From a paranoid state of tension to an uncontrolled explosion. These were the first hours of the uprising, which went down in history as the Greater Poland Uprising. The center of the Polish-German struggle for the membership of Greater Poland was Poznań. This is where the first shots were fired and the first victims were fired.

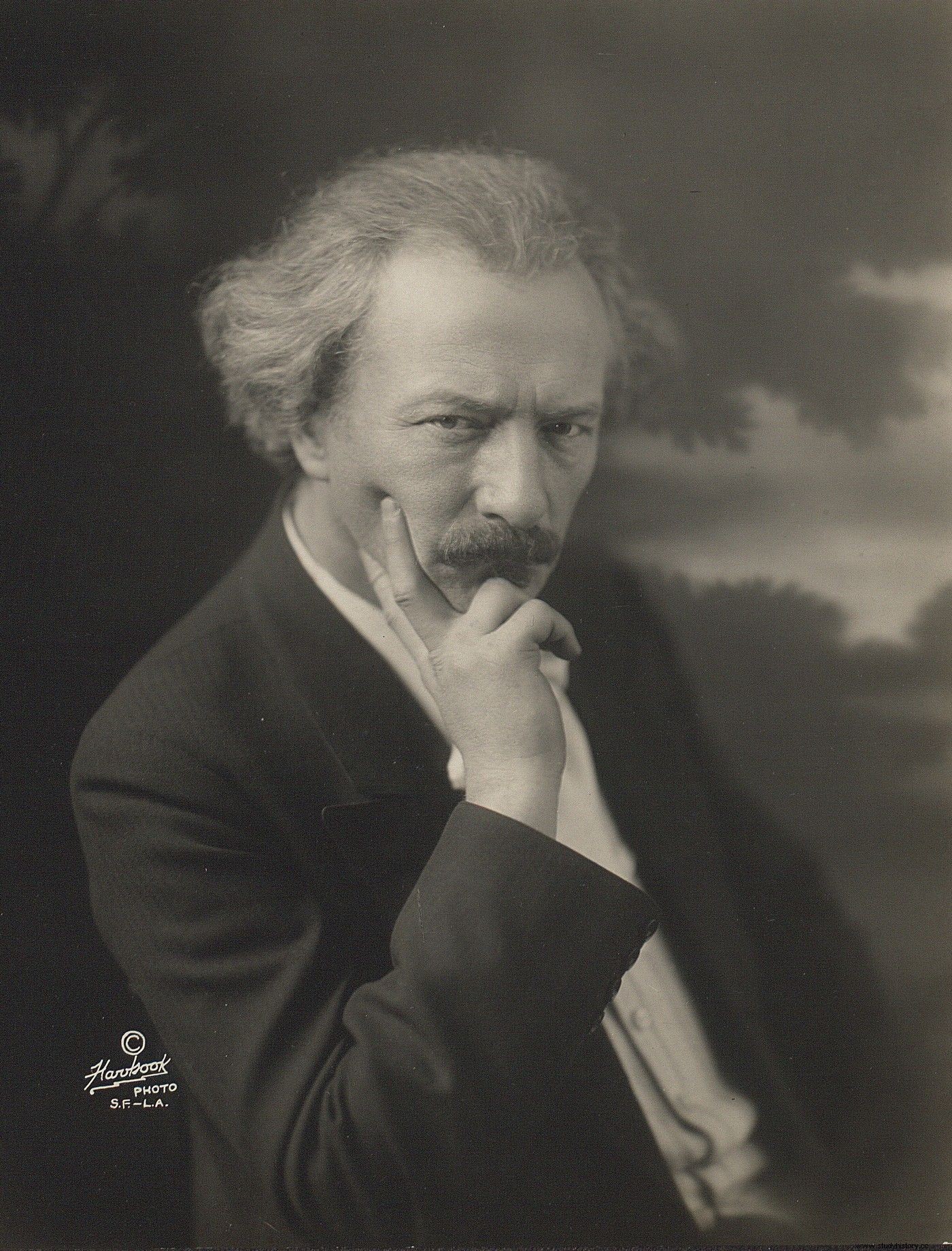

Ignacy Jan Paderewski arrived in the capital of Greater Poland on December 26 in the evening. Later he emphasized that he was surprised by the reception that the people of Poznań had given him. He must also have been excited when from the window of the Bazar hotel he noticed tens of thousands of people from Poznań waiting patiently for his speech. The artist had a fever, freshly ill, but he did not intend to ignore the audience. He stood in the window above the main entrance to the Bazaar, and in a moment his first words were to be heard.

