Bolognesi was a great patriot. He has the characteristic of superior men. No intemperate words or puerile bravado come from his mouth or from his pen. He is cultured and attentive to the enemy. When patriotism is wrapped in a cloak of modesty, the man disappears before the idea that encourages him and his sacrifice takes on an impersonal character. This is how it happened to Grau and it will happen to Bolognesi. Bolognesi did not know in the first moments what happened in the Campo de la Alianza. The day of the fight he felt the cannonade. He saw columns of smoke appear in the distance, in the blue sky, but he couldn't figure out what was happening. The telegraph to Tacna was cut. No emissary came from the Montero field to tell him anything. Some dispersed came later; the natives of Arica who were returning to their homes, fleeing from defeat, but as common soldiers they did not understand what had happened and, repeating what was circulating in Tacna on their way out, they said that Montero had withdrawn to Pachia with a considerable part of the army and that Leiva with the forces of Arequipa he threatened the Chileans by Sama. Bolognesi, under this false impression, which was the same that Vergara had picked up in Tacna, telegraphed to the Prefect of Arequipa by cable to Mollendo, telling him:

“May 28. I know that Montero has an important part of the army left, and the purpose of this is to tell him that Arica will resist until the last.”

Francisco Bolognesi Other telegraphic communication:

Francisco Bolognesi Other telegraphic communication: “May 28. If the enemy is besieged from Sama or Pachia, I think they save Arica and Tacna. Everything ready here to fight.”

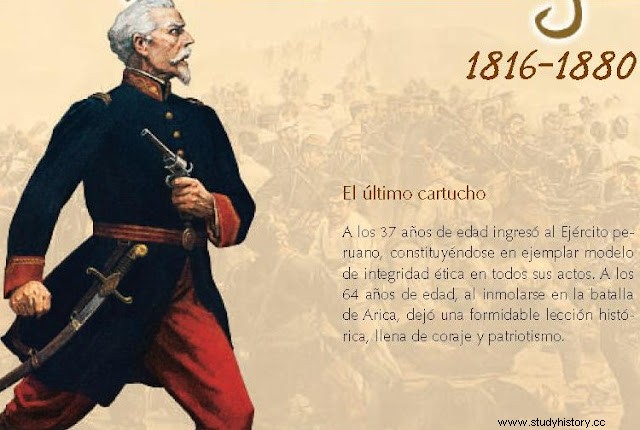

The Chilean cannons were placed very far away for fear of being bombarded by the long-range pieces of the plaza, and the Arica garrison, in view of the ineffectiveness of those shots, lost prestige due to the enemy artillery, and conceived hopes that until then had not entertained. The plaza was under this impression when Baquedano dispatched, as an emissary, to request their surrender from the artillery commander, Salvo. He was received decorously, blindfolded, and led into the presence of an old man with a white beard who treated him with dignity. It was Bolognese. He informed him of the commission that brought him before him; Bolognesi replied that the defenders of Arica were determined to perish rather than surrender. And to give more authority to his word, he called the main chiefs and renewed his statement in front of them.Immediately he telegraphed his government through the Prefect of Arequipa.

“June 5. Enemy parliament intimates surrender. I answer, prior agreement, bosses:we will resist until the last cartridge is burned.”

On the afternoon of the 6th, when the bombardment was over, Lagos sent Elmore to ask Bolognesi for the last time to surrender the square and to warn him that he would not be able to answer for his soldiers if the mines exploded. The emissary was well chosen, because he could speak the language of truth, saying what he had seen, and make considerations that were forbidden to a Chilean parliamentarian. It is almost certain that Elmore would explain to Bolognesi the decisive effect of the combat at Tacna, and the strength that the victor retained. Perhaps it meant that he had to abandon the blind trust he placed in the mines because the Chilean General Headquarters had seized the connection plan for the wires by apprehending him. These are assumptions, albeit very plausible. What is known about that conference is that Elmore recorded in writing that his mission was to ask for capitulation, to which the besieged responded as follows:“You can go back and say that notwithstanding the answer given to the official parliamentarian, Mr. Salvo, we are not far from listening to the worthy propositions that can be made officially, fulfilling the prescriptions of war and honor.”

The bodies remained that way until dawn on the 7th. At midnight Lagos had two officers of the General Staff would secretly cover the terrain that separated the regiments from their objectives so that when the time came they would serve as guides. Those officers were the captains don Belisario Campos and don Enrique Munizaga. When the semi-clarity of the first morning light began to dissipate the mist from the coast, each regiment left its camp crouching, taking infinite precautions not to be seen or felt, guided by those officers, distributed in companies separated from each other by a distance of fifty meters. Each regiment consisted of two battalions. The forward companies of the 3rd were those of the captains don Pedro A. Urzua and don Leandro Fredes. The first battalion of the 4th was commanded by Commander Don Juan José San Martín; the 2nd, Commander Don Luis Solo Zaldívar. The first battalion of the 3rd, Colonel Don Ricardo Castro; the second, Commander Don José Antonio Gutiérrez.

