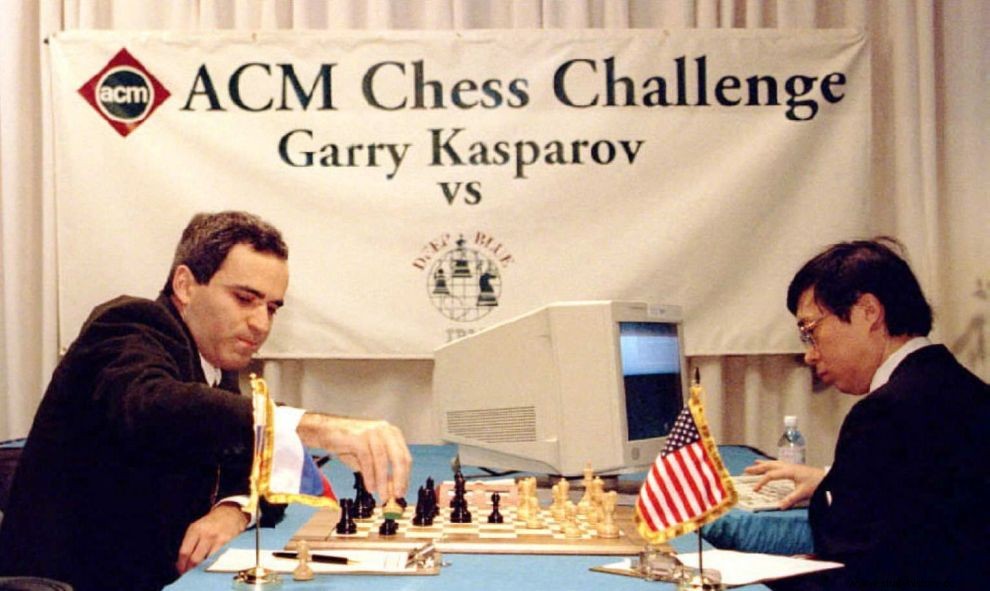

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. February 10, 1996 at 6:14 pm Garry Kasparov - considered by all experts of the sport to be the strongest player in the history of chess - rises from his seat, gives Feng Hsiung Hsu a cold look, shakes his hand congratulating him on his victory and walks away from the room. The moment is historic because for the first time in history, a reigning world champion is forced to defeat by a computer in a game with an official thinking time.

Deep Blue, the pride of IBM, has managed to trap the Azeri champion, disorient him and finally defeat him. Today, exactly 26 years later, the Magazine brings you the background of this duel, analyzing Kasparov's "opponent" and looking back at the main stages of chess matches between computer and man.

CHES &COMPUTER

Chess has always been considered an ideal field for the application of computers. Logically, chess is a simple game. On each move, the players choose from a series of continuations until there is a checkmate or a tie. In practice, of course, to implement this strategy, an astronomical number of moves must be considered, which is impossible. For this reason, both humans and computers rely on simplifications in order to make the most accurate chess model possible.

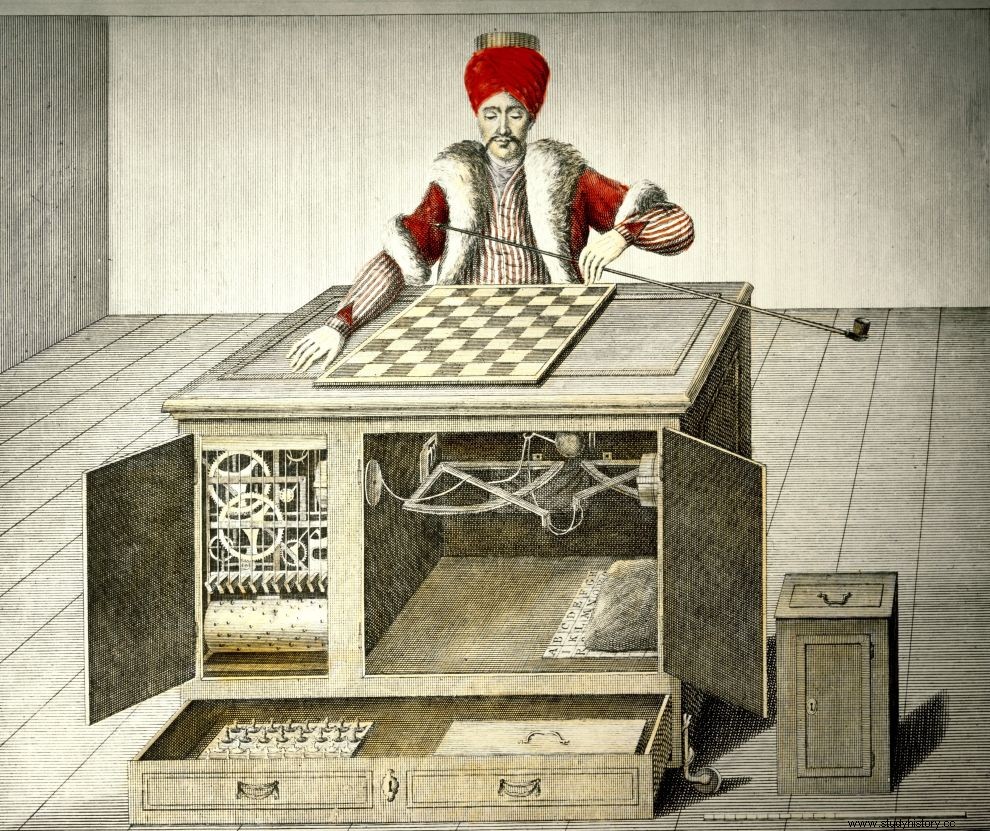

Humans rely on centuries of tradition and - most notably - 200 years of chess literature, while computers rely on the evolution of computational intelligence over the last 60 years. The idea of the chess machine dates back to 1760, when the Hungarian Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen toured Europe with his "Chess Automaton", a machine of his own invention, which was known as the "Turk" since the moves were performed by a puppet who wore a turban, through a complex mechanism.

The level of the machine was so good that in 1809 it beat Napoleon - quite a good player - in just 19 moves. Another known "victim" of the "Turk" was the also good chess player, Benjamin Franklin. The machine changed several hands until it was retired, ending up in the Chinese Museum in Baltimore, where it was burned after a major fire in 1854. However, the fraud was revealed in the following years:a powerful chess player was crammed inside the "Turk"!

