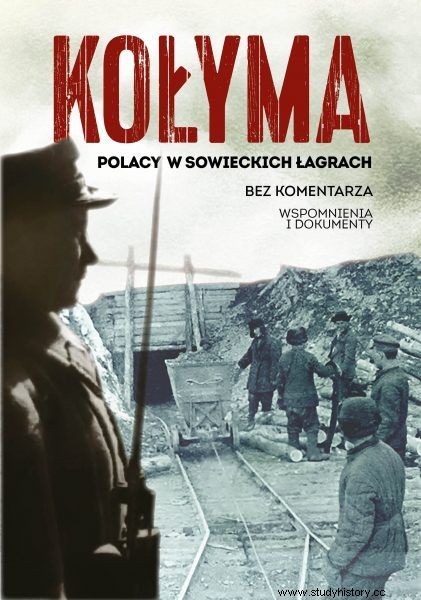

Frost down to minus fifty degrees. Starvation food rations. And slave labor, so hard that the standards imposed by the guards were almost impossible to meet. How did the Poles, who ended up in hell on earth - mines in Kołyma, cope?

For decades, Kolyma has been synonymous with death, hunger and slave labor. It was winter there for almost 10 months of the year - a real winter. Temperatures were down to minus 50 degrees . People, forced to live and work in these horrible conditions, fought for survival every day.

It all began in 1931, when, on the orders of Joseph Stalin, the Dalstroj company (Far Eastern Construction sites) was established, whose task was to develop the Kolyma river basin. The first labor camps were created there like mushrooms after the rain. Soon their entire system was functioning. The ice-bound and inaccessible port of Magadan made Kolyma, although a continental part of the USSR, an inaccessible island.

Increasing numbers of prisoners, both criminal and those convicted of so-called political crimes, began to be brought to the site in cattle cars. Representatives of various nationalities were sent to the Kolyma camps. There were Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Jews, Germans, Czechs, Armenians, Mongols, Japanese.

They were directed by sea through the port in Vladivostok or in Bukhta-Nakhodka. Workers were really needed - this inhospitable, uninhabited land hid real treasures . Gold, platinum, carbon, lead and uranium awaited man in countless amounts. And the prisoners who could be coerced into extracting them without regard to employment conditions were the workforce of the dream.

Many labor camps have been established in the Kolyma basin.

Poles came to Kolyma mainly in two periods. The first one covered 1940, when our countrymen were deported from Polish territories seized after the Soviet aggression against Poland. The second wave came after the Red Army re-entered in 1944.

Fight for survival

The work in the mines was very hard, beyond human strength. The elderly, the weak and the sick had no chance of survival. Even people in full health fell ill very quickly. Severe frosts, heavy snowfalls, snowstorms and, in addition, hunger rations resulted in the number of prisoners decreasing almost overnight .

“In winter, the frost was down to minus 60 degrees, and in summer the temperature rose to plus 45 degrees in the shade. In winter, without electric light, it was slightly visible from 11.00 to 13.00, and in summer the darkness lasted from 23.00 to 1.00 "- this was the life of the camp according to Telesfor Dembiński, whose memories are included in the collection " Kolyma. Poles in Soviet labor camps ” .

The day of the Łagrowicz people began with an appeal. Standing in the cold was unbearable. In addition, the barracks were searched several times a week. Then everything was turned upside down, and when something sharp, even a nail, was found, the owner of the object would receive several days of insulator. When there was no one to blame, all the inhabitants of the barracks suffered the consequences . The punishments were, for example, clearing snow from alleys, clearing up imported wood or forging ice at the toilets.

Under these conditions, death took a huge toll. Every morning, the bodies of prisoners who did not survive the night were taken out of the barracks. The dead were stripped naked - after all, everything the condemned was wearing belonged to the state. The bodies were tied with thick ropes and dragged across the snow to the place where there were pits for storing explosives. The corpse was thrown into these empty pits and covered with snow.

It is worth adding that the benign community was not homogeneous. robots worked in the mine's working brigades . They were obligated to meet the standards, the production of which influenced the received food rations. Those who avoided work or were too physically exhausted to do work were called income . In turn, odkazczyki they are camp "rebels" who refused to act - they spent most of their time in the penitentiary. pridurokowie, had the best life prisoners performing camp functions. They were the highest in the hierarchy and could turn the lives of others into a real nightmare.

Work, work, work

But what was the day of an ordinary robotiagi ? ? Dembiński, who worked in a gold mine in the town of "Bolszewik", described that the prisoners left the camp at 6 am. Before they got to their workplace, they had to walk 5 kilometers. At minus 50 degrees Celsius and dense fog, this road alone seemed deadly .

In winter, the main task of the inmates was to undermine the hills, under which there were golden sands. It was necessary to dig pits to a depth of 2 meters - only that the permafrost in this area was one meter, and sometimes even more. They used pickaxes, crowbars, shovels to dig these pits, and ammonite for undermining.

All prisoners knew the basic rule of survival in such weather conditions and for such work: you must keep moving . Lack of activity in such severe frost caused drowsiness and gradual freezing of the body. This is how the weakest died.

Prisoners often had to work outdoors, even in cold weather.

