During an interview with Greek newspaper Ta Nea this year, Boris Johnson explicitly ruled out the return of the Elgin marbles to Athens. He insisted that Lord Elgin obtained the tiles from the Parthenon legally in the 1810s. Since then it is under the legal ownership of the British Museum in Bloomsbury, London. The Prime Minister's statement sparked further controversy over this disputed legacy. The Greek Minister of Culture, Lina Mendoni, rejected this view, stating that Johnson had not been briefed by competent scholars on new historical data. In an interview in 2020, Mendoni also branded Lord Elgin a "serial thief".

Elgin's dubious acquisition

The Elgin spheres are also known as the Parthenon spheres. Lord Elgin became the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in 1799. Greece was under Ottoman occupation. Elgin found that the Parthenon on the Acropolis was in a dangerous state after early Christian destruction and its conversion into a mosque by the Ottomans. An art lover suggesting that Britain could better preserve the sculptures, he negotiated what he claimed was permission from the Turks to remove some of the finest statues, metopes and friezes from the Parthenon. He then transported the marbles to London, and the British Museum purchased them in 1816. Although it appears that the Sultan gave two ratifications to Elgin, Greece argues that the Ottomans were foreign invaders who acted against the will of the people.

The debate

The war of words between Johnson and Mendoni revived the age-old debate over the Elgin marbles - who do they belong to, the British or the Greeks? Should Britain return the bullets?

This debate is historical, legal and moral. Nevertheless, I say that such a dispute has flooded the mainstream media. There has been extensive literature and opinion articles on the subject. The debate on Intelligence², involving Stephen Fry, is particularly excellent. Therefore, this article will not focus on this important but clichéd controversy. Instead, it will offer an analytical and historical account of the marble's significance to its owners and audiences from Imperial Athens, Georgian London, and then to modern London. It will explore the marble's colorful interaction with people.

Imperial Athens:The Parthenon and Its Marbles in Antiquity

After the victory over the Persian invaders, the statesman Pericles led the construction of the Parthenon. Work began in 447 BC. and was completed in 438 BC. by the architects Ictinus and Callicrates. Sculptor Phidias continued the fine decorations and carvings on the building until 432 BC.

What the Parthenon meant to its contemporary Athenians

Religion was at the center of Greek life. Before the Parthenon, the Athenians worshiped at an older temple known as the Older Parthenon. The Persian invasion of 480 BC then the destruction of such buildings. And after defeating the Persians at Eurymedon, it is only right to reconstruct the center of religious life.. The religiosity of the Parthenon was highlighted by the magnificent statue of Athena, patron of Athens, the center of the temple. It was Athena Parthenos:12 meters high, carved in wood and covered in ivory and gold.

Power and victory

As the ancient geographer Pausanias noted, Athena holds a statue of Nike four cubits high, and in the other hand a spear; at her feet lies a shield and near the spear is a serpent. The masses gathered outside the temple, offered prayers, poured out libations and offered sacrifices to the goddess of wisdom. But it is more than that. As Mary Beard argues inThe Parthenon Athena was not only the goddess of wisdom. Instead, she embodied a cunning intelligence that played an important role in carpentry, warfare and statecraft.

Indeed, this sense of militaristic prowess is evident in the Parthenon spheres. Some of the 92 metopes depict the Athenian victory over the Persians. Many young cavalrymen were prominent on these friezes. The statue of Nike, the goddess of victory held by Athena, also symbolizes triumph. From there it is clear that celebrating the victory over a formidable enemy like Persia is another goal of building the Parthenon.

Also, the temple served as a treasury for Athens, where officials managed the finances of the Delian League:an association with other Greek states against Persia, in which Athens was the dominant force. Overall, the Parthenon is a symbol of flourishing democratic Athens, where eligible male citizens could participate in public affairs. She gave a unique identity to the Athenians in the Greek world filled with oligarchies like Sparta and monarchies. Despite being a controversial form of government at the time, Athens rose above all challenges and produced the finest artists, architects, statesmen and military.

Georgian London:The British Pride and the Elgin Marbles

The meaning of legacy to the audience inevitably changes as the story progresses. To Londoners in the Georgian era, the Parthenon spheres had different connotations (here the word 'Georgian' refers to a period in British history, not the nation – Georgia). Lord Elgin's acquisition of the marbles was highly nationalistic. He moved heaven and earth to send them to London. In light of the European Art Race, at a time when countries like Bavaria and France were itching for antiquities, nationalism was a prominent motif.

