A look at Argentina's Patagonian Welsh community

Buenos Aires, Argentina's vast Atlantic metropolis, captivates visitors with its mix of French, Italian and Spanish architecture and cuisine. Patagonia, on the other hand, hosts a more unusual culture in the vast and once barren Chubut Valley.

The Welsh cities of Puerto Madryn, Trelew, Rawson, Gaiman, Dolavon, Esquel and Trevelin tell the story of determined immigrants who, fleeing oppression in their homeland, successfully preserve their language and culture in the most unlikely places.

The story of Welsh emigration

By the nineteenth century, the Welsh were no strangers to economic hardship and oppression. The development of the Industrial Revolution began to shrink Wales' rural communities, and hastened to meet a growing demand for coal, slate, iron and steel. And the notion that England gradually absorbed the Welsh language and culture, especially its non-conformist Christian population who opposed the Church of England, had existed for centuries.

In the 16th century, King Hentry VIII enforced the use of English in Welsh courts and banned the allocation of public office to Welsh speakers. By the 19th century, the country had regarded English as the language of social and economic progress and Welsh as the language of the backward. A parliamentary report from 1847 on Welsh education entitled The Betrayal of the Blue Books mocked the Welsh language and culture and imposed on school children who spoke Welsh hanging Welsh notes.

A written account expresses the urge to flee from such oppression:

"I remember those times in Wales, when day after day we felt the pressure of foreign cultures penetrating our own homes. Our Welsh souls needed independence; to gather and sing at our chapels ... That was when the idea of emigrating began to grow strong. The plan was to leave Wales in an organized group, and find a land of virgin lands, a land that would enable the arrival of a significant number of people and where we could develop, or in other words, establish ourselves as a Welsh colony, as in New Wales. "

Finding a place where the Welsh could flourish and preserve their language and culture appealed to many. Pressure to adopt the English language and American industrial culture spoiled the first attempt to establish colonies in the United States, perhaps most notably in Utica, NY and Scranton, Pa. The Welsh realized that they would only really succeed in maintaining their lifestyle by establishing themselves in a place where English had not yet reached.

Looking for a new home

In 1861, emigration enthusiasts met in the house of nationalist and Congregationalist Michael D. Jones in the town of Bala in northern Wales. Jones, who was to establish several Welsh emigration communities, originally moved to Ohio and understood the struggle his people faced both at home and abroad.

The group discussed the possibility of "promised land" that exists for those outside the United States. The nineteenth century saw much Welsh immigration to other English-speaking nations such as Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. In particular, Vancouver Island, BC, garnered much appeal. But no matter where the Welsh looked, they did not weigh higher quality of life and better work up the fear of losing their heritage and identity.

Jones corresponded with the Argentine government to settle in the modern port city of Bahía Blanca, despite the fact that the native Tehuelche people already occupied the country. In addition, Lewis Jones, a publisher from Caernarfon, visited Patagonia in 1862 with Sir Love Jones-Parry, a Welsh politician who owned the Madryn estate.

Argentina eventually agreed that the Welsh should settle in the Chubut Valley and freely retain the language, culture and traditions there. Such a settlement also benefited the government because it gave Argentina the right to a large piece of land it had disputed with Chile. Argentina's constitution of 1853 also encouraged European settlement around Patagonia to improve industries and bring agriculture, arts and sciences to the region.

"Colonies"

One of Michael D. Jones' committees met immediately in Liverpool and published Llawlyfr y Wladfa to serve as the handbook of the Patagonian colony. Lawyers published the book and the scheme widely around both Wales and its American settlements, promoting the idea of Argentina's first Welsh colony ( Y Wladfa ).

