Legends of Water - and what lies beneath the murky surface - have existed as long as humans have had stories to tell. From monsters for mermaids, cultural belief in waterborne creatures has revealed itself in art, culture, history, and mythology - and has sometimes even worked its way into religion. This article will take a dive (no pun intended) through some of the most exciting myths surrounding sea creatures. And finally, we will conclude with their general cultural significance.

As above, then below

The written works of Pliny the Elder, a famous Roman writer, contributed to many medieval notions of marine life. For example, the belief that each land animal had its oceanic counterpart. Otherwise, the belief that the motion of the waves would cause animals to merge and form hybrids. He also described specific mythological creatures such as Blemmyes (headless men) and Cynocephalus (dog-headed people).

Illustrations of these creatures, among others, appeared in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), published by Albrecht Dürer. The Chronicle was one of the first printed books to combine written text with illustrations. It helped popularize both the existence and the images of mythical sea creatures.

Other written records from Western history describe the meaning and existence of sea creatures, especially details from travelers. This list includes Christopher Columbus, who reportedly came across three mermaids near Haiti. According to him, they were "not as beautiful as they are depicted." Historians now believe he came in contact with manatees, not mermaids.

Throughout the sixteenth century, the appearance of marine animals declined in written records. But their mystery, appeal, and frequent appearances in art and literature have not yet disappeared.

Sea Creatures in Scottish and English Lore

According to Scottish mythology, Ashrays are transparent aquatic animals. Also called water lovers, they can be both males and females, and can only be found at night, underwater - never above the surface. When caught and exposed to sunlight, they melt and leave a puddle in the wake.

Detailing Scottish mythological sea creatures would be incomplete without talking about the Loch Ness monster. Many people live in Loch Ness near Inverness, Scotland, and claim to be a plesiosaur (a carnivorous aquatic animal from the dinosaur era). Although people have claimed to have seen her, scientists have not yet found conclusive evidence of her existence.

Scottish sea mythology also discusses Selkies - sea lions that can shed their skin and take on human form. Selkies lived on the shores of the Orkney Islands and Shetland. They can be male or female. Historically, the Scots believed that when a female Selkie sheds her skin and is later taken by a human, she must marry them. However, if she found her Selkie skin again, she could go back to the sea and leave her partner alone.

On a darker note, British folk tales from Yorkshire mention the existence of Grindylows. These water demons had cruel, long fingers and wanted to drag children into the deep water. Parents wanted to tell their children stories about Grindylows to prevent them from getting into cold water, especially after dark.

Sea monsters in Greek mythology

If you are particularly interested in astrology and zodiac signs, then you have probably heard the word "Capricorn" before. But did you know that this sign shares its name with a Greek mythological sea monster? This half goat, half fish was apparently able to swim and lie on land as well as talk. Capricorns were often preferred by the Greek gods.

Greek mythologies, however, are also known for their terrible monsters - including Ceto, the daughter of Gaia (Earth) and Pontus (Sea). She is a personification of the sea's many dangers - namely its unforeseen damage. Her children were called Phorcydes - including Hesperides (nymphs), Graeae (water goddesses), gorgons (known for the hair of poisonous snakes). Eventually, Ceto became the general name for any sea monster.

Scylla and Charybdis are other examples of Greek sea monsters. Both represented the dangers of the rocky coast and a hot tub, respectively. Scylla is often depicted as a woman with a dragon-like tail, and dog heads sprout from her body, while Charybdis is illustrated as a deadly whirlpool.

At the back were Greek nereider friendly nymphs. Unlike their outspoken colleagues, they were always willing to help sailors through severe storms. They lived mainly in the Mediterranean. Examples of known Nereids include Amphitrite, Poseidon's wife and Thetis.

Finally, perhaps the most famous of them all was the Greek sirens. They wanted to lure sailors to their rocks by singing for them, and eventually made their ships sink. Sirens were often illustrated as women with the legs and wings of birds, playing a variety of musical instruments. Otherwise, artists would draw them as half-human, half-fishing creatures, much like more humans.

Sea Monsters in Chinese and Japanese Mythology

Chinese mythology, with its great focus on dragons, suggests the existence of Dragon Kings. These included four separate dragons, each of which ruled over the four seas to the north, east, south and west. They lived in underwater crystal palaces, guarded by shrimp and crabs, and could change shape into human form.

In Japanese mythology, Kappa are monkey-like underwater spirits with long noses and lime-green skin. It is believed that they lure children into the water and pull them down to enjoy the blood.

Umibōzu offers another example of a Japanese sea monster. Umibōzu, a giant, shadowy, humanoid monster, wanted to terrorize sailors during the voyage, bringing tumultuous waves, endless rain and versatile sea chaos.

Oceanic creatures from Norse and Scandinavian mythology

Fosse grim, according to Scandinavian mythology, was a water spirit. Like the sirens, he played enchanted songs on the violin and lured women and children to death. Some stories, however, portray him in a lighter way. In the lighter stories, he was a harmless entertainer of men, women and children with his music.

The Kraken name is recognized globally for its appearances in films such as Clash of the Titans and Pirates of the Caribbean. It is a Nordic sea monster with a legendary heritage, like its Scottish counterpart, the Loch Ness monster. Folklore describes the monster as a giant squid that lives deep in the ocean and appears every now and then to destroy ships. The name comes from Norwegian, which means "unhealthy" or "twisted animal".