Nationalism and the rise of classical art

Western civilizations greatly valued antiques and heritage in the 19th century. In Britain, newspapers usually present the news of antiquities acquisitions on global affairs pages, along with reports of battles. Britain, like its European counterparts, wanted to build an image of a cultured nation. British political elites at the time all had a classical education, and many were fond of Greek and Roman culture. In fact, as philosopher Denis Diderot argues, those who want to see nature must study antiquity. Therefore, the love of neoclassicism and Greek antiquities strengthened the drive to take possession of old works of art.

The central players in the race to acquire Greek and Roman classical art were France, Bavaria, Prussia, Russia and Great Britain. These powers invested considerable resources. For example, in 1842, to remove 80 tons of sculpture from Xanthos for installation in the British Museum, the British Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean ordered two naval ships and 160 enlisted men to recover the objects. The investment of labor and money reflects the importance of these antiquities' place in Britain's diplomatic mission.

On Elgin's return to London, the French cut him off and kept him in custody for three years. Elgin claimed that had he given a price for the bullets to be sold to Napoleon, freedom would have come sooner. In fact, as historian Merryman noted, Prince Ludwig of Bavaria also offered to buy the marbles, but Elgin stood his ground. At home, the sense of pride was evident. For example, the Elgin Report of the Parliamentary Select Committee of 1816 claims:

"No country can be better adapted than our own to give an honorable asylum to this [monument]".

Elgin Marbles and Race

The relative superiority of some races to others was an accepted belief in Georgian London. In fact, what we perceive as racist and derogatory today was a social norm for those living 200 years ago. This is also a dark side of heritage. Some columnists used the whiteness and masculine beauty of the Elgin marbles as a means of justifying British rule over the colonized world. For example, after the arrival of the bullets, the Investigator entitled an article – 'Negro Faculties', in which the author uses the marbles to contrast the cognitive abilities and cultural achievements of black people with white men:

"The exquisite, unsurpassed Greek form, set forth as the epitome of the physiognomy of the white race, is evident in the Elgin Marbles, which, when publicly studied by the Academy, will enable England, in art as in arms. , to give guidance to the world.”

(The Examiner (London):29 September 1811:'Negro Faculties')