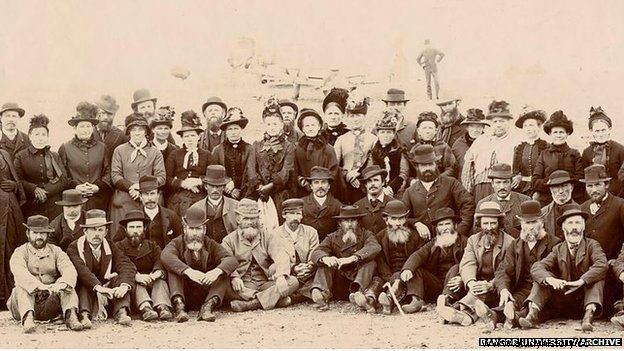

The first group of settlers consisted of over 150 people from all regions of Wales, especially from the Rhondda Valley communities in the south such as Aberdare, Mountain Ash and Abercwmboi. Together in solidarity, they set sail from Liverpool at the end of May 1865 aboard a tea mower called Mimosa. As passengers, they paid 12 pounds sterling per adult and six per child, although most came as families and lacked wealth.

Much thanks to the good weather, the Mimosa arrived in present-day Puerto Madryn in Golfo Nuevo on July 28, about eight weeks after departure. As agreed, two delegates waited for them in cabins on the beach and provided them with pets.

An unpleasant surprise

The settlers expected green and fertile lowlands compared to Wales, and rose up on the barren and windswept Pampas and, after a long drought, found little food and water. The absence of forests to provide building materials meant that settlers had to dig some of their first homes into the cliffs by the bay. The area is today known as Punta Cuevas and contains around nine man-made caves and shelters.

Tehuelche originally sent a letter to the Welsh in December 1865, introducing them to the surrounding indigenous groups, including the Mapuches and Pampas, and asking for trade activity. They also taught the settlers how to survive in the adverse prairie conditions, and showed them how to hunt and exchange guanaco meat for bread. In any case, the severe shortage of food continued to set the odds against the Welsh.

In return, they treated Tehuelche with considerable justice and respect, something the Argentine government did not have during its Desert Campaign against Indigenous Peoples living on top of Patagonia. A settler's account remembers initial interactions with Tehuelche:

"We did not trust the Aborigines at first because we were afraid of them. But soon we discovered that we could all live in harmony, and began to exchange bread and butter for meat and goods used to make clothes. "

After orienting itself, the Welsh headed 65 kilometers south to establish their first permanent settlement, Rawson, along the Chubut River at the end of the year. The Welsh name of the river, Afon Camwy , described it as «twisting». And the river's floods, along with poor harvests, land ownership conflicts and limited sea access, would create some challenging first years for settlers.

A glimmer of hope

A settler named Rachel Jenkins noticed how the blasting of the banks of the Chubut River, while destroying attempts to develop the colony, also brought life to the surrounding arid land and formed drinking lagoons. Her observation led to the development of a life-saving irrigation system that brought an abundance of wheat crops. This became Argentina's first artificial irrigation system and also caused a railway to be built between Puerto Madryn and the later settlement of Trelew, named after Lewis Jones.

Subsequent settlers from Wales and Pennsylvania brought the population over 270 by 1874. They helped dig new irrigation canals through the Chubut Valley, and a patchwork of farms soon began to appear on both sides of the river. The Argentine government officially gave the settlers the right to land in 1875, which attracted another 500 people from Wales, especially from the southern coal fields which were then undergoing depression.

Similar large-scale migrations occurred between 1880 and 1887 and between 1904 and 1912. Some settlers also returned to Wales to persuade more people to join their settlements, as others began to venture elsewhere in Patagonia and beyond. A report describes the coming and going of settlers:

"Some of our men traveled back to Wales to convince and attract more people. After a few months of preaching about Patagonia, two groups were formed:one in Wales and the other in the United States, where there were also Welsh. They headed for Buenos Aires, where they were made available by a ship that took them to Chubut. It was 1874, a very good year for the harvest, a fact that helped maintain the original enthusiasm. "

In any case, the settlers maintained their schools, chapels and local authorities as fully Welsh-speaking institutions. Over two dozen Welsh Protestant chapels grew up in Trelew alone, including Capilla Moriah and Capilla Tabernacl. In addition to serving as religious centers, these easily identifiable buildings also served as educational and judicial institutions where the whole community discussed projects and actions.

A saying goes that while a newly arrived Briton is building a shop and a newly arrived American is building a school, a newly arrived Welshman is building a chapel. Nevertheless, the Chubut Valley also became home to the very first Welsh-language primary and secondary schools. The settlers even managed to keep the government, businesses and social life and letters, diaries and records mainly in Welsh.

