History, when it does not repeat itself, plays wonderful games in its relationship with the present. After all, if we are talking about projections that have a distance of 150 or 200 years (in history this specific period of time is not considered very long) it is clear that there are parallels and common points between the past and the present which leave scholars speechless.

The comparison of the coronavirus pandemic with the cholera epidemic in Greece in 1854 is one such field. Certainly one cannot speak of a repetition of the reality of 1854 in 2020 (today the pandemic is something that concerns literally the whole planet) but the similarities of the state response, the recording of the incidents by the press and the political intrigue connect in an amazing way the two seasons.

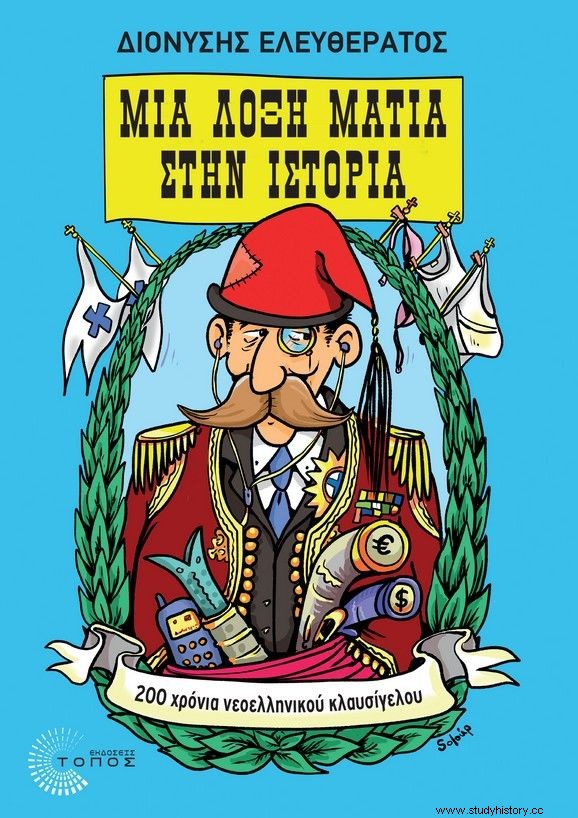

What you will read in the following lines is documented in the original and extremely interesting book by Dionysis Eleftheratos "An oblique look at History" (Topos Publications) from which we derive characteristic passages that prove that despite the time gap of 166 years the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 (in as far as the "Greek" part of it is concerned) "buttons" with the cholera epidemic in 1854.

A foreign epidemic that decimates Athens

In the middle of the 19th century, the capital of the embryonic, at that time, Greek state, Athens, had a population of approximately 30,000 inhabitants. Cholera killed 3,000 of them, i.e. 10% of its population, a huge number, even by the standards of the previous century. As stated in the book, "the miasma of cholera was almost certainly brought to Piraeus first by members of the French occupying military force.

Let the reader not be misled by the designation "occupational" for the allied force. That really was it. Both England and France had "captured" the otherwise sovereign Greek state in the wake of the then ongoing Crimean War. When this broke out, Greek guerilla bodies poured into the unredeemed areas (then Ottoman Empire territories) to occupy them, employing the military force of the Empire, which was then allied with the Anglo-French against the Russians in the Crimea. To stop the phenomenon, the allies effectively occupied Piraeus.

Cholera was therefore first observed in the ranks of the French military corps, that is, it was purely imported. At first the phenomenon was underestimated by the then government (Alexandros Mavrokordatos Prime Minister from May 1854). The informative document of the Minister of the Interior, Rigas Palamidis, which was sent to all prefects, is typical.

Therefore, Palamedes wrote:"With thanks, we announce to you, Mr. Prefect, that the epidemic cholera has begun to abate significantly. May we find ourselves in a position as we hope, shortly to announce to you the complete cessation of the suffering of this scourge." These were written around October 1854.

So, from the government's point of view, there was no particular problem. Cholera, which had first appeared in June, was adequately treated, completely controlled, and did not warrant any concern.

The pro-English press embraced this view and propagated it constantly. Through the pages of the newspaper "Athina", the world was informed that the epidemic was under the full control of the state authorities and that Piraeus was not facing the slightest problem.