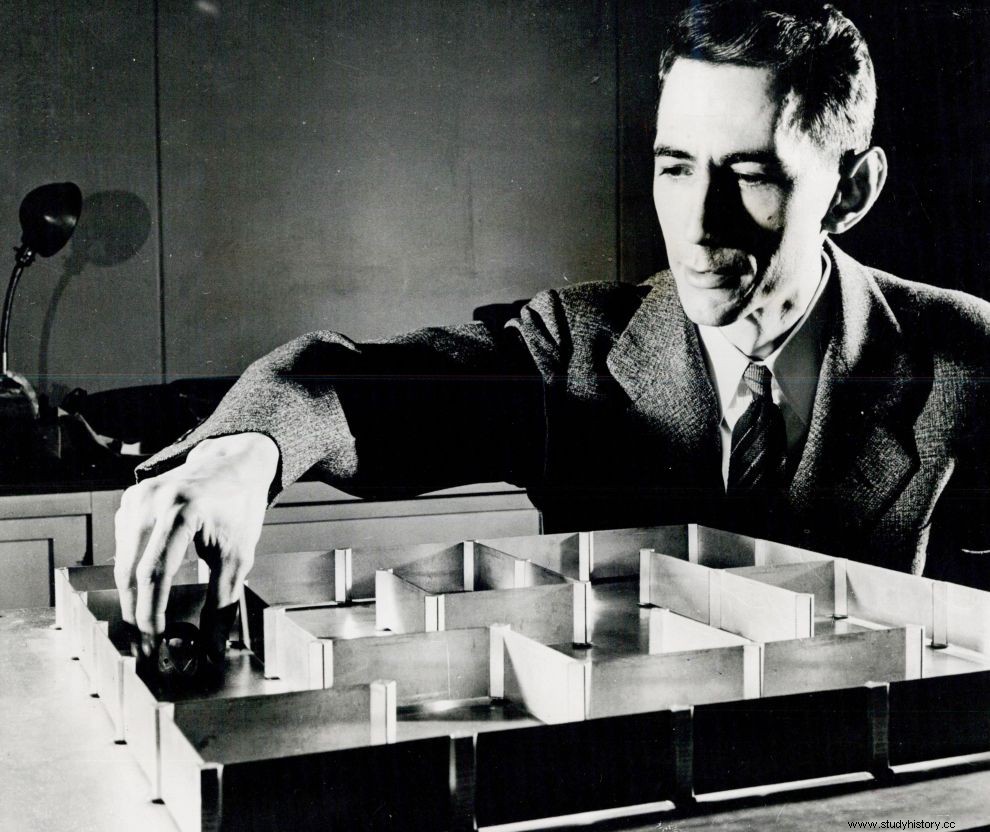

The English mathematician and cryptography researcher, Alan Turing (responsible for deciphering the German Enigma cryptographic device in World War II), first made the theoretical model of a program, but it was the American mathematician Claude Shannon who first established the minmax algorithm, the most important algorithm in the operation of a chess program.

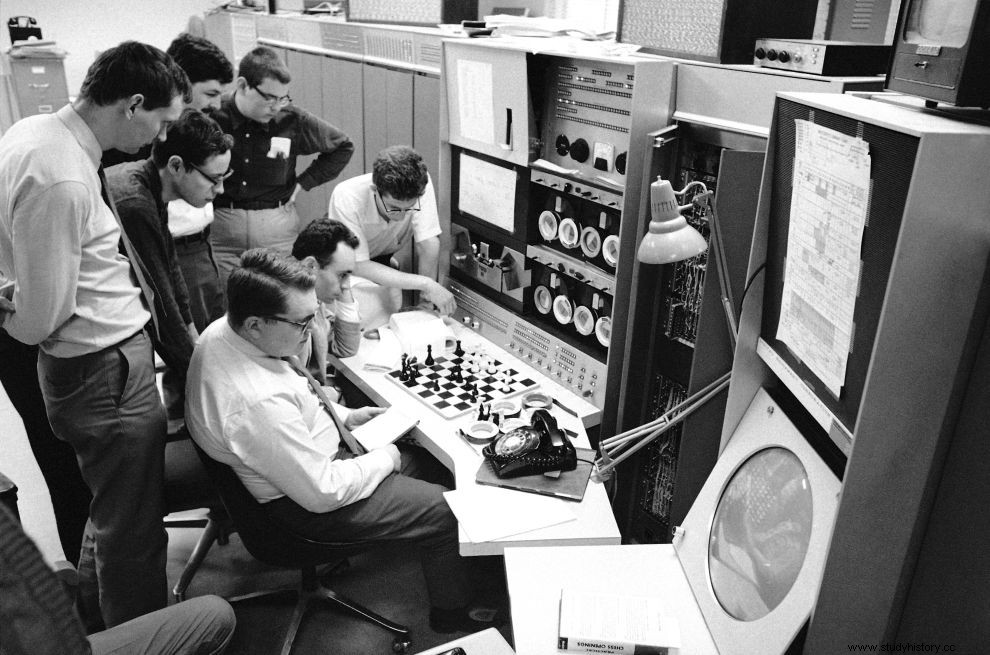

In 1958 for the first time a chess program won a man. But the opponent was the secretary of the company that developed the program, with a beginner's knowledge of the game. It was 1966, when for the first time a computer participated in a human tournament. MacHack VI created by MIT University, USA, took part in the Massachusetts Novice Tournament with one draw and four losses.

