After the defeat in September and the defeat under the skies of France, Polish airmen gained the opportunity to retaliate against Germany, defending England. On September 15, 1940 - at the height of the Battle of Britain - they were recognized as one of the best and most effective fighters during World War II.

The Poles were, in the eyes of the English, soldiers of the defeated army, untrustworthy sowers of defeat and defeatism. And defeatism in the UK was quite high. They wondered why fight again in a foreign cause, giving a blood tribute as in World War I, again on French soil.

The appearance of Poles only made it difficult to get along with Hitler in the manner of Neville Chamberlain. Until France fell. It was only then that the British realized that it was a completely different type of war that had never happened before (...).

"Hussar" wings

When France fell after 44 days, people began to look at Poles, if not with admiration, it was too early, then with genuine respect which is quite rare among English people. Poland also withstood 44 days with two enemies of equal potential, namely the Third Reich and the First Soyuz, i.e. the Soviet Union.

The English and the RAF command initially did not want to agree to the creation of a sovereign air force and offered the Poles to join the RAF immediately, just like the Commonwealth pilots. It was not until June 1940 that Winston Churchill, Chamberlain's successor, made small concessions.

This was enough to on June 11, 1940, to conclude a Polish-British aviation agreement , according to which Polish airmen took two oaths:in English, to loyalty to the British crown and its king, and to the Republic of Poland.

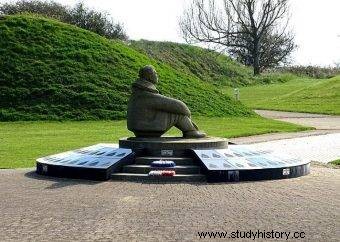

When in 1993 the monument to the Battle of Britain was unveiled in Capel-le-Ferne near Folkestone, the emblems of the Polish 302 and 303 squadrons were missing. It was only later that Polish squadrons were added

On their uniforms they kept Polish Eagles and aviation "Hussar" wings around him, the "POLAND" badge on the left sleeve, and at the airports where Polish squadrons were stationed, the Polish flag waved right under the RAF flag, while the hulls were painted with Polish chessboards ( …).

300, 301, 302, 303

At the time of the defeat of France, on June 24, 1940, 2,226 Polish pilots, including as many as 243 officers, were already serving in the RAF, but it was not until July 1, 1940 that the first Polish bomber squadron No. 300 "Masovian Land" was established in Bramcote in Leicester County. under the command of the pilot Wacław Makowski.

Three weeks later, another, 301 "Pomeranian Land" named after Defenders of Warsaw under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Roman Rudkowski from the former 11th Fighter Regiment from Lida. At the airport in Leconsfield near the city of Hull, the third squadron 302 "Poznań" was established. This one was under the command of Mieczysław Mumler.

The text is an excerpt from Krzysztof Jabłonka's book “100 Polish Battles. On land, sea and in the air ”, which has just been released by the Zona Zero publishing house.

Finally, at the Northolt airport near London, another (already fourth) 303 Fighter Squadron "Warszawski" was formed. Tadeusz Kościuszko, whose first commander was Major Zdzisław Krasnodębski (...).

Harbingers of disaster

The Poles did not catch the battle for Britain, as the British themselves call it, only in the second phase, when the command realized that the losses were so great that anyone who knew how to fly was better than none, even if he was Polish. (…)

"The devil himself would be good, let alone the Poles" - is the opinion of one of the RAF commanders. The Poles, these harbingers of defeat, were simply supposed to patch the holes in the local staff shortages until the flight schools release freshly trained British pilots.

On August 19, 1940, the pilot Krasnodębski took to the air for the first time on a brand new Hurricane. "(...) The only thing missing is ... Germans who could be shot freely, Krasnodębski probably thought. They have already encountered them on the first training flight (…).

"Beat the German until the chips fly"

The course was not over yet, when the pilot, Lieutenant Ludwik Witold Paszkiewicz, reported that he could see German machines on the left side (...). How a hawk fell on the wings of the sluggish bombers, bringing death to the people of Albion.

I noticed a plane with two fins (a telltale sign that this is German) turning towards me. When he saw me, he started to run away. I dove after him. I started firing some 200 meters down its hull.

As I approached the second attack, I saw the pilot parachute out of the interior and his plane hit the ground without leaving the dive. This was the first time in my life that I was shooting an enemy plane.

Jan Zumbach, ps. "Donald Duck", "Johan" - lieutenant colonel, certified pilot of the Polish Army, lieutenant-colonel of the Royal Air Force.

Krasnodębski, as the commander of the entire 303 Squadron, also had to set an example of courage and efficiency. He was amazed at the ease of controlling the plane. " How it took a sweat to turn on our peels, and here it was enough to turn the rudder and the gyrocompass showed all the necessary settings. With such equipment, you can beat a German until the chips fly, "he thought.

Indeed, already on its third combat flight, chasing the fighter, he caught it in the sight. He accelerated and unpacked the whole series into it, until it burned in front of his eyes (...).

