It wasn't supposed to look like this. A superpower with huge resources and modern weapons should easily deal with the poor, starved Vietcong guerrillas and the army from the North. However, it did not happen - after all, Washington with its tail tucked up had to withdraw its army. How is that possible?

1954 was a breakthrough for Vietnam. In the spring, the decisive Battle of Dien Bien Phu took place. Selected French units for 55 days desperately defended their base against the siege of the communist Vietnamese partisans - Việt Minh. However, against the outnumbered enemy forces, the French had no chance . This is how their reign of nearly one hundred years ended.

The question quickly arose, what should the country look like now? It was hoped that the answer would come from a conference held in 1954 in Geneva, Switzerland. It agreed that Vietnam would regain independence, but would be temporarily divided along the seventeenth parallel. Việt Minh and his leader, Ho Chi Minh, led the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRW) with Hanoi as its capital, while the Republic of Vietnam with its capital in Saigon became the seat of a separate French-backed Ngo Dinh Diem government.

The agreement stipulated that elections would be held in 1956 that would unite the country. But when it became clear that Ho Chi Minh's communist government had overwhelming support, Ngo Dinh Diem backed away from his promise of a democratic settlement.

"We have a responsibility to prove our power"

The beginnings of Washington's involvement in the Vietnam conflict date back to the early 1950s. President Harry Truman sent weapons and advisers there, and helped train French fighting communist guerrillas.

Initially, the Americans were only involved in the role of advisers and trainers.

With Paris losing control of the country, Truman's successor, Dwight Eisenhower, still chose not to send US combat troops. At the same time, however, he doubled the shipments of weapons and the number of advisers. He himself was a follower of the "domino theory". In her mind, if the communists took power across Vietnam, it would cause a chain reaction and more countries in the region would fall into the red hands.

In 1961, John F. Kennedy became the head of the United States. The beginnings of his presidency were not very pleasant. The disaster at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba tarnished his image. He felt he had to show strength - and so it did. His environment decided that South East Asia would be the best place to confront communism. "We now have a responsibility to lend credence to our power and Vietnam is exactly the place where we will do it" - said the president.

The number of American advisers supporting the Army of the Republic of Vietnam gradually increased. In mid-1962, there were as many as 12,000 people. It would seem that ARW, with better equipment, aviation and the help of allies, would deal with the enemy. Nothing could be more wrong. Vietcong, step by step, achieved successive military successes. The successor of Kennedy shot in 1963, Lyndon B. Johnson, had no choice but to continue the policies of his predecessors. But it didn't do much.

Johnson faced a difficult choice. He could allow the slow fall of the Republic of Vietnam ... or he could send his army into battle. The second option won. The US, however, needed an excuse to justify its military commitment. And they found him.

At the beginning of August 1964, the American destroyer USS Maddox, operating 30 nautical miles off the coast of the northern part of Vietnam, i.e. in international waters, was shelled by DRW boats. Two days later, on the night of August 4, Maddox and another US destroyer sent reports to the base that they had been attacked again.

President Johnson needed no more. He persuaded congressmen to grant him permission to escalate military action against North Vietnam. The United States thus became embroiled in a war it could not win.

Failed bombings

On March 2, Operation Rolling Thunder began. Its purpose was, among other things, to destroy the enemy's infrastructure, industry, air defense and supply routes. The number of US aviation stocks is staggering. In 1965, planes made 25,000 flights, in 1966 - 79,000, and a year later - 108,000. In total, about ... 1.6 million tons of bombs have been dropped in the areas of South and North Vietnam . The effects of these actions were catastrophic. Both countries were ruined and around 100,000 people died. The Americans alone lost over a thousand machines. Meanwhile, the communists remained very strong .

On January 30, 1968, Washington soldiers were completely taken by surprise by the attack of the North Vietnamese Army (AWP) and the Vietcong Army. In preparing the offensive, Ho Chi Minh showed remarkable cunning. He used Tết, the most important holiday of the Vietnamese, celebrated for several days. During his time, he announced a ceasefire to lull the opponent's vigilance.