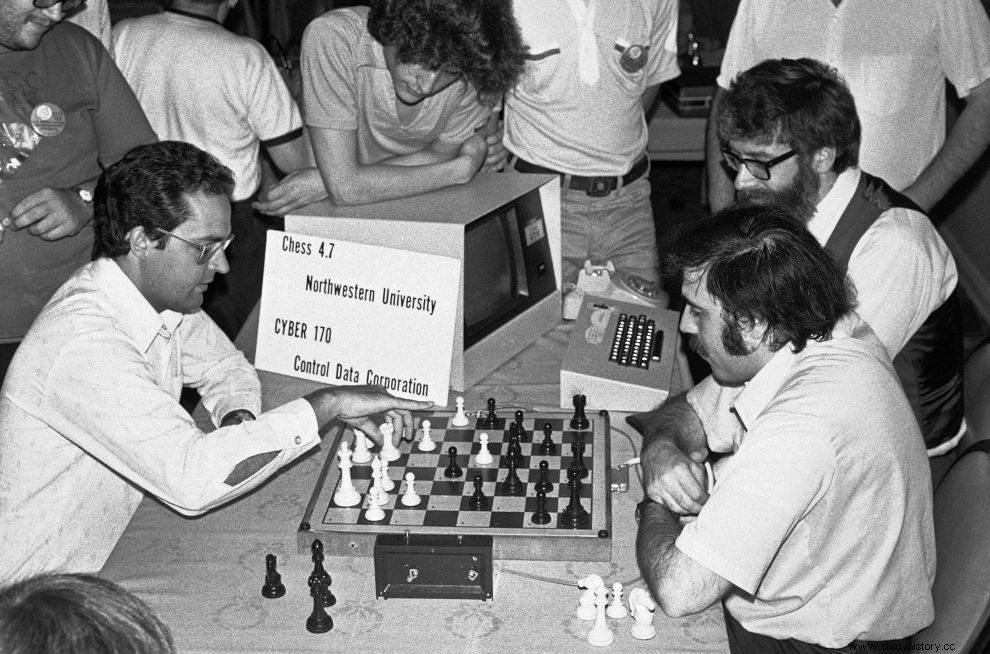

In 1968 the English international master David Levy made the most famous bet in the history of computer chess. He bet $3,000 that he wouldn't lose to a computer in the next ten years. The challenge was accepted by John McCarthy, a distinguished scholar of artificial intelligence. In 1978 Levy won the bet by defeating the Chess 4.7 program in Toronto 3.5-0.5. But it was the first time that a computer managed to get a draw from an international master.

THE FIRST VICTORY OF COMPUTERS

In 1981 the Cray Blitz computer won the Mississippi Championship with five wins, achieving a performance of 2258 Elo (a unit of measurement of a player's skill and level). In 1988 Deep Thought and Grandmaster Tony Miles shared first place at the US Open. Deep Thought performance reached 2485 Elo. By the early 1990s, chess program victories over well-known grandmasters were now commonplace. Hungarian Judith Polgar (the strongest chess player of all time), Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov were the most famous names on the list of computer "victims".

But the problems for the computer chess players started in the games with normal thinking time. In 1996, Deep Blue, despite losing to Kasparov 4-2 in the final, became the first computer to beat the world champion in a game with official thinking time. Until in 1997 came the big surprise. Upgraded Deep Blue beat Kasparov with a final score of 3.5-2.5. The world champion accused IBM of cheating, claiming that people were playing in addition to the computer and demanded rematch. IBM refused and took Deep Blue out of business.

HOW DOES THE COMPUTER PLAY CHESS?

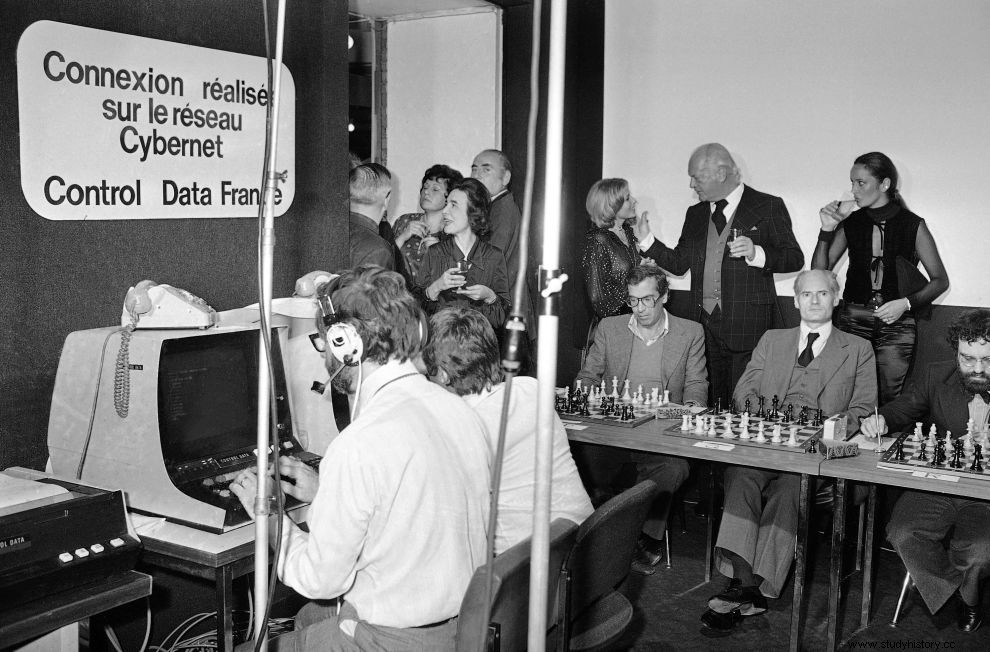

Today, tournaments involving chess programs are now an institution. Before we move on to the historic game Deep Blue - Kasparov, let's see how chess programs work. As we said in the introduction, trying for computers to estimate every possible continuation until the end of the game is practically impossible due to the sheer number of possible cases. There are two main strategies followed by chess software developers (both named after Claude Shannon). Let's simplify them for easier understanding.

- Shannon Type A: This formula takes into account all possible movements up to a certain depth. In order to be able to estimate the position that will result after some specific movements, the computer uses the so-called estimation function. Thus, with the help of some static and dynamic characteristics (such as material, growth, position of the king, etc.) the computer "scores" each position with a positive or negative number. In essence it is a "tree".

The root is the initial position and the branches and branches are the positions resulting after one, two and more moves. The problem with this function is that even the fastest processors are unable to go deeper than ten moves (such a ten-move-deep search requires studying a trillion combinations!). The solution could be to store the "tree", but that would require a huge memory space. So the computer is forced to calculate everything from scratch after every move.

- Shannon Type B: This approach limits the number of moves considered by the computer. About eight moves are thus selected for each position. However, the depth that the search will reach is not defined in advance. That is, it does not always reach the eighth movement, but it can be terminated much earlier. The study stops when a minimum depth of movements has been examined provided that the position estimate has stabilized. If the position is "unstable" - as it is during successive passages of pieces - then the study continues in greater depth.

