Mochica priests carry cups with the blood of sacrificed prisoners. Cool. National Museum of Archeology and History of Peru, Lima. The Mochicas were also excellent craftsmen, producing pottery of extraordinary beauty and perfection, as well as delicate gold, silver, and copper ornaments for their leaders. They also established extensive and prosperous commercial networks that extended into the current territories of Chile and Ecuador. But towards the end of the eighth century, this sophisticated and rich culture met a sudden end. A series of natural cataclysms, caused by drastic climate change, affected the coastal area where the Mochica society had developed and contributed to its disappearance.

Mochica priests carry cups with the blood of sacrificed prisoners. Cool. National Museum of Archeology and History of Peru, Lima. The Mochicas were also excellent craftsmen, producing pottery of extraordinary beauty and perfection, as well as delicate gold, silver, and copper ornaments for their leaders. They also established extensive and prosperous commercial networks that extended into the current territories of Chile and Ecuador. But towards the end of the eighth century, this sophisticated and rich culture met a sudden end. A series of natural cataclysms, caused by drastic climate change, affected the coastal area where the Mochica society had developed and contributed to its disappearance.Control of the territory In the north, the Mochicas had spread through the Jetepeque River valley, whose main settlements were San José de Moro and Huaca Dos Cabezas, and through the Lambayeque River valley, where Sipán and Pampa Grande are located. This northern culture stood out in the development of copper metallurgy, of which magnificent examples have been found in some tombs of rulers, such as the famous tomb of the Lord of Sipán, discovered in 1987 by the Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva, and which provided a spectacular treasure of precious metal pieces of great beauty. The Mochicas knew the techniques of rolling, gilding, embossing, and casting, and they mastered metal alloys. They used gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, and even mercury. In the south, the Mochicas occupied the valley of the Moche River, where the Huaca del Sol and the Huaca de la Luna are located, and the valley of the Chicama River, where the ceremonial complex of El Brujo is located. The southern Mochicas stood out for their mastery of pottery techniques, since while in the north the ceramic forms are simpler, in cream and red colors, most of the animal-shaped ceramics made by this people have been found in this area. . Both the south and the north are areas of great aridity, and the Mochicas had to overcome the desert through artificial irrigation. They diverted water from the rivers that flow down from the Andes and, using mud bricks, created an extensive system of aqueducts, many of which are still in use. In this way they developed an agriculture, with more than thirty crop varieties, which allowed them to have a wide range of agricultural surpluses. They also extensively exploited marine resources, of which the Pacific Ocean provided them in abundance, as well as hunting.

A very hierarchical society The Mochicas settled in urban centers that constituted the center of small states with a highly hierarchical social structure. The main nucleus of these States were the huacas. The sovereign, who received the title of cie-quich, belonged to the military nobility and played an important role in the rituals that took place in the huacas. His life was completely dedicated to war, to religious rites in honor of the main Mochica divinity, Ai Apaec, and to enhancing his prestige against rival leaders. Below the great lords were the priests, guardians of knowledge. astronomical, architectural and metallurgical, and that they could also cure diseases. At a lower level were the artisans, the merchants and the common people, made up of peasants, fishermen and soldiers. Slaves, normally prisoners of war, formed the bottom rung of Mochica society. In the 6th century, this society intimately rooted in its physical environment began to feel the ravages of a meteorological phenomenon known as El Niño:a warm ocean current prevents the upwelling of the colder waters of the Humboldt Current, which favors the evaporation of seawater, which then falls in the form of torrential precipitation. El Niño affects this area regularly, but at the time it was unusually strong and prolonged:intense and endless rains ravaged the region for thirty years.

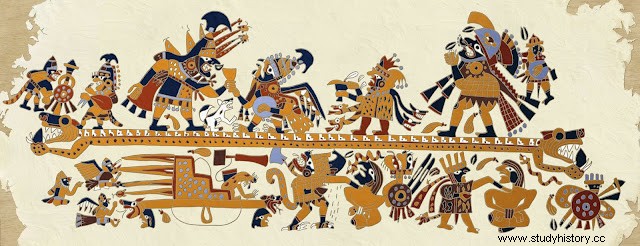

The Mochica ritual sacrifice of prisoners is represented on countless ceramics and painted reliefs in the huacas. In the scene reproduced here, four characters of high social position preside over the ceremony. Below, high-ranking warriors sacrifice those who have lost the ritual combat. The devastating El Nino The downpours destroyed palaces and pyramids, built with mud and therefore very vulnerable to the dissolving action of the water. The rivers burst their banks and the mud swept away both large tracts of arable land and small towns built with adobe and cane, drowning their inhabitants. These terrible floods contaminated water courses and springs, and eroded thousands of hectares of arable land. Typhoid fever and other epidemics were rampant, sowing death and destruction. Such intense and devastating rainfall was followed by a three-decade cycle of drought, which between 563 and 594 drastically reduced the number of mountain springs that reached the coast. This was catastrophic for agriculture, with consequent famine, and caused increasing desertification that caused the sand dunes to engulf numerous settlements. In the year 602 the torrential rains returned, and between 636 and 645 the drought struck again with force the region. Miles of canals remained dry and filled with sand, crops died, and food supplies were depleted. El Niño also caused a change in sea currents that reduced fish catches, especially anchovies, which were an essential part of the coastal diet and an important item of trade. In this way, the bankruptcy of agriculture was followed by the ruin of fishing, with which the last food resource of the Mochica disappeared. As a result of all this, thousands of people died of hunger.