Fights broke out in the largest cities, south of the demilitarized zone, which was marked by the 17th parallel. First, artillery shelled the Americans, then the Vietcong infantry entered. Initially, the guerrillas were extremely successful; suffice it to say that fierce fighting took place in the streets of Saigon. However, the success quickly turned into a failure. The strength of Vietcong was the jungle. They could lash out quickly, constantly harass the surprised enemy, but they had to retreat almost immediately, because in the open field they had no chance of winning.

In the open ground, Vietcong had no chance against the Americans. However, he was strong enough to harass them with quick, accurate surprise attacks.

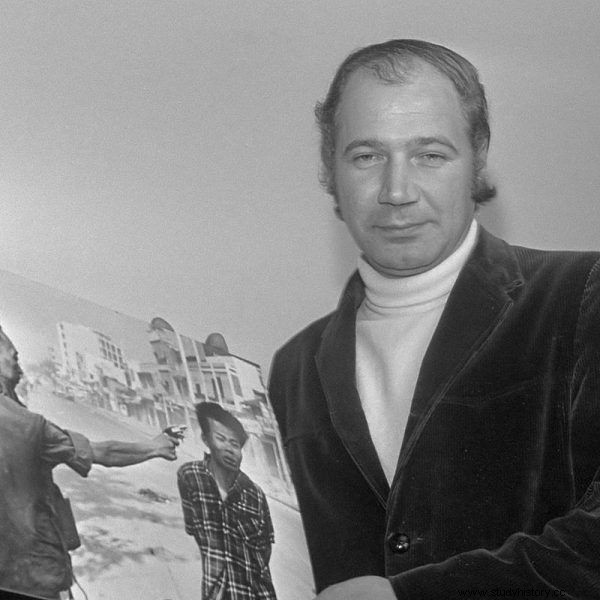

The Western world from the Tết offensive remembered one photo taken in Saigon on February 1, 1968. It shows General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, the head of the South Vietnamese police, shooting in the head of a handcuffed prisoner - a Vietcong partisan. As he writes in the book "Hue 1968. Vietnam in the blood" American journalist Mark Bowden:

The photo was taken at death, the victim's face grimaced in pain and shock. No attention was paid to the fact that this prisoner had executed many people in cold blood that same morning. The photo itself told a simpler, more brutal story that was enthusiastically received by opponents of the war.

The offensive ended in February with a military victory for the US and South Vietnam. But morally, Wieczong was on top. It turned out that the guerrillas were able to surprise the power and inflict heavy losses on it. After the Tết offensive, Washington could no longer maintain that the war could be won quickly and easily. There was no end in sight. From then on, there was no longer a debate about how to win, but about how to get out of Vietnam.

In the fall of 1968, Johnson announced that his country was stopping air raids on North Vietnam. At the same time, he called for negotiations. In practice, Johnson's plans had to be implemented by his successor - Richard Nixon. The main question was how to get out of this horrible war with honor.

The Nixon administration created three scenarios. The first was that the US would announce a withdrawal from the war, and it just did. No additional conditions. According to the second, the attack on the Viet Cong had to be intensified first, and then talks with Hanoi had to be started. And finally the last option - "Vietnamese" the war . The idea was to help the South Vietnamese army financially and by arming itself to defeat the communists. And it was the solution that won.

A photo of the execution of one of the communist guerrillas, taken by Eddie Adams, went around the world.

Opposition in the country

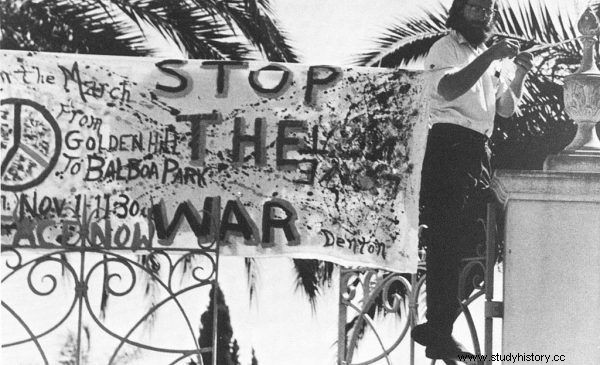

How did it happen that over the course of several years - from their involvement in the conflict until 1968 - the Americans changed their attitude to war so radically? The first flashes of the crisis appeared as early as 1964. In August this year, more than 20,000 people took to the streets of Washington. They expressed their support for the two senators who voted against the Tonkin Resolution, which gave the president the right to start military action.