In general, we can say that the first type is used in systems with high processing power (parallel systems) such as Deep Blue, while the second type is used in programs that run on single-processor systems such as PCs. To increase the search speed without needing more sophisticated hardware, special techniques are currently applied, the most important of which are the following:

- Opening Books: This is the computer's "book" of openings. The first 15-20 moves of the theory are stored in a database and recalled by the computer.

- Endgame Database: Similar to openings, a large collection of endings has been compiled for use by the computer. There are seats with up to seven pieces. The size of each database is of course different. From a few KB for the simple endings to GB for the more complex ones.

- Transposition Tables: Often the same position can result from different moves. To avoid unnecessary calculations, a number of moves are stored in memory. So when we reach a certain position from a different path, the computer retracts the position estimate.

Today, development is constant in chess programs. Every year a world computer championship is organized and every quarter the ranking of commercial chess programs is announced by the SSDF (Swedish Computer Chess Association, the organization responsible for evaluating and rating chess software). Of course there is no correspondence with human Elo, since the list is based only on matches between computers. Let's now take a closer look at Deep Blue's capabilities to understand what Garry Kasparov was up against.

DEEP BLUE CHESS COMPUTER

In 1985 Feng Hsiung Hsu, a naturalized American of Taiwanese origin and at the time a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania), created with two other fellow students a chess computer called "ChipTest", which it could estimate about 50,000 movements per second. Two years later, in 1987, the upgraded "ChipTest-M" had increased its performance tenfold, now estimating 500,000 movements per second.

Feng and his team continued to upgrade their creation, and when in 1988 they renamed it "Deep Thought" (adopting the name of a computer from the BBC science fiction radio series, "The Hitchhiker's guide to the Galaxy"), the estimate reached 720,000 moves. That same year (1988), "Deep Thought" became the first computer to beat a grandmaster in regular tournament play (Denmark Bent Larsen), but lost both of his 1989 games against Garry Kasparov with characteristic ease.

Despite his loss to the world champion, the performance of "Deep Thought" (who had meanwhile won the 1989 World Computer Chess Championship with an absolute 5-0) impressed the people at IBM, who suggested that Hsu work together . They began to explore parallel processing in order to solve complex computing problems, while a special team of scientists was created, who were exclusively engaged in the continuous upgrading of the program.

After "Deep Thought" was defeated by Kasparov, IBM held a contest to change the computer's name. The winner was Peter Fitzhugh Brown, a member of Hsu's team, who proposed "Deep Blue" (the "Deep" honoring "Deep Thought" and the "Blue" from IBM's nickname, "Big Blue") . Its analytical capability now exceeded 7 million movements per second!

TECHNICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF "DEEP BLUE"

Deep Blue was a parallel (32-node) RISC system running on an IBM-built RS/6000 SP computer weighing 1,400 kg! It was designed to play chess at the highest possible level, that of grandmasters. It used P2SC (Power Two Super Chip) processors. Each of the 32 nodes was equipped with 8 special microprocessor cards (256 in total). It took 5 years and millions of dollars from IBM to build it.

Deep Blue did not use artificial intelligence, there was no such formula. It relied solely on its computing power and estimative function. By the time he faced Kasparov (in 1996 and 1997), his analytical ability reached 200 million moves per second, and he could estimate within three minutes (the average time for each move in official tournaments) 200 billion moves, while grand meters can do the same for 500 moves.

Within his memory and for the opening of the lot alone, there were 4,000 seats and 700,000 grandmaster lots stored. Let's add here that Hsu's team had hired from the beginning of the 90s, the American grandmaster Joel Benjamin, as a consultant for the development of the "opening book" in Deep Blue, so that the computer would be ready to face the Kasparov. So having realized what exactly the Azeri champion was up against, let's move on to the historic first match of 1996.

PHILADELPHIA, USA, FEBRUARY 10, 1996

At 3:00 PM on February 10, 1996, Garry Kasparov entered the room where his six game match against Deep Blue would be played. Across from him sat the "father" of Deep Blue himself, Feng Hsiung Hsu, who had a terminal in front of him which was connected to the computer. The match level was 40 moves for each player in the first two hours of each game. Absolute silence was mandatory inside the main hall. The prize money for the winner was $400,000 and for the loser $100,000.

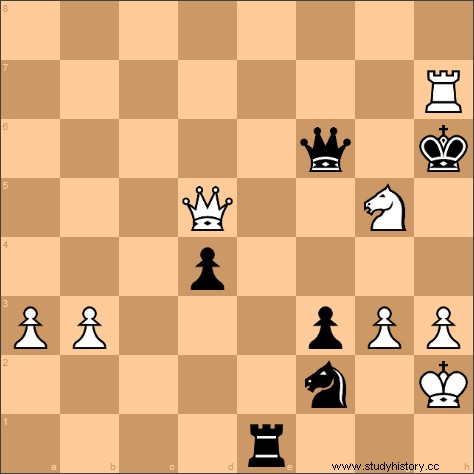

The two players began exchanging moves very quickly (chess fans can watch the game unfold here). Kasparov's tenth move "troubled" the computer and from that point the game got slower. Two moves later Kasparov left the room for five minutes, returned, stood over the table looking at the chessboard for another minute and left again. Seven minutes later he returned and moved his queen back one square.