Sometimes the deposits themselves also turned out to be deadly. It was not by accident that the Aliaskite gulag, for example, enjoyed a bad reputation. It is enough to mention that the site of the tungsten ore mine was called "Death Valley" . The camp itself was divided into two parts by wires. In one of them there were (still) healthy prisoners, and in the other - the disabled and sick.

The dust of crushed quartz rock, sometimes so dense that miners were not able to see each other a few steps away, took away the health and lives of many inmates. After about two years of work in the mine, the prisoner developed a lung disease. It is not surprising then that the labor camp was often replenished with new batches of prisoners.

In search of gold

The work with golden sands also turned out to be murderous. Jadwiga Bisanz-Szmigiero was brought to the opencast gold mine "Marija Roskowoj" in June 1948. “I remember our first and terrible impression when we went to work in the morning and met the girls who left in March. We didn't recognize them. They were old, literally old women . Black faces burnt from the sun, dirty and emaciated "- she wrote in the memoirs in the book " Kolyma. Poles in Soviet labor camps ” . She described the tasks of the gold panning laborer:

There were cave-like holes dug in the side of the mountain. You always worked on a stream in order to have access to water needed to wash the output (...). Three people worked at the trough, one was throwing the earth from the shurf (excavation), the second was washing it, and the third was carrying the washed-out soil on the dump, and it was carried in iron, very heavy buckets.

Standards of work in the mines were difficult to develop even for able-bodied prisoners. Illustrative photo (1955).

Adam Kądziołka also worked on shurfs, i.e. a kind of well dug or knocked out in the rock in search of gold. He was arrested by the NKVD in August 1945. For belonging to the Home Army, he was sentenced to ten years of correctional and working camps. He landed in a labor camp with an idyllic - apparently - called "Spokojnyj".

What was the work of Kądziołka and thousands of other labor camps? Prisoners dug pits where they planted explosives. The rock crumbled thanks to them was brought to the surface with the use of wheelbarrows, which they pushed to the surface. Many inmates became crippled during the explosion .

Would a condemned man find gold by chance? Would he be lucky? Not necessarily. As Bronisław Radomski wrote, another of the co-authors of the collection “Kołyma. Poles in Soviet labor camps ” :

In the tundra you can meet, and quite often, the so-called gold nuggets. I have personally encountered the size of a large potato. However, no one will dare to get up, because it is the risk of imprisonment. Anyway, even if he picked it up and took it, what would he do with them? Who will he sell to? And who will he tell ? Such fear is a kind of a penal code.

By quality

The mines themselves were built haphazardly. The makeshift was dominant. Underground corridors were supported by a local tree - thin pines or mountain pine. No wonder that accidents were so frequent.

The food rations of the robotiags depended on the established standard. The photo shows the political prisoners of the Gulag.

Maciej Żołnierczyk (sentenced to 25 years in labor camps) told about the tragedy he witnessed. Well, a corridor collapsed in the mine. Several prisoners survived, but were cut off from the world. To get them out, it was necessary to open this corridor. The entire brigade would have to be involved. But was helping the prisoners in the interest of the camp authorities? Probably everyone knows the answer to this question:the prisoners were to extract valuable lumps of ore, and not waste time saving a slave's worthless life .

The soldier also recalled how ruthless the guards were towards those who were unable to meet the imposed daily norm. Inability to work could even amount to a death sentence:

(…) in the next grotto (...) there was a young German Nadwolżański, who, like Janek, drank hungry water. He did not meet his standard and in the morning a mermaid came. It turned out he did not do enough. Screams, curses began, I remember that puffy face of a young prisoner and the despair in his eyes .

Kriukov hit him with a kulak, the poor man fell to the ground like a chip, and then Kriukov and his son Shcherbakov started threshing the poor man with a shovel as if it were a sheaf of grain. After that everything died down, they told us to gather in the barracks and I don't know what happened to the poor man. I have never seen him after that.

What about those who refused to work? We know that such cases also happened. Punishment for reprimands there was a karcer-insulator. There was only a bunk for lying, of course without bedding. The prisoners received food once a day, and the portions were extremely economical. A little boiling water, 200 grams of bread and soup were brought in once a day.

The stove was lit only once a day for a while. The walls were covered with frost. It was allowed to lie down or walk. To survive, you had to move, do anything to stay awake. Sleep meant death .

USSR full of gold?

The convicts often wondered how much gold the Soviet Union gained from their slave labor. According to one of the Polish prisoners, there were about 40 mines in the Kolyma area. Each had two to six "gentle points." Each "gentle point" - a few gold-bearing plots. For one plot of land during the season, the standard was from 20 to 40 kilograms of gold per day.

If this is true, then the homeland of the proletariat could gain up to 10 tons of gold a day . And it must be remembered that there were still mines in Kamchatka, Sakhalin, on the Amur, the Urals and Kazakhstan.

Deadly frosts awaited the exiles. Illustrative photo (Vorkuta).

Another thing was that the mining statistics were commonly falsified. The camp administration was well aware that the work of prisoners was ineffective. But since the headquarters assigned high extraction rates to each camp, they had to be met. If only on paper .

Extracting precious ores from nature in such inhospitable Kolyma area took many lives. There are no exact numbers, only estimates. It is estimated that between 2 and 4 million prisoners died in all camps in the years 1937–1953. How many of them worked in the mines? We'll probably never know that.