The "campus rebellion" also began. During rallies combined with lectures, students said that every war is evil and that the US intervention in Vietnam should be ended quickly. Gradually, the protesters and opponents of American politics left the university walls and took to the streets. The young people saw no reason to die in the Vietnamese jungle.

Initially, the anti-war movement was dominated by pacifists, leftist radicals and opponents of nuclear weapons. Over time, other groups joined the movement - intellectuals, sportsmen and musicians. It is worth recalling that boxing genius Muhammad Ali himself was fined, stripped of his title and sentenced to prison for refusing to report for conscription.

In 1967, the famous March on the Pentagon took place, in which as many as 50,000 participants took part. The world media circulated a photo of a young pacifist demonstrator putting flowers into the barrels of rifles aimed at him. This protest, however, had a further bottom. The radicals leading the crowd attempted to attack the Pentagon. The army's reaction was immediate. There were clashes, after which a thousand people were arrested. Many commentators later stated that the march was a turning point in all anti-war action.

In 1968, President Johnson himself said that the American people had not been so divided since the Civil War . Indeed, a fierce dispute arose among the Americans. Some called the operations of troops in distant Asia genocide, others - the defense of freedom. In 1969, the anti-war movement reached its peak. October 15 and November 15 were declared Moratorium Days. Hundreds of thousands of people took part in marches and protests throughout the United States.

Media opposition

The Americans learned the true picture of the war in Vietnam from their war correspondents. In previous conflicts, the correspondents were considered part of the crew, so they were allowed to go anywhere as long as they could arrange transport and an interpreter. Reporters joined the military columns and went directly to the front. This time, however, what they saw and heard from ordinary privates and young officers there was very different from what was served by official propaganda.

In the late 1960s, a significant proportion of correspondents reported that the war was going wrong, that there was no chance of victory, and that the US military's actions to pacify the villagers were ineffective . In August 1967, a text by Jonathan Schell appeared in the New Yorker. The material made an electrifying impression on the Americans. The journalist described an attempt to cleanse two provinces of South Vietnam of Viet Kong influence.

Schell described that the entire military strategy was based mainly on destroying villages and driving the inhabitants to high security camps . This method of fighting was extremely ineffective. When he himself asked for permission to visit one of the "pacified" villages, he was informed that none of them was safe enough. Mark Bowden in "Hue 1968. Vietnam in Blood" says:

The journalist also described the racism of American soldiers who bragged about torturing and murdering prisoners, throwing out guerrilla suspects from helicopters and shooting civilians from the air - boasting that they could to distinguish Viet Cong from the farmers even in advance.

Protests in the US against the war grew stronger - the administration could not escalate the conflict indefinitely.

The Americans are already at home. But what next?

In the mid-1970s, any healthy male who graduated from high school in the US and had no plans for further education was eligible for conscription. Many of them saw their future in the army. Moreover, many of them had fathers, uncles who fought in WWII or in Korea. When they returned, they were presented as conquerors, heroes, defenders of God and the homeland. Everything changed after 1968. Soldiers returning from Vietnam, often permanently mutilated, were not greeted with a loud voice. There were no flowers, orchestras playing, and no flowers. There was shame, sadness and regret. It's a pity their state has failed.

As for Vietnam itself, on January 27, 1973, the US-Vietnamese treaty was signed in Paris. The Americans abandoned their allies. The Vietcong was moving south without any obstacles, occupying other areas of its neighbor. On April 30, Saigon fell into the hands of the communists. All of Vietnam was already theirs.

The balance of the victims of the Vietnamese carnage arouses emotions to this day. Between 2.5 and 3 million Vietnamese and nearly 60,000 American soldiers were killed.