Service in the Special Operations Executive, Churchill believed, requires character, willingness to pursue a noble cause and pirate bravado. He wanted SOE agents to show the French and other conquered nations that they were not alone and to prepare them for an uprising against the Nazi occupiers.

On a hot day in late August 1940, British secret agent George Bellows was working in the dusty Spanish border town of Irun, observing the chaotic arrivals and departures at a train station.

Spain was then ruled by another fascist dictator, Generalissimo Francisco Franco, and the country was full of Nazi informants, although he was officially neutral. Hundreds or even thousands of refugees poured across the borders from France every day, and some of them may have had vital information about what was happening under the yoke of the Third Reich.

Since Hitler's invasion and the evacuation of Dunkirk, British intelligence has almost completely lost touch with its closest continental ally. Most of the agents from the once vast network across France have fled, died or were burned.

London now depended on airborne reconnaissance and sketch reports by neutral diplomats or reporters to try to find out what Hitler and his allies were doing, knowing that a Nazi invasion through the English Channel was likely to come soon. Britain fought to survive but did so almost blindly.

France divided

Bellows' eye was caught by an elegant American woman doing something at the ticket office under the threatening gazes of Hitler, Mussolini and Franco looking down from large flags. The intrigued agent walked closer and began talking to a young woman who had just arrived from France and intended to travel to Portugal by train and from there by ship to Great Britain.

Bellows introduced himself as a salesman experienced in difficult war journeys and offered to help arrange the ride. Virginia told her amazing story to a polite companion (though she, as always, selected the information). Bellows found out that she had driven under fire on an ambulance, that she had traveled all over France alone, barely enduring the humiliation of surrender against Nazi Germany. That she had to cross the densely patrolled demarcation line that ran roughly along the Loire and divided the country into two zones.

Since Hitler's invasion and the evacuation of Dunkirk, British intelligence has almost completely lost touch with its closest continental ally. Most of the agents from the once vast network across France have fled, died, or were burned.

She explained in detail how quickly living conditions are deteriorating in the South (in the so-called Free or Unoccupied Zone) nominally ruled from Vichy by the unelected head of state, Marshal Pétain.

The Occupied Zone (north and west of France) was already under the direct control of the Germans stationed in Paris, and Virginia angrily mentioned curfew, food shortages, widespread arrests and incidents at the Renault factory where workers protesting against working conditions were lined up against a wall and were shot.

Special Operations Executive

Listening to this specific but passionate argument, Bellows was increasingly surprised by Virginia's courage on the battlefield, her sense of observation, and above all, her immense desire to help the French in battle. Trusting his instincts, the agent made the most important decision in his life, which was to restore hope for a possible Allied victory in France.

When he was saying goodbye to Virginia, he surreptitiously gave her the phone number of a London "friend" that would help her find a useful job - he also insisted that she use her contact as soon as she arrived . Even if the US State Department underestimated her merits, Bellows knew he had just met someone of exceptional strength.

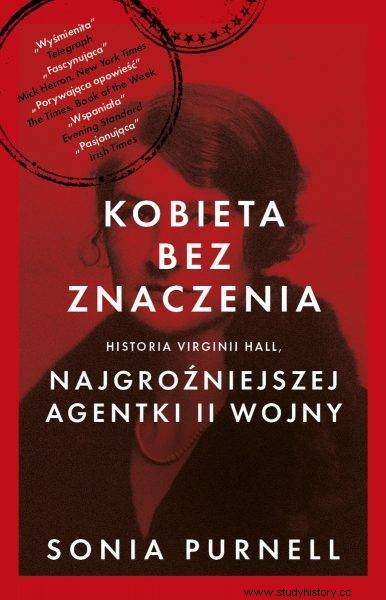

The text is an excerpt from Sonia Purnell's book “A Woman of No Meaning. The Story of Virginia Hall ”, which has just been released by Agora Publishing House.

Bellows did not reveal anything else and, judging from the visa application, Virginia assumed that after her arrival in England she would drive the ambulance again. Meanwhile, the phone number belonged to Nicolas Bodington, a high-ranking officer in the independent F (French) Section, the new and controversial British secret service.

The Special Operations Executive was formed on July 19, 1940, the day Hitler gave his triumphant speech at the Reichstag in Berlin, boasting his victories.

In response, Winston Churchill personally ordered SOE to "set fire to Europe" by sabotaging on an unprecedented scale, subversive and espionage. He wanted SOE agents (actually more special than espionage forces) to find a way to ignite the flame of resistance, show the French and other conquered nations that they were not alone, and prepare them for an uprising against the Nazi occupiers.

With a new form of irregular warfare - as yet undefined and untested - they were to prepare for the distant day when Britain could once again place its troops on the continent. Even if this new guerrilla version of the fifth column went against Queensberry's rules on international military conflict (modes of operation, ranks and uniforms), it was because the Nazis left no other choice.

Service in SOE, Churchill believed, required character, willingness to pursue a noble cause and pirate bravado. But SOE - and no wonder - couldn't find agents brave enough to operate clandestinely in France without emergency support. Nobody seriously considered women to be suicidal on a mission. Nevertheless, Bellows decided that the American he met at the Irun station was exactly the kind of person SOE needed.

Source:

The text is an excerpt from the book by Sonia Purnell “A woman of no importance. The Story of Virginia Hall ”, which has just been released by Agora.