The Eusébio de Queirós Law (Law No. 581), enacted on September 4, 1850, prohibited the slave trade.

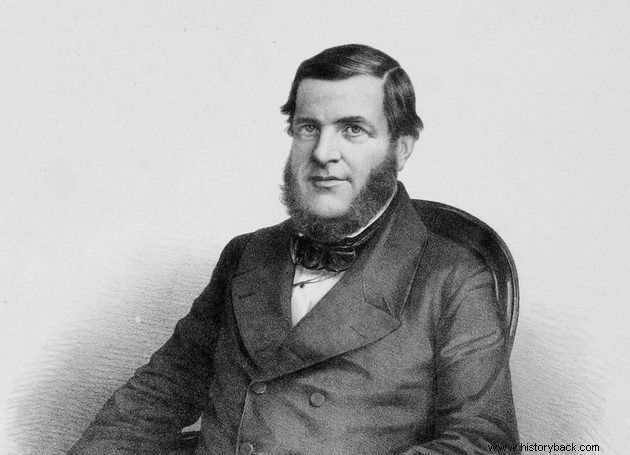

The law was drafted by the Minister of Justice, Eusébio de Queirós Coutinho Matoso da Câmara (1812-1868), during the Second Reign.

It was the first of three laws that would gradually abolish slavery in Brazil.

Afraid of the reprisals that could come through the Bill Alberdeen Act (1845), the Minister of Justice introduced a bill for the extinction of the slave trade.

Many Brazilian planters, especially in the northeast, had mortgaged their land in order to pay off debts to slave traders. Several of these loans were contracted with the Portuguese and there was a risk that the land would pass back into Portuguese hands.

Eusébio de Queirós still argued that, with the entry of more and more enslaved blacks, there could be an imbalance between free and slave people. This could lead to episodes of revolt led by blacks such as Haiti's Independence or the Malê Revolt.

Consequences of the Eusébio Queirós Law

The Eusébio de Queirós Law provoked a reaction from Brazilian elites against the imperial government.

Two weeks later, on September 18, 1850, the Senate passes the Land Act. This guarantee the property to whoever had a title registered in a notary's office, that is, to those who could buy it.

Thus, farmers could lose a movable asset (the enslaved people), but they had secured their real estate (the land). Likewise, the price of the slave rose and the internal traffic increased.

The Eusébio de Queiros Law was only really enforced when the Nabuco de Araújo Law (nº 731) came into force in 1854. Enacted on June 5, 1854, this law was a complement to the previous one.

This law established who would be held responsible and who would judge the person accused of trafficking. It also eliminated the need to be caught in the act to denounce those who committed this crime.

Abolition of Slavery in Brazil

Since the arrival of the Portuguese court, in 1808, to their colony in America, the English pressured the Portuguese crown to end the slave trade.

In 1845, England, through the Bill Aberdeen Act (1845) prohibited the slave trade between Africa and America. It also authorized the British to seize intercontinental slave ships.

England was interested in the end of slavery, as it had abolished slave labor in its colonies and knew that the use of slave labor made products cheaper. Therefore, in order to avoid competition from the Portuguese colonies, he began to take measures that put an end to the slave trade throughout the world.

King Dom João VI (1767-1826) knew he would face problems on both sides of the Atlantic if he abolished slave labor.

The Brazilian elite, fearful of losing this source of profit, supported Independence when they assured that this privilege would continue and so after the 7th of September 1822 little or nothing was done. In the Second Reign, in order not to contradict the rural aristocracy, slavery would be abolished gradually and without compensation.

It wasn't until 1888, however, that this work actually became prohibited, after 300 years of slavery.

Slavery in Brazil

Slavery in Brazil represented one of the most terrible times in the country's history. Until today, the descendants of slaves, mulattos (black and white), cafuzos (blacks and Indians), suffer from the reflection of 300 years of slavery in the country.

When the Portuguese established a colony in America, they enslaved and killed many Indians. In turn, blacks were brought in as slaves, as the sale of human beings was practically the only economic activity in the territories of Portuguese Africa.

During the colonial period, blacks largely represented the workforce used by the Portuguese. Effectively, they were the ones who made the economy of the colony and the metropolis turn.

Hundreds of Africans were transported on slave ships from Africa in subhuman conditions and sold in the country's ports to farmers. They would have to work in a regime of violence and grueling hours.

However, in the reign of Dom Pedro II (1825-1891), the situation had changed. The European continent was undergoing the transformation resulting from the Industrial Revolution that generated the emptying of the countryside and unemployment in the city, causing people to immigrate.

Likewise, the unification processes of Italy and Germany left thousands of people without land and the best solution was to immigrate.

The abolitionist movement, which emerged in the country in the second half of the 19th century, was the propeller of anti-slavery ideals and contributed to the end of slave labor.

The farmers also, in a clear racist posture, preferred the labor that arrived from Europe than paying a salary to the ex-slave.

Thus, when the Lei Áurea definitively freed the slaves, on May 13, 1888, the country was not prepared for the inclusion of such people, who were mostly marginalized.

During the Republic, there was also no social inclusion project. On the contrary:manifestations such as music, dance or religion were controlled and persecuted by the police.

See also:Abolition of Slavery in BrazilAbolitionist Laws

In addition to the Eusébio de Queirós Law, two laws contributed to the gradual liberation of commerce and slave labor in Brazil:

- The Free Womb Law (1871), the first signed by Princess Isabel, granted freedom to children born to slave mothers from that date onwards.

- The Sexagenarian Law, enacted in 1885, guaranteed freedom for slaves over 60 years old.

The enslaved would be freed, definitively, by the Golden Law, signed by Princess Isabel, on May 13, 1888.

We have more text on the subject for you:

- Slave Traffic

- Black Brazilian Personalities