Valley as far as Vienne and Geneva, the entire southern slope of the Cévennes as far as in the Tarn and to the west the Garonne valley to the outskirts of Agen. This resulted in the creation of the first Roman province in Gaul:the Provincia, in 120 BC. J.- C. From this moment, many commercial relations are established between Romans and Gauls.

Roman interference in Gaul became more and more pressing, until a certain Julius Caesar decided to conquer it in 58 BC. Caught between the Romans and the Germanic peoples, the Celtic world faded little by little, remaining with its language only on the Atlantic borders of Europe, in the British Isles (Wales, Scotland, Ireland) and in Brittany.

Bibliography

- The Celts in Europe, by Maurice Meuleau. Editions Ouest-France, 2018.

- Reinventing the Celts, by Katherine Gruel and Olivier Buchsenschutz. Hermann, 2019.

- The Celts, Celtic Gaul:A Critical Study, by Lucien De Valroger. Nabu, 2010.

- The Politics of the Gauls:Political Life and Institutions in Hairy Gaul, by Emmanuel Arbabe. Editions de la Sorbonne, 2018.