"The Prohibited Books of 1821" are a collective work of three texts, which were written over a period of twenty-two years, from 1797 to 1819.

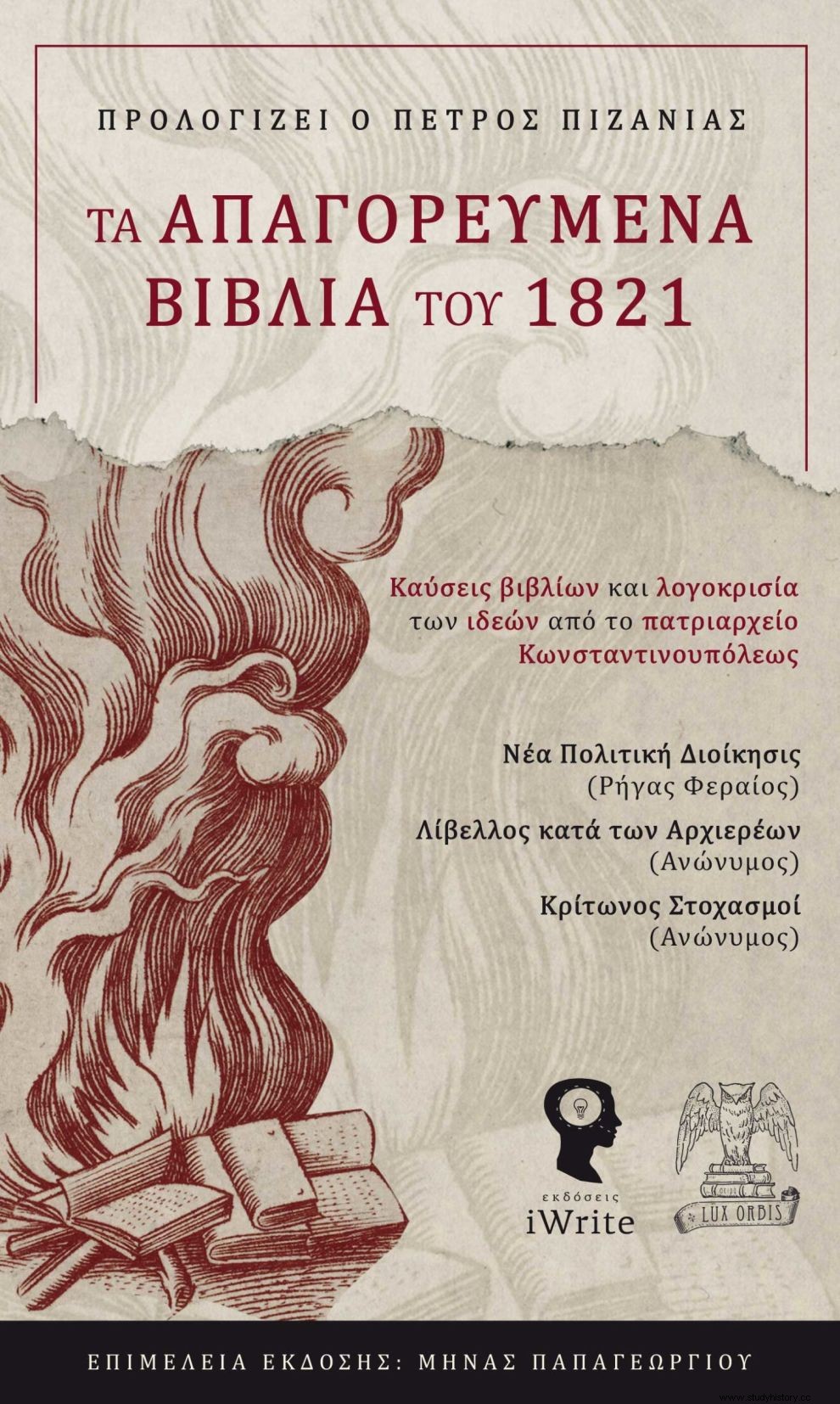

"New Political Administration" (Vienna, 1797) by Rigas Velestinlis, "Livellos against the High Priests", written by an anonymous author in Smyrna in 1810, and "Kritonos Stochasmos", also published by an anonymous author in Paris in 1819, are the three political texts that were written over a period of 20 or so years, and come to light today as a single publication (published by iWrite - Lux Orbis series), constituting a collective and particularly significant work, as far as pre-revolutionary Greek texts are concerned, of unknown bibliography.

The study of these three "forbidden" works, once again confirms the fact that the triptych Freedom, Knowledge and Right Reason, was treated pre-revolutionary with great hostility by the highest leadership of the Church, whose role and action are imperative to be re-evaluated from younger generations. Two of the three works were burned in the courtyard of the Patriarchate of Constantinople by order of the historically controversial, Gregory V, while the third almost disappeared from the face of the earth (about the burning of Riga's works before 1821 in Constantinople, you can read more in detail at "Black Book of 1821").