The sentinels of the Citadel heard a rumor and fired. The square woke up to the rifle shots that drew culverins of light in the clear dark of the morning. Everyone ran to their post. The 3rd Regiment, seeing itself discovered, undertook the assault on the fort of Carrera, under a hail of bullets and reaching the walls of sacks, attacked them with their yataganes and knives. The sand ran through the holes, the tallest sacks collapsed and the soldiers jumping on them penetrated the mined area. The official part of the head of the Regiment number 3 records that the first to climb the Citadel and lower the enemy flag was Second Lieutenant Don José Ignacio López. The human avalanche penetrated that enclosure and the duel of assailants and assailants continued at close range inside the narrow square surrounded by the sand from the bags that had been emptied.

What was Bolognesi doing?

Bolognesi had believed that the enemy would initiate his attack through the forts of the lower area, deceived by the already known stratagem and, as I stated, in that concept he had sent Ugarte's division on the 6th in the afternoon to protect them. That division consisted of 600 men or so. It was made up of the Tarapacá battalions commanded by Zavala and the Iquique, by Sáenz Peña. Once the fire broke out in the Citadel, Bolognesi arranged for Ugarte to return quickly to the attacked forts by climbing a muleteer road that connected the Morro with the town of Arica, but since the Chilean advance was so impetuous and fast, he did not manage to reach the high but half of the division, and the other was cut by the attackers, who, owners of the top, swept with their fires the rough path that the Peruvians followed. Those who managed to climb up joined the fugitives from the forts at the entrance to the Morro.

When the soldiers of the 3rd entered the Citadel enclosure, the ground cracked with two formidable dynamite explosions that sent flying through the air part of the occupants and raised a cloud of stones, heads, arms, legs that covered the air. A lieutenant of the 3rd Don Ramón T. Arriagada, thrown by the explosion to a height of seven or eight meters, fell unharmed, but completely naked and deaf, from which he was never cured. The second lieutenant of number 3, Mr. José Miguel Poblete, he severed his head, leaving the throbbing trunk on the ground. Many other horrible scenes caused the traitorous outburst. But the gap between the sacks was open and the assailants rushed through it and when they heard the explosion of the dynamite and saw its terrible effects, they rushed like wild beasts against the defenders of the enclosure and put them to the sword. The ground was covered with coagulated blood. In vain the chiefs ordered the horns to play "cease fire". No one heard the voice of mercy. Commander Gutiérrez said:the chiefs and officers were hoarse from shouting. Among the victims was Colonel Arias. The fort was taken.

The same thing happened in the eastern castle. A similar scene unfolded here. The march of the 4th Regiment was felt and the garrison led by Colonel Inclán opened fire against it. The Chilean troop undertook the assault on the run, leaving many dead and wounded. Arriving at the foot of the trench, he broke the sacks with his knives and, jumping over the collapsed wall, entered the fortress. The Peruvian resistance was less here than in the Citadel. The garnish was also smaller. In minutes the assailants had collapsed the sand walls and entered the enclosure, which was empty, because the Peruvians withdrew to the redoubts of Cerro Gordo that protected the entrance to the Morro. Inclán died defending his position. Let's separate ourselves for a moment from the battlefield of the high ground and see what was happening in the castles on the seashore. Their main defense, which was Ugarte's division, was no longer there. As I have said, it had been called by Bolognesi to help El Morro and those forts had nothing but their crew of artillerymen. When the combat of the high was advanced, the Lautaro arrived to them, deployed in guerrillas, led by Colonel Barboza.

The Peruvian garrison did not try to resist or rather its resistance was very weak. This is what the official parts of Barboza and the head of the body say. Commander Robles, and it is attested to by the fact that the 110th Regiment had but eight wounded. The Peruvian chief blew up the cannons with dynamite and the garrison fled towards the town where he was cornered, along with the soldiers of Ugarte's division who were unable to climb the Morro. The forts of the square, the Citadel and the East were in the hands of the Chileans. The Morro and its Cerro Gordo defenses were missing. When the soldiers of the 4th Regiment took possession of the walled enclosure of the East Fort, a cry was heard, which is not known who gave it or where it came from:to the Morro, boys! The troop, forgetting the order received, which was to wait for the Buin, rushed down the fortified path that led to that point, being joined on the way by soldiers of the 3rd who at that time were triumphing over the resistance of the Citadel. The ground was strewn with automatic mines and as the soldiers advanced, they took care to jump over the points where it was obvious that the ground had been removed for fear of stepping on a cap. Thus they reached the first trenches placed on elevation, having passed the wavy line that preceded them under fire, in the midst of a hail of bullets, and now with their rifles, now with the bayonet they forced them all, one after another, and Thus, walking over corpses and wounded, they reached the gates of Morro, in whose square the last flag of Peru waved.