The region was to become one of Argentina's most productive and fertile agricultural areas, and the Welsh expanded their presence and influence in the early twentieth century as far as Cwm Hyfryd (Pleasant Valley), their settlement at the foot of the Andes. The settlers certified in 1902 the protection and sovereignty the Argentine government had given them, as the country continued to engage in land conflicts with Chile. The Welsh went so far as to call themselves loyal to the country, with some proudly regarding themselves as native Argentines.

So close, yet so far

Unfortunately, the success reached their many non-Welsh ears. In 1915, half of the population of the Chubut Valley consisted of 20,000 XNUMX people immigrants from other parts of the world. Domestic migration, immigration from Chile, and breaks in shipping from Wales during World War I led to an influx of Spanish-speaking settlers breaking ties with their Welsh homeland.

The Argentine government also advocated the introduction of direct rule over the colony and an end to the institutional use of Welsh everywhere except in chapels. While the settlers came to preserve their own culture, Argentina aimed to build its own identity strictly through the Spanish language, which meant no bilingualism. By the 1940s, marrying outside the Welsh-speaking community had become the norm for settlers.

Patagonian Welsh

Despite similar repression from another dominant force, the settlers continued to preserve their language and shaped it to become particularly unique in itself. Welsh in Patagonia combined dialects from North and South Wales and also implemented elements from local Argentine Spanish. Many visitors left Wales in 1965 to celebrate 100 years of successful Welsh settlement in Patagonia. Upon arrival, they learned to their surprise that the dialect of the inhabitants had remained untouched by English, albeit also significantly influenced by Spanish.

Exposure to one of Latin America's lingua franca made the Welsh settlers' pronunciation of the plosive consonants b, c, d, g, p and t less profound and softened their pronunciation of "ch." Changes in traditional expressions back in Wales also developed over time. While some in Wales welcome you in with "dewch i mewn" ("come in"), for example, one often hears "pasiwch i mewn" ("fit in") in Patagonia's Welsh community. In addition, talking on the phone, "siarad ar y ffôn" has developed in the Chubut Valley to become "siarad dros y ffôn" derived from “Hablar por telefono.”

Lost in translation

Lewis Jones' Welsh-language newspaper in Patagonia, Y Drafod , contained ads from local business owners who often did not speak the language. Regardless, their efforts to market their products and services led them to create new concepts that fit the developing society.

Arianfa , which means "bank", comes from Welsh for "money" or "silver". Imdrochfa , which refers to a spa or similar bathing resort, is derived from the Spanish term Spa . Imagination Watch , from the Spanish office , means a "practice" or "office", as in ymgynghorfa ddeintyddol (a dental practice). And oriadurfa a thlysfa , Welsh for relojería y joyería , describes a store that sells watches and jewelry.

Today, most of Patagonia's Welsh people born before 1950 speak the language as their first language, while most people born after 1970 who speak it have learned it from a Welsh tutor and know it as a second or third language. Descendants of early Welsh settlers now make up about 20,000 150,000 of the Chubut Valley population of around 5,000 25 people, and around XNUMX XNUMX of them (XNUMX percent) can speak Welsh.

Back in Wales, only about 20 per cent of the population actually knows the language, and the first thought of a native Argentine speaking it fluently, many wonder. In recent years, however, Bangor University and the National Center for Learning Welsh have collaborated to design a Patagonian Welsh language course.

Argentina's Welsh heritage today

Despite significant Spanish-language influence, the culture of the original inhabitants of Welsh Patagonia remains intact. The presence of Welsh tea houses and the celebration of eisteddfodau Language and cultural festivals, among other factors, have helped maintain their heritage. These festivities are held around the end of April, and include competitions, city dinners and Cymanfa Gunu holy hymn festival.

The communities of Gaiman, Trelew and Esquel celebrate every July 28 with Welsh tea, song and poetry to mark the day of the arrival of the first settlers to Patagonia. The first landing over 150 years ago, known as Gŵyl y Gland , recreated this day in the port of Puerto Madryn. Another Eisteddfod takes place in Gaiman during September, and the Welsh- and Spanish-speaking Chubut Eisteddfod , Patagonia's largest Welsh cultural festival, takes place in late October and attracts visitors and competitors from abroad.