The new edition is prefaced by the renowned emeritus professor of History at the Ionian University, Petros Pizania, while at the end the epitome of Dr. of History, Athanasios Gallos, dedicated to the importance of the first edition of "Livellos" in Greek literature.

"The High Priests despised the common interest of the people, and they look to the same. They consolidated the state itself and despotism in the disease and ignorance of the people".

Libello against the High Priests (Anonymous, 1810)

Minas Papageorgiou, journalist and Director of the Lux Orbis Series of iWrite publications, speaking to the Magazine, stands out as a common element of these three works, the fact that they were so strongly targeted by the ecclesiastical Authorities of the time, precisely because of the dynamics they had.

What is the common thread that runs through the three texts presented here?

"New Political Administration" by Rigas Feraios, together with the works of anonymous authors "Libellus against the High Priests" and "Crito's Reflections", compose a seemingly disparate puzzle of texts in the new book of the Lux Orbis Series, entitled "The forbidden books of 1821 ". Different because (in order of quotation) the first work is a political manifesto for the future of the Balkan peoples outside the Ottoman empire, the second a complaint about the contribution of the Clergy to the spread of ignorance and superstition and the third a cry of despair for more Education, against phenomena of ecclesiastical corruption in Andrianoupolis.

Their common element is that all three of these texts were the target of ecclesiastical censorship during the pre-revolutionary period, since two of them (Riga's work and "Kritonos Stochasmi") were burned in the courtyard of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, while "Livellus "only one copy survives today. We understand, therefore, why they can be deservedly characterized as "forbidden" books.

In your opinion, what is the special significance of these texts for Greece in 2021?

These are works that bring us into direct contact with the social conditions that prepared the Greek Revolution. Riga's "New Political Administration" reflects the lust for Freedom . "Libellus against the High Priests" praises the Ortho Logos . For its part, "Kritonos Stochasmosi" presents the request for more Education , eves of the Race.

In this light, the foregoing reflects the problematic way in which the highest hierarchy of the Church pre-revolutionary dealt with these strongly emphasized concepts. Reading these texts (especially if combined with the "Black Book of 1821" that we released in March) conveys to the modern reader messages through which he can not only form a different image that he probably has of '21, but also contribute essentially in the public reflection on the quality of Education and the levels of Right Reason in Greek society today. What is happening around us demonstrates once again the huge cultural problem of our country.

Finally, a special mention deserves to be made of the reissue of "Livellos", two hundred and eleven years after its first release in Smyrna. Undoubtedly, this is a memorable publishing event, both for the specialist scholars of the New Greek Enlightenment, and for the readers-researchers who wish to come into contact with one of the most important anti-clerical texts of this period.

Trying to shed more light on the texts themselves but also on the era in which they were published, the Magazine spoke with Petros T. Pisania, emeritus professor of history at the Ionian University, who has edited the introduction to the publication.

In your estimation, could a pan-Balkan confederation of the time, if created, remove the ecclesiastical influence on the education system of the time and lead to a federal secular state on the ruins of the Ottoman empire?

Every science (except mathematics) investigates and ultimately clarifies a reality, physical or social. Therefore, the realm of scientific hypothesis follows this principle whether it is designing an experiment or researching historical records. So, in historical science too, there is no hypothetical question outside of historical reality except as a methodological and logical arbitrariness. The reason is that scientific knowledge is the only one of all forms of knowledge that is founded on evidence arising from the real facts examined. What evidence can be organized from something that never happened?

If today we can talk about a "Greek Enlightenment" or even an attempt to construct it, what are its main characteristics in terms of its specificity?

Let's skip the question first raised by E. Kant "What is Enlightenment" and investigated by M. Foucault. Historically, it is a particularly radical cultural movement with strong implications for questioning both the official worldview and the political ideology of the time. It was based on criticism which was practiced on the basis of right reason and materialistic philosophy.

The comparison of each particular Enlightenment movement, like the Greek one, is usually done with the French or more fragmentarily with certain great personalities, such as Newton or Locke. So their absence in ours creates doubts whether and to what extent there was a Greek Enlightenment. But, in the end, not only did it exist, but it was not an imported but an endogenous species that communicated with the European indirectly through texts and directly from the great dispersion of Greek intellectual enlighteners in European cities and universities for studies and less for teaching. The works of this New Hellenism social group consisted of educational actions which, although not particularly massive, were nevertheless very important against the three ecclesiastical obscurations (Orthodox, Armenian and Jewish) that prevailed in the Ottoman Balkans and elsewhere. Even the Greek enlighteners indulged in writing and publishing magazines and books which, as a product of the 18th century, shaped a space of secular rational thought and free expression in successful competition with the ecclesiastical and religious discourse that absolutely dominated for centuries. They also developed a dense debate about the Greek language, while the radical intellectual enlighteners cultivated a politicization against the Ottoman despotism, creating from many scattered old elements and scattered social practices a composite image of historical space and time which was condensed into the self-identification of "Greek". Of course, their contribution to the Friendly Society and subsequently to the Revolution was significant.