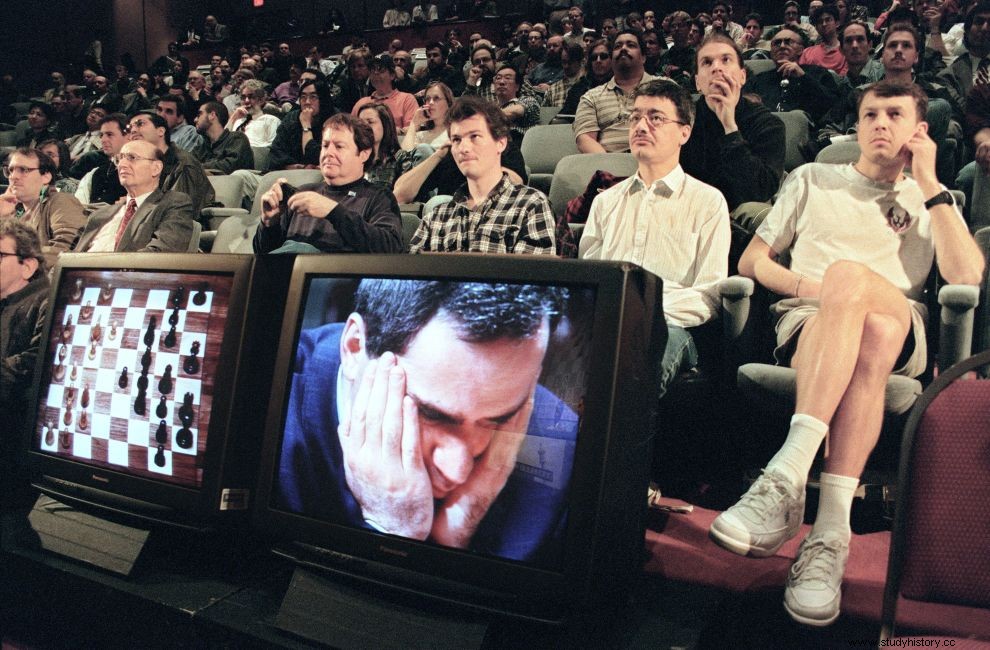

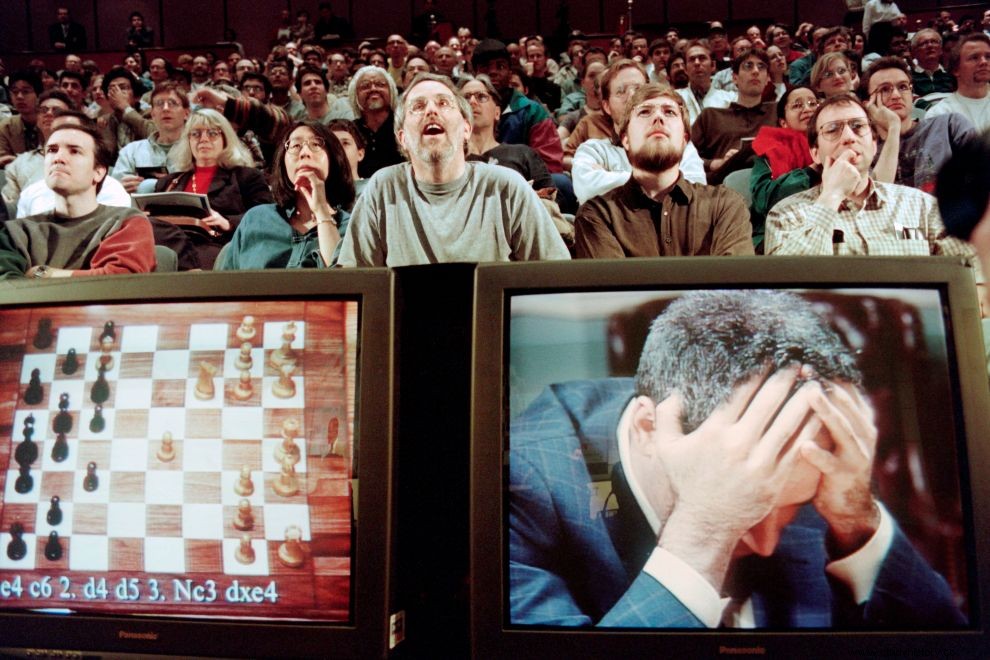

Deep Blue's next move, to threaten Kasparov's queen with a knight, caused the longest delay of the match. Azeroth analyzed for a full 27 minutes before moving the queen again. At the same time, in the adjacent room, 700 spectators watched the game, while various grandmasters analyzed the probabilities and the moves of the two players. The main hall, where the lot was held, was almost empty.

At 4.30 - an hour and a half after the start - the two opponents had played 24 moves each, but while Deep Blue still had 75 minutes to spare, Kasparov had just 41 minutes to his remaining 16 moves. The computer had already gained a great advantage. Behind the table were three cameramen, an official from the organizing committee, three members of Kasparov's team and a journalist.

All the others, unable to bear the mandatory silence and the tension that reigned in the room, had gone to the adjacent area, which was buzzing with anxiety and anticipation for the final result. Azeroth was completely engrossed making his familiar faces. But after a quick exchange of turrets, for the first time anxiety was painted on his face.

THE SQUADRON 28th MOVEMENT

A few moves later he left the room for another 12 minutes and returning (while his clock showed 25 minutes with 13 moves to go), he advanced an already exposed pawn. This move (the 28th) surprised all the experts, it was something unexpected. Kasparov later said that he had bluffed, which he regretted, since the computer cannot detect such tactics, so it does not fall into the trap. Deep Blue therefore unexpectedly found an opening, on which he could base his attack.

On his 33rd move (with 7:24 remaining) Kasparov crossed the entire chessboard with his only rook threatening Deep Blue's king. It was a desperate move to forestall the computer's attack. After protecting his king, Deep Blue threatened Kasparov three times in a row. At 6:14 p.m. Azeroth extended his hand and congratulated Hsu admitting his defeat.

HOW DEEP BLUE CAN BE DEFEATED

To beat a computer at chess, you have to be able to see deeper than it can. Computers "suffer" from the so-called "horizon syndrome". Due to the time constraint, they can advance their analysis only a few moves forward. Most of the millions of moves they can estimate are essentially useless in batches with formal (limited) think time. The computer cannot concentrate only on the "good" moves. He is obliged to examine them all. Όμως έχει συγκεκριμένο - περιορισμένο - ορίζοντα.

Ο ορίζοντας του Deep Blue ήταν τόσο ανεπτυγμένος, ώστε να μπορεί να αντιμετωπίζει με επιτυχία παίκτες του υψηλότερου επιπέδου. Δεν έκανε δηλαδή λάθος σε βραχυπρόθεσμες αναζητήσεις σωστών κινήσεων, αντίθετα ήξερε να εκμεταλλεύεται στο έπακρο τα λάθη του αντιπάλου. Άρα ο Κασπάροφ, για να καταφέρει να νικήσει τον Deep Blue, έπρεπε να ανακαλύψει πόσο μακριά μπορούσε να "δει" ο υπολογιστής και μετά να του στήσει μια παγίδα πίσω από αυτό το όριο, πίσω από τον ορίζοντά του. Ο Deep Blue θα συνειδητοποιούσε πως βρίσκεται σε κίνδυνο αρκετά πριν φτάσει σε αυτό το σημείο, όμως το πιθανότερο θα ήταν να βρίσκεται ήδη σε τόσο μειονεκτική θέση, που η ανακάλυψη της παγίδας θα τού ήταν πλέον άχρηστη.