Romantic version of Alfonso Ugarte's sacrifice In the flat space that crowned the hill were the survivors of the trenches and castles, the Morro garrison, and all the great reputations of Arica:Bolognesi, Moore, Ugarte, Sáenz Peña, Blondel. The assailants invaded the compound in a hectic and vertiginous race, mixing the officers with the soldiers. Commander San Martín had been mortally wounded on the way from Cerro Gordo to Morro. The glorious regiment was now commanded by Solo Saldívar. Seeing the Morro square invaded, Bolognesi ordered the fires to be suspended. He understood that resistance was impossible, and it should have been said that his duty was done. I do not want this assertion, which offends the Peruvian legend of the defense of Arica, to rest on my word. The commander of the batteries officially says so. Colonel Espinosa, in the report of the action, addressed to the Chief of the Peruvian General Staff:"Meanwhile, the troops that had their rifles in a state of service continued to fire in retreat, until the enemies invaded the compound (of Morro) making volleys on the few that were left there. In this situation, Colonel Don Francisco Bolognesi, Chief of the plaza, arrived at the battery; Colonel Don Alfonso Ugarte; Lieutenant Colonel Don Roque Sáenz Peña, who was wounded; Sergeant Major Don Armando Blondel, and others that I do not remember, and since all resistance was now useless, the General Commander ordered that the fires be suspended, which could not be achieved by voice, but Colonel Ugarte personally ordered it to those who were shooting their weapons to the other side of the barracks, where said chief was killed. At the same time that these events were taking place, the enemy troops were firing their weapons at us, and Messrs. Colonel Bolognesi, Captain Moore, Lieutenant Colonel Sáenz Peña, the undersigned, and some officers of this battery found us gathered together, and despite If the fires had been suspended on our part, they fired at us from which the General Commander, Colonel Don Francisco Bolognesi and commander of this battery, Mr. Captain of the ship, Don Juan Moore, were killed, the others having been saved by the presence of officers who they took prisoners.”

Romantic version of Alfonso Ugarte's sacrifice In the flat space that crowned the hill were the survivors of the trenches and castles, the Morro garrison, and all the great reputations of Arica:Bolognesi, Moore, Ugarte, Sáenz Peña, Blondel. The assailants invaded the compound in a hectic and vertiginous race, mixing the officers with the soldiers. Commander San Martín had been mortally wounded on the way from Cerro Gordo to Morro. The glorious regiment was now commanded by Solo Saldívar. Seeing the Morro square invaded, Bolognesi ordered the fires to be suspended. He understood that resistance was impossible, and it should have been said that his duty was done. I do not want this assertion, which offends the Peruvian legend of the defense of Arica, to rest on my word. The commander of the batteries officially says so. Colonel Espinosa, in the report of the action, addressed to the Chief of the Peruvian General Staff:"Meanwhile, the troops that had their rifles in a state of service continued to fire in retreat, until the enemies invaded the compound (of Morro) making volleys on the few that were left there. In this situation, Colonel Don Francisco Bolognesi, Chief of the plaza, arrived at the battery; Colonel Don Alfonso Ugarte; Lieutenant Colonel Don Roque Sáenz Peña, who was wounded; Sergeant Major Don Armando Blondel, and others that I do not remember, and since all resistance was now useless, the General Commander ordered that the fires be suspended, which could not be achieved by voice, but Colonel Ugarte personally ordered it to those who were shooting their weapons to the other side of the barracks, where said chief was killed. At the same time that these events were taking place, the enemy troops were firing their weapons at us, and Messrs. Colonel Bolognesi, Captain Moore, Lieutenant Colonel Sáenz Peña, the undersigned, and some officers of this battery found us gathered together, and despite If the fires had been suspended on our part, they fired at us from which the General Commander, Colonel Don Francisco Bolognesi and commander of this battery, Mr. Captain of the ship, Don Juan Moore, were killed, the others having been saved by the presence of officers who they took prisoners.”The Chilean army has been accused of inhuman cruelty, extending it to the chiefs, supposing that the massacre of Fort Ciudadela and that of the Morro chiefs was due to a slogan or order of the day not to take prisoners . What happened there is solely attributable to the disorderly nature of the attack and the excitement of the dynamite. But if there is an explanation for this, impartial history does not have one for the inhumane shooting of some Peruvian soldiers cornered in the small square of the Arica church, belonging to that troop from Iquique and Tarapacá that did not manage to climb the Morro and locked themselves up in that place. It has never been known who gave such an order or if the soldiers acted on their own, enraged as they were by the explosion of the mines. The time to quench passions has passed long enough for both Peru and Chile to pay just tribute of admiration to winners and losers. And just as the memory of this marvelous feat will always be a stamp of pride for Chileans, it is an honorable action for the defenders of the plaza, who fought to give Peru a tradition and an example. Bolognesi, Moore, Ugarte, Blondel were the last defenders of their country in the department of Moquegua and they fought on the last piece of land that they were allowed to set foot on. The enemy lost between 700 and 750 men that day, and the Chileans, between dead and wounded, 473. The Peruvian prisoners were 1,328, including 18 chiefs and officers.

“War of the Pacific from Tarapacá to Lima ”. Published in 1914 in Valparaíso. Pages 362, 363, 369, 370, 372, 380-388.