England saved by… accident?

The climax of the Battle of Britain came on September 7, when the entire German armada, consisting of over a thousand aircraft, was flying in one direction towards London.

Many scholars speculate that Britain survived somewhat by chance, to which, of course, must be added the incredible bravery of its defenders. Well, one of the night crews of the German bomber lost its target and on its way back, looked for a place to drop its bombs somewhere.

Since the blackout was very strictly enforced by the police, and each streak of light was treated as a sign to the enemy, as it used to be, German bombardiers dropped bombs over a darkened area in what turned out to be a poor suburb of London. There were civilian casualties among the poorest. The most important thing, however, was that the unwritten rule that large cities would not be bombed was broken in this way.

Immediately on Churchill's orders, a retaliatory expedition to Berlin was launched. Although its military effect, due to quite good German defense, was negligible, the political and strategic effect was electrifying.

Adolf Hitler boiled with indignation (...). It was therefore decided to bomb London so that the British themselves would ask for peace, which the Reich would graciously grant them under the threat of additional bombing. But one had not to know British pride to come to such conclusions (...).

A game for everything

On that day, September 7, 1940, the RAF picked up all the machines at its disposal. Needless to say, it was a game for everything (…). The British won, and Polish aviators played the role of a useful bee in this clash of world powers, which with its weight outweighed the scales on the side of those who defended independence.

After that day, the Germans finally gave up the "Operation Seelowe" (sea lion), that is, the landing on the Islands. Great Britain survived. "Poles are all courage" - wrote Dorothy Thompson, an American press reporter about them.

She was echoed by King George VI, who visited the Poles on September 26, 1940, while they were waiting for the start. The king was just talking to the pilots when the navigator telephone operator, ignoring the king's presence, roared, "Three hundred and three to start!" Alarm". The airmen, not saying goodbye to His Majesty, rushed to the planes, only to be in the air after a while.

The text is an excerpt from Krzysztof Jabłonka's book “100 Polish Battles. On land, sea and in the air ”, which has just been released by the Zona Zero publishing house.

The king liked the start of the Poles very much and asked the airport crew to send him the result of the fight on that day. A report was awaiting him by the time he returned to his Buckingham Palace. It read:“Polish 303 Squadron has just destroyed 11 enemy aircraft, probably one. Own losses:zero. ”

As a token of appreciation, on the following day the pilots received a personal photo of the king with a personal dedication to each of them. In fact, as many as 15 planes were shot down, but also on that day the first airmen:Ludwik "Paszka" Paszkiewicz and the young sergeant Tadeusz Andruszko (...).

Battle of Britain, Wales, Scotland and Ireland

"Perhaps," said the RAF commander, "if not for the help of a great team of Poles and their incomparable bravery, I would hesitate to say whether the outcome of the Battle of England, Wales and Scotland would be the same ... But what will remain with us forever, is our appreciation and our gratitude for the help given to us in times of great need and our admiration for the incomparable bravery of those who have shown us this help. ”

(...) the successes of Polish squadrons amounted to 25 percent. all shootings of the RAF, of which the 303 Squadron fell 127 certain and the second as many probable, i.e. 12.5 percent. the whole, which was anyway the most victories in the entire Imperial Air Fleet, despite efforts to reduce them to British measures (...).

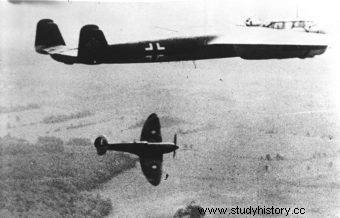

RAF Spitfire attacks Do 17 Dornier formation during the Battle of Britain

It is worth adding that the location of "Polish airports" in Wales in Pembrey, Ackington and Renfrew in Scotland extended the battle of Wales and Scotland. Moreover, the Poles, stationed in Scotland until the end of the war, became the natural defenders of its coast against the attempts of the Germans who planned an attack on Scotland from Norway (...).

The battle for Ireland, including Northern Ireland, was of a completely different nature. (...) Polish airmen defended Ireland against German bomber pilots who, wanting to escape from the battlefield, took a "safe" direction to Ireland to drop bombs there and return home without burden.

Polish pilots defended Ireland against this practice by chasing German machines to the end before dropping their bombs either over the Irish Sea or over Ireland. In both cases, Poles during the war were perceived by the Irish as defenders of their heaven as well.

Loss account

Ultimately, by the end of October 1940, when the end of the Battle of Britain was announced, and the Germans stopped their tactics to exhaustion, they lost 1,733 planes and about 650 were damaged. Let us add that this equates to the loss of over 3,000. pilots and navigators captured, not counting bomber and rifle personnel knocked down over the Isles.

During this time, the RAF lost 1,087 aircraft and 450 were damaged, fortunately their pilots survived and resumed service.

Source:

The text is an excerpt from Krzysztof Jabłonka's book “100 Polish Battles. On land, sea and in the air ”, which has just been released by the Zona Zero publishing house.