Η ΑΝΤΙΔΡΑΣΗ ΤΟΥ ΚΑΣΠΑΡΟΦ

Τη νύχτα που ακολούθησε την ήττα του, ο Κασπάροφ ξαγρύπνησε πάνω από μια σκακιέρα, έχοντας δίπλα του το χαρτί της παρτίδας. Είχε ήδη μετανιώσει που δεν είχε πάρει στα σοβαρά τον αντίπαλό του. Αναλύοντας το παιχνίδι, συνειδητοποίησε πως ο Deep Blue δεν παρουσίαζε αδυναμία σε καμία από τις επιλογές του. Επικεντρώθηκε λοιπόν στο να βρει το βάθος του ορίζοντα του υπολογιστή. Όταν μετά από πολλές ώρες σκέψης και ανάλυσης των κινήσεων του αντιπάλου του ανακάλυψε επιτέλους τον "ορίζοντα" του Deep Blue, κατέστρωσε τη δική του επιθετική στρατηγική.

Έτσι, την επόμενη μέρα ο παγκόσμιος πρωταθλητής άρχισε τη δεύτερη παρτίδα εφαρμόζοντας μια στρατηγική τελείως άσχετη με αυτό που στην πραγματικότητα σχεδίαζε να κάνει. Καμουφλάροντας με επιτυχία την παγίδα του πίσω από τον ορίζοντα του Deep Blue, έδειξε ξαφνικά - στη μέση της παρτίδας - τις πραγματικές του προθέσεις, παρασύροντας σε λάθος εκτιμήσεις τον αιφνιδιασμένο υπολογιστή. Η συνέχεια δικαίωσε απόλυτα τον Κασπάροφ, ο οποίος ισοφάρισε με χαρακτηριστική ευκολία, προηγήθηκε το ίδιο άνετα 2-1 και τελικά αποδιοργάνωσε τελειωτικά το σκεπτικό του Deep Blue τελειώνοντας τον αγώνα με 4-2.

Όλο αυτό ίσως ακούγεται εύκολο. Στην πραγματικότητα όμως δεν ήταν καθόλου. Ο Κασπάροφ έστυψε κυριολεκτικά το μυαλό του προσπαθώντας να ανακαλύψει τον ορίζοντα του υπολογιστή. Και μετά ακολούθησε την ίδια διαδικασία ανάποδα μέχρι να βρει τα σημεία που θα έστηνε τις παγίδες του. Ο ίδιος χαρακτήρισε τον αγώνα ως έναν από τους δυσκολότερους της καριέρας του. Ενθουσιασμένος όμως από την πρόκληση, ζήτησε από την ΙΒΜ να διοργανώσει έναν αγώνα ρεβάνς για την επόμενη χρονιά, αίτημα που έγινε αμέσως αποδεκτό.

Φρόντισε βέβαια να αφήσει και τη σπόντα του ζητώντας από τους υπεύθυνους της ΙΒΜ να μην ξανασυμβεί στο μέλλον κάτι παρόμοιο με αυτό που έγινε πρώτο θέμα συζήτησης στη διάρκεια της 4ης παρτίδας. Τότε ο Deep Blue, αμέσως μετά την 22η κίνηση, κατέρρευσε πλήρως και σαν να επρόκειτο για έναν οιοδήποτε υπολογιστή της σειράς, ο υπεύθυνος τεχνικός αναγκάστηκε να τον βγάλει από την πρίζα και να τον ξανασυνδέσει αμέσως μετά, κάτω από το επιτιμητικό βλέμμα του συγχυσμένου Κασπάροφ.

Η ΡΕΒΑΝΣ, ΝΕΑ ΥΟΡΚΗ, ΜΑΪΟΣ 1997

Τον Μάιο του 1997, έναν χρόνο μετά την πρώτη συνάντηση, οι δυο αντίπαλοι ξαναβρέθηκαν αντιμέτωποι, αυτή τη φορά στον 35ο όροφο του Equitable Center στο Μανχάταν της Νέας Υόρκης. Ο Deep Blue παρουσιάστηκε "ανανεωμένος", με την έννοια ότι είχε διπλασιάσει την ταχύτητά του και είχε αναβαθμιστεί σε μεγάλο βαθμό, ειδικά στη μελέτη των ανοιγμάτων, εκεί όπου είχαν βάλει το χεράκι τους οι γκρανμαίτρ Μιγκέλ Ιγέσκας, Τζον Φεντόροβιτς και Νικ ντε Φίρμιαν.

Πριν την έναρξη του αγώνα, ο Κασπάροφ ζήτησε από την ΙΒΜ να του επιτρέψει να δει παρτίδες που είχε παίξει ο Deep Blue, ώστε να μελετήσει την καινούργια συμπεριφορά του υπολογιστή, αλλά εισέπραξε την κατηγορηματική άρνηση της εταιρίας. Δε θα επεκταθούμε περισσότερο σε αυτό το κείμενο στον αγώνα - ρεβάνς, όπου και επιβλήθηκε τελικά ο Deep Blue (χαϊδευτικά τον ονόμαζαν - λόγω της αναβάθμισής του - Deeper Blue) με τελικό σκορ 3.5-2.5.

Από μόνος του ο συγκεκριμένος αγώνας παρουσιάζει τεράστιο ενδιαφέρον, όχι μόνο γιατί πρόκειται για την πρώτη συνολική νίκη σε ολόκληρο αγώνα με επίσημο χρόνο σκέψης ενός υπολογιστή εναντίον ενός εν ενεργεία παγκόσμιου πρωταθλητή, αλλά και για το όλο παρασκήνιο στη διάρκειά του αλλά και μετά τη λήξη του. Πολλά ερωτήματα έμειναν - και συνεχίζουν να παραμένουν - αναπάντητα.

Ερωτήματα κρίσιμα για την κατανόηση της νίκης του Deep Blue ή αν το προτιμάτε, για την ήττα του Κασπάροφ. Όπως η ξακουστή "ανθρώπινη" αντίδραση του υπολογιστή σε μια κίνηση παγίδα του Κασπάροφ, κίνηση που μέχρι σήμερα όλοι οι ειδικοί έχουν χαρακτηρίσει σαν ύποπτη, σαν να προερχόταν από ανθρώπινο μυαλό δηλαδή και όχι από τον Deep Blue. Όπως η κάθετη άρνηση της ΙΒΜ να αποδεχτεί το αίτημα του Αζέρου για επανάληψη του παιχνιδιού.