Mesopotamian Sea Monsters

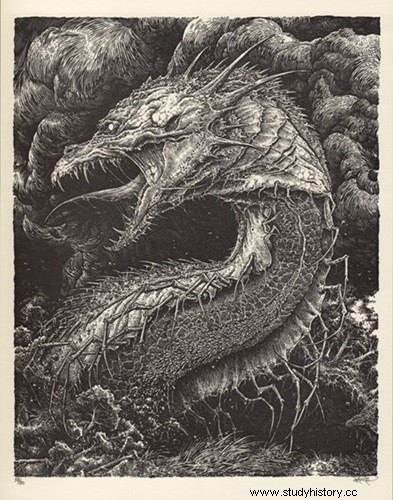

Among the most famous of all sea monsters is the biblical Leviathan, from ancient Canaan. He took the form of a giant sea serpent. He was originally described in the Old Testament as an aquatic reptile that God killed and offered as food to the Hebrews. Far from describing fearsome monsters, in modern Hebrew, the word "Leviathan" simply means "whale".

Leviathan lore evolved gradually, and his image slowly distorted more and more. Some religions portrayed him as a whale demon with several heads or a kind of water dragon. Some Christian interpretations say that he can only be a giant crocodile, while others portray him as a miserable demon with an indelible desire to consume all of God's creatures. He was thought to be the king of fish - and a remarkable liar.

Sea animals in Western European Lore

In European mythology, Melusine was a feminine freshwater spirit - not quite an ocean spirit, but still worth including in this list. She was a mermaid-like creature, sometimes with wings. Some believe that she was born of a fairy (Presse), and an ordinary mortal man.

Afterwards she went to the island of Avalon, where her parents then raised her. When her father betrayed her mother, she sought revenge on him. However, her mother heard about this and cursed her and forced her to look like a snake from the waist down. Because of this, her arms became weights, her hands fins, and she lived her life like half a reptile, half human.

More people are not limited to European mythology - every culture and / or religion has them in one form or another, but slightly changed. Like all the kids who grew up watching Disney's The Little Mermaid or displays as H 2 O:Just add water want to know, maybe humans are one of the most famous sea creatures - given their popularity in fiction, mythology and media.

More people usually have a human head and upper body, and a fish tail instead of legs. Males are known as mermaids and female traders as mermaids. In many stories they are beautiful and charming - sometimes to lure sailors and people to death. Some stories - including The Little Mermaid, as mentioned earlier - include mermaids that change shapes to look like humans, sometimes permanently, to live among humans.

Sea monsters in Eastern European and Slavic faith

Slavic mythology introduces us to Rusalka - female ghosts that haunt water bodies. Rusalka are the souls of young women who died in or near water bodies. Usually these were young women who had drowned to death, or otherwise been murdered. Their ghostly existence was often not violent, but they demanded that their death be avenged in order to move on to the next life.

Some suggest that Rusalka were women who died prematurely - due to suicide or murder. Therefore, in their ghost form, they continued to live out the specified time on earth as spirits. Others claim that Rusalka was the unclean dead - for example, unbaptized individuals.

Slavic mythology also suggests the existence of Vodyanoy (also spelled Vodianoi). These water spirits lived in underwater palaces, formed by sunken ships. They were old men, with long seaweed green beards. They were covered with hair, weights and slime - like the shipwrecks they often haunted. Like most sea monsters, Vodyanoy was feared because of their tendency to make people, especially swimmers, drown.

Unlike other monsters, however, they would not stop there. They would then take the drowned man down to underwater dwellings to serve as sea slaves - unless the man was a miller or fisherman, in which case they might have become friends with them or released them. Vodyanoy was usually married to Rusalka and, like Rusalka, represented the unclean (unbaptized or murdered) dead.

Polynesian and Native American mythology

The Tahoratakarar of Polynesian mythology is sometimes similar to the Greek mythological character Charon, who was in charge of the boat that ferries the dead to the entrance to the underworld.

In this myth, two evil spirits abducted a pregnant woman named Takua. These spirits stole her baby. After this the sea rose, and the two spirits dissolved in a cloud.

The boy, Tahoratakarar, was raised by the sea itself. When he was old enough, other sea spirits built him a boat connected to the underworld. The boat sailed at night and stopped for the people who died at sea. There the Tahoratakars would gather the soul of the individual and add them to the boat and transport them to the underworld. This boat became known as the Boat of Souls, or Boat of the Dead.

On the other hand, Native American (Lakota) mythology suggests the existence of Uncegila, a mighty water snake. She wanted to pollute rivers and flood land with salt water, damage crops and prevent agriculture and horticulture. This happened repeatedly until a pair of twins killed her by hitting the only fragile spot on her body. As a result, the sun scorched her body, as well as the soil of the surrounding land. This is what led to the development of the Dakota and Nebraska Badlands, a vast North American desert area.

Cultural significance of marine animals

The mythological and cultural folk tales surrounding the inhabitants of the sea tend to fall into two categories. First the helpful and kind - for example the Greek nereids, for example, or sometimes, the Nordic Fosse gloomy. Alternatively, the more common category of marine animals is monsters, which unjustly lure sailors and swimmers to death, or destroy their ships and cause enormous chaos.

Both types of sea creatures have influenced the artistic and cultural world. However, the latter legacy — from the Loch Ness monster, an impressive figure of timeless Paleolithic majesty, to Kraken — is far-reaching and all-encompassing.

Sea nymphs represent the knowledge of the sea - the surface, all that is within reach, and easy to see with our human eyes. The waves of the waves, grazed by the sand, a helpful hand that is easily accessible.

It is therefore no wonder that some of the most terrifying sea creatures exist exclusively in the depths of the ocean, lurking and threatening, ready to strike at any moment. They are the literalization of our fear of the unknown, of the enormous, enormous, incomprehensible death that the sea, in all its great emptiness, represents. These monsters - Grindylow, Charybdis and Leviathan - are externalizations of all of humanity's deepest fears. The invisible. The unknown. And death itself.