With a population of 100,000 80 people, Puerto Madryn now thrives on its large aluminum plant and tourism oriented around whale watching. Trelew, XNUMX kilometers south, serves as a hub for the wool trade and houses schools that provide both Welsh and Spanish instruction.

Fourteen kilometers up the Chubut River, the Gaiman has the Museo Histórico Regional which displays local Welsh culture and is located at the former central Chubut railway station. A number of tea houses in the town serve torta negra or cacen ddu , a Patagonian variant of the fruity and spicy Welsh bara brith te kake. Another 10 kilometers up the river is the meadow town of Dolavon, while Esquel and Trevelin, the latter name being Welsh for "mill town", continue to flourish near the Andes on the opposite side of the country.

Modern ties to the homeland

Welsh volunteers began traveling to Patagonia in the 1980s to help teach and preserve their language. The British Welsh Language Act of 1993 guaranteed that the tongue would receive equal treatment in the public sector. And the British Council established the Welsh Language Project in 1997 to preserve the tongue in the Chubut Valley, and sent language development officers annually to ensure Welsh functions in both formal and recreational settings. It is also based on a permanent Welsh education coordinator in Patagonia, who receives support from Argentina's native Welsh language.

The National Center for Welsh Learning awards three annual scholarships to Patagonians who choose to study Welsh at either Cardiff University or Aberystwyth University. In 2011, Wales' Urdd Gobaith Cymru Youth Voluntary Organization began planning voluntary trips to the Chubut Valley for members and young Welsh students. In addition, tour operators such as Teithiau Tango arrange Welsh-language tours around Patagonia.

In addition to the gleaming plaque currently pinned to Caernarfon to honor Lewis Jones, settlers' legacy has influenced writers such as British novelist Richard Llewellyn, who has written two books about the fictional Welsh character Huw Morgan who travels to Patagonia. Organizations such as the Arts Council of Wales present opportunities in Patagonia for Welsh musicians, filmmakers and photographers.

In 2010, musician Gruff Rhys from the Welsh rock band Super Furry Animals produced a film, Divorce , about his visit to the Chubut Valley to find distant relatives. In 2015, the Welsh playwright Marc Rees collaborated with the National Theater Wales and the Welsh-language TV channel S4C on a production in Aberdare, entitled 150 , about the settlers aboard the Mimosa.

That same year, the National Orchestra of Wales and the Welsh harpist Catrin Finch toured Patagonia, where the crowds welcomed them warmly and sang along in their language. Welsh Prime Minister Rhodri Morgan even visited Patagonia in 2001 to promote the country's languages abroad.

What the Welsh can teach us about cultural preservation

While Spanish-speaking Argentine culture dominates much of Patagonia today, the Welsh inhabitants of Puerto Madryn, Trelew, Rawson, Gaiman, Dolavon, Esquel and Trevelin continue to keep the language and traditions alive. Had Michael D. Jones and his followers not taken the first voyage across the Atlantic in 1865, their legacy might never have survived so long in their homeland. The Welsh gambled their livelihood by immigrating to the barren Chubut Valley with few natural resources, but the rewards for preserving their culture proved unparalleled.

And although the settlers ran the risk of assimilation again, their resilience combined with a willingness to adapt to the world around them led their culture to flourish in the toughest environments. Now, more than 150 years after Mimosa first reached Puerto Madryn, the Welsh heritage and lifestyle are great in the Chubut Valley, and cultural and linguistic ties continue to grow with Wales.

At the same time, Welsh Patagonia has become a social phenomenon in itself, demonstrating that change and diversification can actually prove beneficial to a culture. So if you ever get tired of the rapidly changing and evolving world around you, an international escapade may not fall under the craziest ideas. Wherever you go, remember to bring enough tea and cake with you on the trip.

Referenced Materials

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/The-History-of-Patagonia/

https://www.wales.com/about/language/history-welsh-people-patagonia

https://www.patagonia-argentina.com/en/the-welsh/

https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/welsh-language-in-patagonia-and-wales

https://www.swoop-patagonia.com/argentina/welsh-patagonia