Όπως το γιατί απέσυραν οι άνθρωποι της ΙΒΜ άρον άρον τον υπολογιστή από την αγωνιστική δράση - τη στιγμή μάλιστα του θριάμβου του και ενώ εκείνη την εποχή αποτελούσε την αιχμή του δόρατος στην εξάπλωση της φήμης της ΙΒΜ παγκοσμίως - αποσυναρμολογώντας τον και κλείνοντάς τον μέσα σε ένα μουσείο. Όπως το γιατί άλλαξε ο κανονισμός και δόθηκε η άδεια στους επιστήμονες της ΙΒΜ να επεμβαίνουν στον υπολογιστή ανάμεσα στις παρτίδες, κάτι το οποίο απαγορευόταν αυστηρά το 1996, στερώντας έτσι από τον Κασπάροφ μια από τις δυσκολότερες και εντυπωσιακότερες στρατηγικές, αυτήν της οριοθέτησης του ορίζοντα του υπολογιστή και του στησίματος παγίδων πίσω από αυτόν.

Το σίγουρο είναι ότι στον αγώνα του 1997, ο Deep Blue συνήθως πήγαινε την ανάλυσή του έξι με οκτώ κινήσεις μπροστά, φτάνοντας όμως σε κάποιες στιγμές μέχρι και τις είκοσι! Όπως επίσης, ότι εκτός από την "ακύρωση" του πλεονεκτήματος του Κασπάροφ σχετικά με τον ορίζοντα του υπολογιστή, ο Αζέρος βρέθηκε να μειονεκτεί απέναντι στον αναβαθμισμένο Deep Blue, όχι μόνο επειδή η IBM του απαγόρευσε να μελετήσει τις πρόσφατες παρτίδες του, αλλά και διότι η ομάδα του Χσου είχε αυτήν ακριβώς τη δυνατότητα, πρόσβαση δηλαδή σε όλες τις παρτίδες του Κασπάροφ.

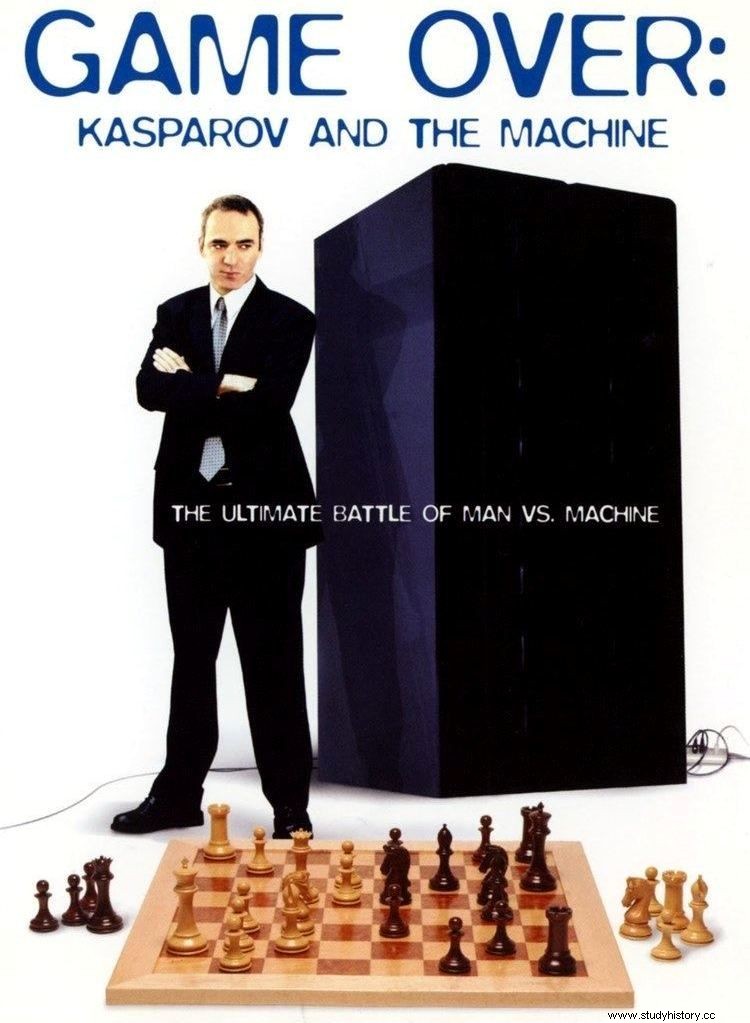

Ο Αζέρος, μετά τον αγώνα, ζήτησε εκτυπωμένα τα αρχεία καταγραφής του υπολογιστή, όμως η IBM αρνήθηκε να του τα δώσει (αν και αργότερα τα ανέβασε στο διαδίκτυο). Ο Κασπάροφ αποκάλεσε τον Deep Blue, "εξωγήινο αντίπαλο", όμως μετά από καιρό υποβάθμισε τις ικανότητές του, λέγοντας ότι "ήταν τόσο έξυπνος όσο και ένα ξυπνητήρι". Το 2003 γυρίστηκε το ντοκιμαντέρ "Game over:Kasparov and the Machine", στο οποίο βλέπουμε τη μάχη ανάμεσα στον άνθρωπο και τον υπολογιστή (αναλύονται όλες οι κατηγορίες του Κασπάροφ κατά της IBM).

Σήμερα, σώζονται δυο αποσυναρμολογημένοι Deep Blue. Ο ένας εξ αυτών εκτίθεται στο Εθνικό Μουσείο Αμερικανικής Ιστορίας (NMAH) στην Ουάσινγκτον, ενώ ο άλλος βρίσκεται από το 1997 στο Computer History Museum στην Καλιφόρνια. Πολλά βιβλία έχουν γραφτεί για αυτές τις δυο θρυλικές αναμετρήσεις ανάμεσα στον Deep Blue και τον Γκάρι Κασπάροφ, ανάμεσά τους και το "Behind Deep Blue:Building the computer that defeated the World Chess Champion", με συγγραφέα τον ίδιο τον Φενγκ Χσιούνγκ Χσου.