Would one say that in the action of Gregory V one finds the basic ideas of preservation that govern the entire post-revolutionary Greek history and reach up to the middle of the last century, or would such an assessment be an exaggeration?

I think that the action of Gregory V constitutes a very typical choice of a hierarch who, from his position, could only be an obscurantist and act as such (like many hierarchs in the other Orthodox patriarchates, in the Armenian one as well, even in the Jewish priesthood and of course in the Catholic Church). Let me remind you that the Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate, like that of Jerusalem, as well as the other Churches under Ottoman rule, through the privileges granted to them by the Sultans, constituted organic institutions exercising power and controlling their flocks on behalf of the Ottoman imperial state and in particular of the respective Sultan . And the execution of Gregory V was part of the practice of executions of high officials of the Ottoman state, Muslims or Christians without distinction, who had failed in the task assigned to them by the Sultan. The rather ridiculous thing about the official historiography of the Church is that they recruited Gregory V to the Friendly Society decades later, after the organization had ceased to exist and the Patriarch in question had been executed.

Finally, what constituted "modernity" in the first Greek state after the revolution of 1821?

The introduction of modern principles did not begin after '21 but from the first, almost, day of the Revolution with the handwritten regulations of the local revolutionary councils with which the Friends organized the first uprisings, starting from March 17, 1821. Then the regional revolutionary councils (Local polities) expanded them and finalized them in terms of fundamentals during the first National Assembly of Epidaurus. In the Third National Assembly with the Constitution of Troizena, the Greeks had very systematically finalized the government they wanted and implemented until then. It is about the establishment of the principle of Law against the despotic bureaucracy; the principle of the equality of all before the law instead of aristocratic privileges and local distinctions; the introduction of the People's polity (République) and of course popular sovereignty and political rights against servitude . And from the election of the first national political bodies, i.e. the Executive and the Parliament in January 1822, we have the minimal beginnings of creating a public administration, drawing up budgets, establishing a unified tax system, some rudimentary courts and of course elections to choose either the members of Parliamentary or representatives (national representatives) in national assemblies. We know from historical research that six electoral processes were held from 1822 to 1829 in all the liberated areas even in the periods when the Revolution had reached just before the crash, such as in 1826. Of course, all these did not overturn the structures and the attitudes of centuries of despotism. But even the last peasant voted, while at the same time fighting in the rear or in the front line killing his eternal fear in the face of the Ottomans, he worked and listened to the literati and the chiefs talk to him about his history and his worth and encourage him . Thus the villager evolved from a pure Christian to a Greek citizen.

Was '21, after all, class-based, as some historians have suggested?

There are no organized societies without some class structure, if, of course, we define social classes in some broader sense. So are the Greek ones. An old debate about the character of the Ottoman despotism under the question of whether it was feudal or not yielded almost nothing scientifically because the Balkan societies subject to the Ottomans were interpreted by historians in the light of northern European feudal systems of class formation.

The Ottoman imperial state constituted a variant of the Asian mode of production which we can accurately define as an Eastern-style agrarian despotism. From the end of the 14th, beginning of the 15th century, the Ottoman state evolved from an expansive predatory state into a permanent one and began to exercise power executively, i.e. transferring special (rather than general political) powers to a variety of small local and other vassal aristocracies of imperial scope. Among the latter I will mention the Orthodox priesthood organized in the Patriarchate of Constantinople as well as the priesthoods of the other churches as well as the Phanariot aristocracy. Of the local aristocracies, let me remind you of the provosts with the approximately two-year election as head of the province (kojambasi) and much less the charioteers because they had become autonomous to a certain extent. All these were dependent on the Ottoman state and their economic power did not derive from possession of a means of production, in this case land, but constituted income and accumulated as wealth for political use rather than capital. Instead, merchants, both land and sea (shipmen), constituted (along with intellectuals) the broad core of modern urban New Hellenism, and their power was expressed in commercial capital in all its forms:commodities, securities, ships, and cash. The Greek merchants, unlike for example the English merchants of the 17th and 18th centuries, did not rely on and never turned to land ownership. In any case, almost all of the land as a former Ottoman possession was nationalized by the first National Assembly and remained in the form of family lots in the hands of the cultivators against an additional small tax. Thus, during the Revolution, a social formation was formed, the broadest base of which consisted of producers who owned the means of production, were themselves a large part of the labor force and had political rights. Soon a République of small, mainly, owners was formed.

What historical lessons can we learn today from '21 and especially from the ferments that preceded the uprising?

Since February 1830, when the Greek Revolution ended largely victorious, the following pivotal question has been asked knowingly or unknowingly to every generation of Greek women and Greek citizens:

-If necessary, could we find relevant passwords?

-Would we raise our own flags?

-Would we take correspondingly high risk as our national ancestors back then?