In July, in fact, this particular newspaper accused the government that the measure of cutting off transport between Athens and Piraeus was completely unnecessary and that it was causing serious financial difficulties.

As Dionysis Eleftheratos notes, "Athina" called on the government to think maturely about the incalculable losses of so many destroyed commercial and industrial interests". In other words trade and economic life were more valuable than the protection of human life, even at that time.

Indeed, in Piraeus the disease was treated. But how; The "solution" was simple. The country's largest port was deserted. In Piraeus, according to the book, a few dozen impoverished families remained. Most moved to islands such as Syros, Spetses and nearby Aegina. In Aegina, in fact, permanent residents stoned the Piraeus "refugees" so that they would not approach the city.

Cholera "invades" Athens and destroys it

So it seems that the disease was treated in Piraeus. However, crucial details did not see the light of day. The then king Othona noted in his personal diary:"cholera was plaguing the French army in Piraeus and their leaders had the folly to hide it diligently by digging huge pits at night, where the dead were thrown, unseen".

Also, the doctors of Athens commented negatively on the fact that a "special zone" had not been created to prevent communication between Athens and Piraeus for obvious health reasons. And in addition, medical circles characterized two developments as extremely dangerous:the delay in the implementation of the Piraeus quarantine, but also the observed, frequent violations of it (if all this reminds you of something...).

The epidemic "broke out" in Athens in September 1854 with the first case being recorded by the authorities on Lysistratous Street.

Even then the phenomenon was underestimated. As we saw above, the Minister of the Interior was quick to reassure the prefects of the country by claiming that the epidemic was completely under control. Then the pro-Allied press took it upon themselves to "inform" that all was going well. On Wednesday, October 27, "Athina" wrote:"The daily cases are insignificant, so that no discussion should even be made about them. However, the residents must continue to strictly observe the dietary orders." In short, there is no particular problem (and this, probably, should remind you of something).

But the sequel dispelled the government myths propagated by the pro-alliance press (for a list...Petsa there is no information from the sources). Within 15-20 days the epidemic "hit" the capital mercilessly. "Athina" couldn't hide the truth any longer and on November 11th it wrote:"Yesterday and today the corrosive disease of cholera developed very rapidly and almost brought down the inhabitants." The newspaper even blamed this on the fact that items such as vegetables and wine were still being sold in the market.

ICUs, of course, at that time did not exist. The situation in the hospitals was desperate (which, we hope, will not remind you of something after a few days in today). The author-researcher of Athenian history Giannis Kairophylas writes about it:"In the military hospital, which was located in the area of today's Makrygiannis, people were dying. The beds were stuck next to each other in order to fit more inside the large rooms. Some (ss of the patients, usually soldiers) they had them lying down on the floor and there was a lot of rubbish around".

Panicked, the Athenians began to take the road to the suburbs of the city, mainly to the north (at that time even Patisia was a suburb, even a country house). 1/3 of its population stayed in Athens. The mayor Ioannis Koniaris was fired by the government, while many businesses were destroyed. Many of the Athenians "migrated" even to Piraeus from where the cholera had come to Athens. Unthinkable situations with the authorities watching embarrassed.

The pits opened for the cholera dead were, according to complaints, shallow and this constituted a great public health problem. And then the comparisons with abroad began. "Athina" was wondering why in Greece only 10% of the cases are cured while the corresponding percentage for Europe was even 48%? Apparently the answer had to do with the fact that the Greek state, heavily in debt from the first days of its existence, was not able to offer rudimentary effective health protection to its inhabitants (200 years the same story one would say).

Cholera finally subsided, as the book informs, in December 1854 after it had decimated Athens and caused enormous wounds to the social and economic "body" of the country. Entire families were uprooted, people died helplessly. But the occupying forces of the allies, who brought the epidemic to Piraeus and Athens, remained ...unmoved on Greek soil for another three years, only to withdraw in February 1857 (when the work in the Crimean War was successfully finished for them).

Read the News from Greece and the world, with the reliability and validity of News247.gr.