ΣΙΜΟΥΛΤΑΝΕ ΜΕ 25 DEEP BLUES!!!

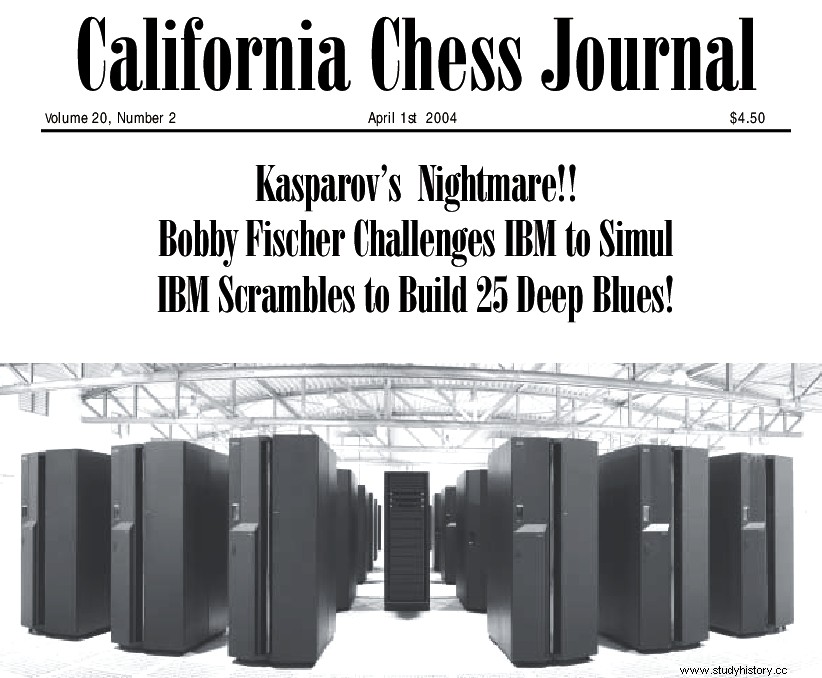

Πριν κλείσουμε αυτό το κείμενο, δε θα μπορούσαμε να παραλείψουμε την "ανάμιξη" του μεγάλου Μπόμπι Φίσερ στην κόντρα με τον Deep Blue. Ένα από τα σπουδαιότερα σκακιστικά περιοδικά των ΗΠΑ, το "California Chess Journal", στο τεύχος του Απριλίου του 2004, δημοσίευσε την εξής εντυπωσιακή είδηση:

"Ο Μπόμπι Φίσερ προκάλεσε την ΙΒΜ όχι απλά σε έναν αγώνα με τον Deep Blue, αλλά σε παρτίδα σιμουλτανέ (παρτίδα όπου ένας σκακιστής παίζει ταυτόχρονα με πολλούς αντιπάλους) με 25 (!) Deep Blues. Ο αγώνας θα πραγματοποιηθεί σε έναν μήνα από τώρα, αφού η ΙΒΜ αποδέχθηκε τους 5 όρους που είχε θέσει ο πρώην παγκόσμιος πρωταθλητής:

- Ο Φίσερ θα αντιμετωπίσει 25 Deep Blues στη σειρά.

- Οι υπολογιστές απαγορεύεται να είναι συνδεδεμένοι με το ίντερνετ, αλλά και κανένας γκρανμαίτρ δεν πρέπει να βρίσκεται σε απόσταση μικρότερη των 20 μέτρων από τους Deep Blues.

- Ο Φίσερ θα έχει τη δυνατότητα να μελετήσει έναν Deep Blue από κοντά, στην κατοικία του στις Φιλιππίνες.

- Ανεξάρτητα από το αν θα χάσει ή κερδίσει τον αγώνα, ο Φίσερ θα εισπράξει 1 εκατομμύριο δολάρια. Επίσης διατηρεί το δικαίωμα να ακυρώσει τον αγώνα ανά πάσα στιγμή.

- Καμία κάμερα δεν επιτρέπεται να βρίσκεται μέσα στην αίθουσα την ώρα της διεξαγωγής του παιχνιδιού.

Ήδη μεταφέρθηκε στη Μανίλα με απόλυτη μυστικότητα ένας Deep Blue, όπως είχε απαιτήσει άλλωστε ο Φίσερ ώστε να εξασκηθεί. Είκοσι άτομα χρειάστηκαν για τη μεταφορά και τοποθέτηση του υπολογιστή στο σπίτι του σκακιστή, ενώ οι άνθρωποι της ΙΒΜ τοποθέτησαν δυο ισχυρές μονάδες κλιματιστικών για να αντιμετωπιστεί η υπερβολική θερμότητα που παράγει ο υπολογιστής".

Φανταστείτε τον πανικό που δημιουργήθηκε στην παγκόσμια σκακιστική κοινότητα στο διάβασμα της απίστευτης είδησης. Τα τηλέφωνα έπεφταν βροχή στα γραφεία του περιοδικού, το οποίο όμως αρνιόταν να κάνει το παραμικρό σχόλιο. Οι προσπάθειες που έγιναν ώστε να εντοπιστεί ο Φίσερ στις Φιλιππίνες για να σχολιάσει την είδηση έπεσαν στο κενό, αφού εκείνη την εποχή ο σκακιστής κρυβόταν φοβούμενος τη σύλληψη από αμερικανούς πράκτορες, μια και είχε εκδοθεί σχετικό ένταλμα εναντίον του από τις αμερικανικές αρχές.

Η ίδια η ΙΒΜ βλέποντας στην όλη ιστορία μια ακόμα ευκαιρία δωρεάν προβολής της, επίσης αρνήθηκε να σχολιάσει το δημοσίευμα. Μέχρι που... Μέχρι που στο επόμενο τεύχος του περιοδικού, αυτό του Μαΐου δηλαδή, ο αρχισυντάκτης ενημέρωσε τους αναγνώστες πως η είδηση ήταν πρωταπριλιάτικο ψέμα!

* Βίντεο:Deep Blue vs Garry Kasparov, Game 1 (10/2/1996)

* Βίντεο:Τρέιλερ του ντοκιμαντέρ "Game over:Kasparov and the Machine" (2003)

Πηγές:cs.drexel.edu, academicchess.org, research.ibm.com, greekchess.com, chessgames.com, chesscorner.com, as.com, wiki