Gender and masculinity

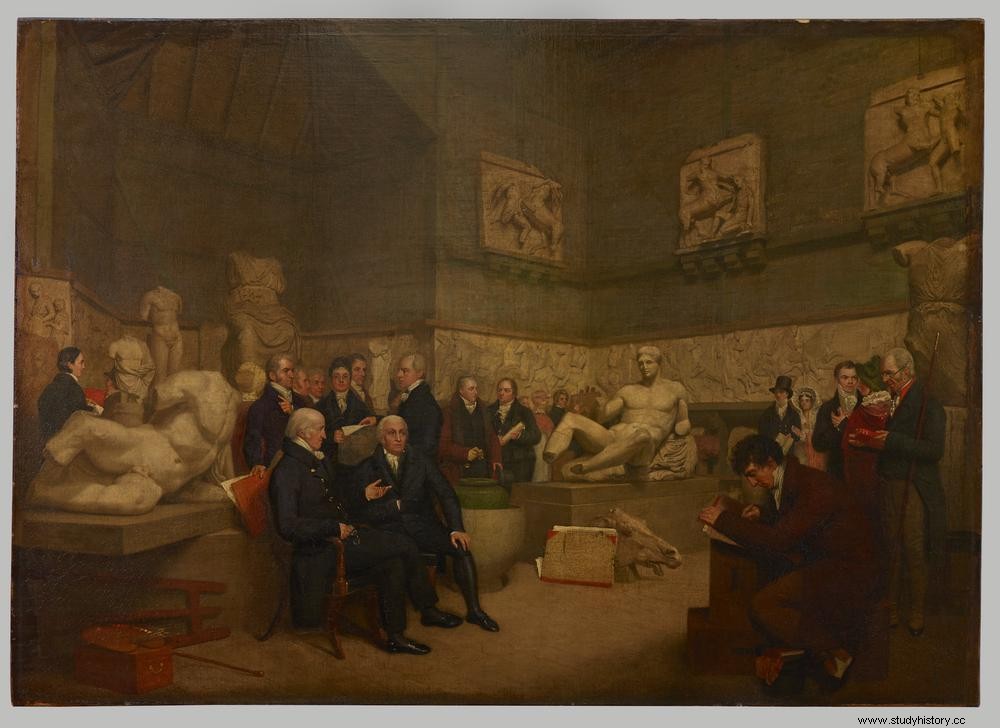

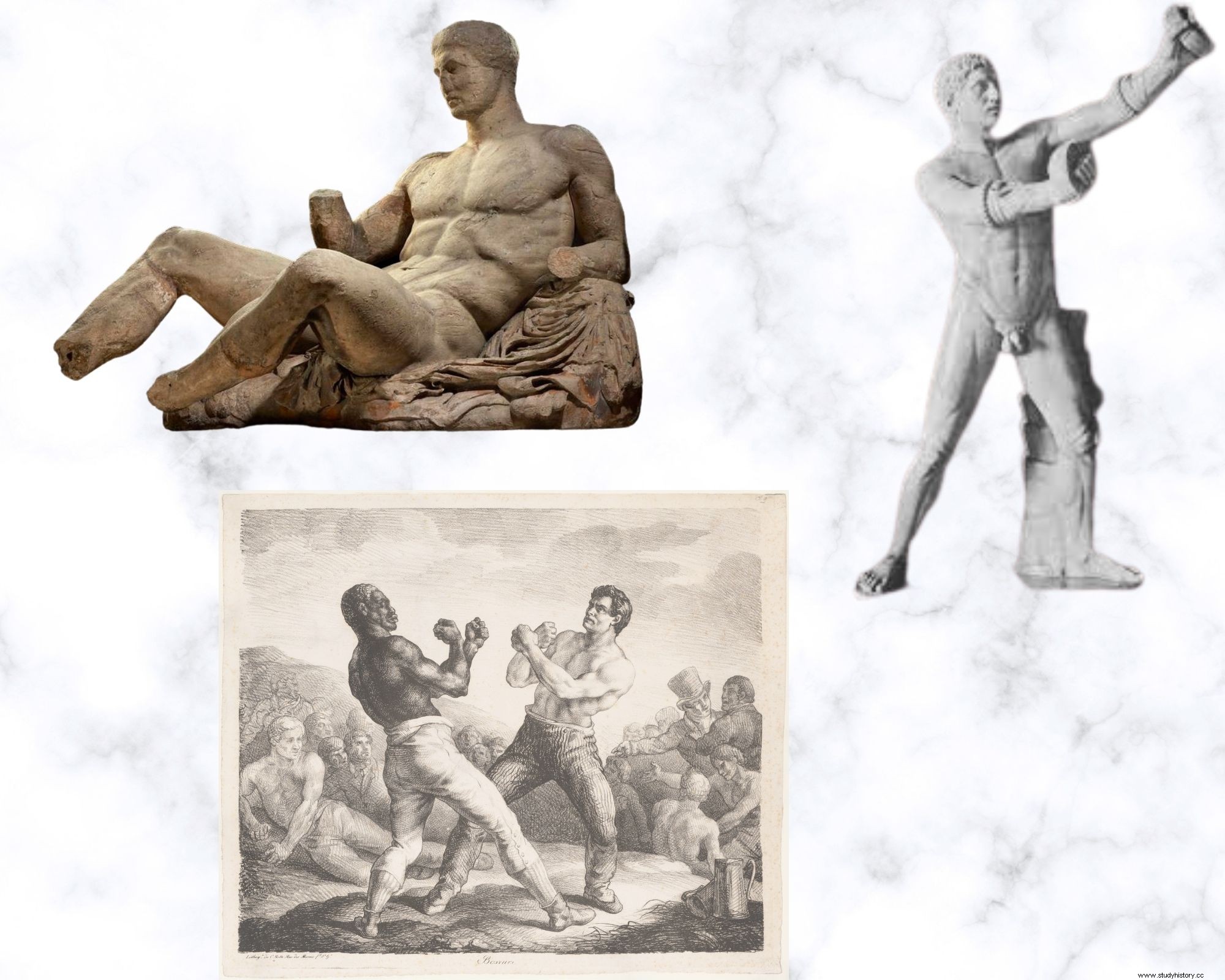

A curious reaction to the Parthenon Marbles occurred after their first arrival in London. Elgin balls are also heirlooms that reflect community values. In 1808 they entered the world of sport and shed light on the social codes of masculinity. To drum up the initial publicity for the bullets, Elgin invited boxing icons and arranged lavish prizefights next to the bullets, where the elites cheered and bet on the fights. The physical beauty of the statues acts as a backdrop to the physique of the boxers.