The Mochica ritual sacrifice of prisoners is represented on countless ceramics and painted reliefs in the huacas. In the scene reproduced here, four characters of high social position preside over the ceremony. Below, high-ranking warriors sacrifice those who have lost the ritual combat. The devastating El Nino The downpours destroyed palaces and pyramids, built with mud and therefore very vulnerable to the dissolving action of the water. The rivers burst their banks and the mud swept away both large tracts of arable land and small towns built with adobe and cane, drowning their inhabitants. These terrible floods contaminated water courses and springs, and eroded thousands of hectares of arable land. Typhoid fever and other epidemics were rampant, sowing death and destruction. Such intense and devastating rainfall was followed by a three-decade cycle of drought, which between 563 and 594 drastically reduced the number of mountain springs that reached the coast. This was catastrophic for agriculture, with consequent famine, and caused increasing desertification that caused the sand dunes to engulf numerous settlements. In the year 602 the torrential rains returned, and between 636 and 645 the drought struck again with force the region. Miles of canals remained dry and filled with sand, crops died, and food supplies were depleted. El Niño also caused a change in sea currents that reduced fish catches, especially anchovies, which were an essential part of the coastal diet and an important item of trade. In this way, the bankruptcy of agriculture was followed by the ruin of fishing, with which the last food resource of the Mochica disappeared. As a result of all this, thousands of people died of hunger.The collapse of society This situation caused a considerable upheaval in Mochica economic and social life, to the point that on many occasions their leaders had to abandon their political, religious and administrative centers due to the destruction caused by these drastic climatic changes. Archaeologists, for example, have discovered that the rainfall that fell in the Sipán area forced its leaders to move to the neighboring settlement of Pampa Grande to continue controlling the Lambayeque Valley from there. The lords of Cerro Blanco also had to leave the place to move to the settlement of Galindo, located in the strategic gorge of the Moche River. From Galindo, which became the largest center in the area, the Mochica chieftains could control the irrigation systems and access to the fertile lands of the Moche River valley. The people settled with their lords to be as close as possible to water sources and avoid the dunes that threatened crops and towns downstream. This catastrophic series of climatic factors seriously weakened the Mochica institutions. The nobility, away from the day-to-day of their subjects, lived busy in their dynastic disputes and ritual ceremonies. But the people blamed their rulers for the chaotic situation and for having fallen out of favor with the gods. Consequently, the hierarchs increased human sacrifices to win divine favor, without success. However, the rich grave goods found in the tomb of a priestess, in San José de Moro, dated around the year 720, show that the Mochica elite he was reluctant to give up his ancestral privileges, even though this type of burial meant a huge expense for a society punished by the climate and weakened by the scarcity of food and resources. At Huaca de la Luna, archaeologists unearthed the remains of some seventy men who had been sacrificed and dismembered in the course of at least five ritual ceremonies. They were victims of a rite designed to placate the powerful forces of nature.

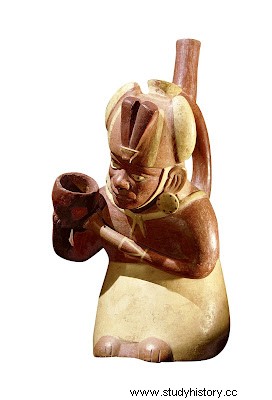

Mochica pottery depicting a Mochica priest performing a libation. British Museum, London Final Collapse At the end of the 7th century, the rains caused by an extremely intense Niño devastated many irrigation systems near Pampa Grande and Galindo. Consequently, both centers were abandoned around the year 750 and the population was grouped independently, which meant the collapse of the Mochica political system. A civil war may even have broken out:archeology shows that the Mochica, after abandoning their old settlements, created new ones, where the huge huacas of yesteryear were replaced by fortresses. Having lost authority and control over their people, the chiefs Mochicas fought each other in a fierce struggle for control of the scarce resources that remained in the area. The last Mochica settlements, governed by a worn-out ruling class, could not avoid falling into the hands of the emerging Huari (or Wari) State, an overwhelming military machine that conquered most of the coastal and highland lordships of the central zone of the Peruvian Pacific. In the following three centuries, the Huari concentrated immense power, built enormous urban centers and built an authentic empire, something unprecedented until then in the history of Andean cultures.

Mochica pottery depicting a Mochica priest performing a libation. British Museum, London Final Collapse At the end of the 7th century, the rains caused by an extremely intense Niño devastated many irrigation systems near Pampa Grande and Galindo. Consequently, both centers were abandoned around the year 750 and the population was grouped independently, which meant the collapse of the Mochica political system. A civil war may even have broken out:archeology shows that the Mochica, after abandoning their old settlements, created new ones, where the huge huacas of yesteryear were replaced by fortresses. Having lost authority and control over their people, the chiefs Mochicas fought each other in a fierce struggle for control of the scarce resources that remained in the area. The last Mochica settlements, governed by a worn-out ruling class, could not avoid falling into the hands of the emerging Huari (or Wari) State, an overwhelming military machine that conquered most of the coastal and highland lordships of the central zone of the Peruvian Pacific. In the following three centuries, the Huari concentrated immense power, built enormous urban centers and built an authentic empire, something unprecedented until then in the history of Andean cultures.Source:http://www .nationalgeographic.com.es/history/great-reports/the-dramatic-end-of-the-mochica-civilization_6641/2

Learn more The current of El Niño and the fate of civilizations. Brian Fagan. Gedisa, Barcelona, 2010. Sipán, discovery and research. Walter Alba. Author's edition, Lambayeque, 2004.