Elgin invited many big shots in those days. For example, Jem Belcher, English champion from 1800 to 1805. Masses across different classes supported prizefighting, as it was a traditional sport reflecting the courage and manliness of Englishmen. Boxing champions were national heroes. Historian Leoussi suggests, through the juxtaposition of the boxers and spheres, Elgin persuaded his audience of sculpture's natural place in Britain:

"If the naked celebrities looked like mounted Greek warriors in the frieze, then Britons could assure themselves that they were the embodied heritage of ancient Athens."

Moreover, what such a juxtaposition reveals are the codes of masculinity that the boxers and clinchers embody. Compare a fighter plane with Dionysus. They share perfection in robustness, fertility and heroism. Dionysus is the god of fertility and saved the princess of Crete, Ariadne. Georgian elites were undoubtedly aware of these qualities due to their classical education. When the stage actress Sarah Siddons visited Lord Elgin's showcase in Park Lane to see the Parthenon sculptures, awestruck, she reportedly fainted at first sight of the marbles. Georgian's emotional engagement with the spheres shows the presence of Elgin spheres that are romanticized and embody masculine virtues. They represent an ideal that the masses admire.

Modern London

Currently located at the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum, the marbles are visible to 6 million visitors each year. The bright and spacious Duveen Gallery is located towards the end of the Ancient Greece exhibitions. It was purposely constructed in 1928 to display the sculptures. The purposeful architecture of this space and the use of large translucent panels allow visitors to view the sculptures in natural light. And this reflects the history of the sculptures as they were once presented in the Parthenon, intended to be seen under the natural Greek sunlight.

Historical education and the British Museum

While many of the visitors are tourists who may appreciate the sublime beauty of the spheres but do not delve deeply into the history, there are many students of art, anthropology, history or classics who will undertake in-depth research into this heritage. For them, the British Museum is an oak of knowledge that arouses interest. History and classics students could delve into comparative history and contrast and evaluate the acquisition context and materials of the marbles with other sculptures from the Greek world. Budding artists could note the statues' shape and recreate them with originality and modern styles as training.

Heritage as inspiration for artists and architects

In an interview with The Guardian, former arts minister, Alan Howarth, states that the beauty of marbles rises above the banal and is a heightened experience in which the whole personality is engaged. After seeing the bullets, Howarth asks:'why should we tolerate mediocrity and ugliness in our buildings'?

Whether the flowery words are the honey of a seasoned political rhetorician or the genuine reflections of an art lover, I do not know. Nevertheless, Howarth's idea of using marbles as an artistic experience has been used frequently in the last decade. Many art projects have recreated the Parthenon Marbles.

Architect Niall McLaughlin reproduced the spheres in concrete and adorned them on block 15 of the London Olympic Village 2012. In an interview with The Architectural review , McLaughlin himself expresses wonder at the changed lives of the Marbles:

"Damaged by volcanic ash, burned in a fire, destroyed by Christians, robbed of their metal by Turks, blasted by Venetians in a bombardment ... I have a feeling that Elgin Marbles are fragmented and lost. They were made under the eaves of a particular building at a particular time by particular people, with a particular set of meanings at that time."

Marbles and the London Olympics

McLaughlin's deliberate juxtaposition of the Olympic Games with the clinches has many meanings to which one can attach. The obvious one is the transfer of the Olympic torch from Greece to Great Britain. But it is more than that. The Elgin Balls, like the Olympics, are a universal human heritage that endured the wear and tear of past conflicts, and were constantly politicized, but they retained their beauty, just as the Olympic Games maintained their faith through times of racism and war. This is something the masses should recognize and cherish.

Final Thoughts

For us, the Elgin marbles have educational value. Either to inspire the students' nascent interests in liberal arts, bring out artistic inspirations or promote cultural understanding such as the Olympics. For elite Britons in the Georgian era, the balls symbolized masculinity, justified colonialism and represented their identity as a cultured nation. For Athens, the orbs reflect the triumph of their people, government and artists over their Greek counterparts, as well as a sacred dedication to the goddess they fear and love. I don't think the current overemphasis on 'who the latches belong to' is correct. Because not only does the debate get nowhere, it also diverts the scrutiny of heritage from an anthropological perspective. The many lives of the Elgin marbles and other legacies deserve to be told, because they are fascinating and colorful, they open a new door to historical analysis.