The situation in Poznań was tense. There were rumors of an influx of more and more soldiers from the invader. Everything indicated that the Germans wanted to deal with the Poles by armed forces. The Polish government in Warsaw officially broke off its barely established diplomatic relations with its western neighbor. The Master must have known that a great deal depended on him now. If he said too much, he could explode immediately. As a diplomat, who believed in friendly solutions, he could not be too encouraged to fight.

Dear representatives of Wielkopolska!

Dear compatriots and compatriots.

Sisters and brothers!

With these words the speech began historically. Paderewski thanked for the touching greeting, emphasized his apoliticality and willingness to reconcile all Polish patriots:"We are all children of one Mother and, as long as each of us fulfills his duty, we have equal rights to her fair care." The speech was patriotic but also restrained.

To protect Paderewski

The next day, December 27, 1918, the press published the master's speech, although it had already managed to travel all over Poznań. The state of tension was still perceptible, but it seemed that the master's attitude cooled the mood a bit and that at least on that day, nothing important would happen, especially since Paderewski himself - who was covered by his health condition - did not leave the hotel room.

Paderewski was welcomed by tens of thousands of Poznań residents on December 26, 1918.

Both German youth organized their pickets in the city, in front of the Municipal Theater, and Polish youth, in front of the Bazar hotel. However, they were far from rioting. The situation changed in the afternoon. The Germans, wanting to emphasize their ties with the city, decided to organize marches and rallies that would match Paderewski's welcome. The mere singing of nationalist songs has not yet enraged Poles, but the attempt to organize a German demonstration going to the Bazar Hotel was quickly interpreted as a provocation.

Meanwhile, the Germans did not intend to withdraw. The ranks of their march were mainly civilians, but there were also armed soldiers. The community of about 2,000 moved from Zwierzyniecka Street and slowly headed towards Paderewski's temporary seat. In the city center, the Germans shouted anti-Polish shouts at the Bismarck monument; then they began to devastate Polish premises and institutions. Among others, Góralski café at Wilhelmowska Street and the headquarters of the Commissariat of the Supreme People's Council.

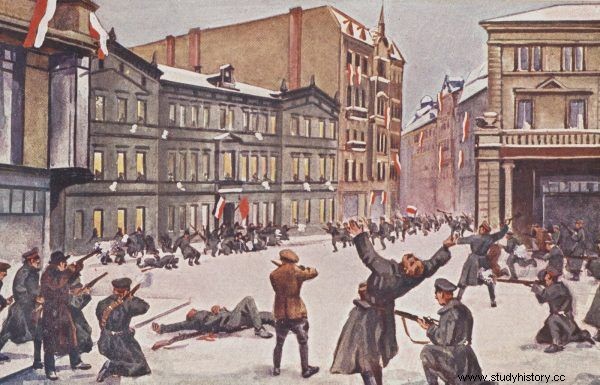

The Germans did not stop there. They torn off and destroyed the flags of Poland and the Entente countries. The next incidents were to take place outside the Bazar Hotel, which was already approached by demonstrators. In response, the Poles surrounded the building with a cordon of units of the People's Guard and the Guard and Security Service. Support was also provided by the Polish Military Organization of the Prussian Partition (POWZP). It was 5pm when both sides faced each other. Then the first shot was fired.

From Chaos to War

A hellish tumult ensued. To this day, it is not known who the man who pulled the trigger first is unknown. It didn't even matter if it was a Pole or a German. The fight flared up. More shots were fired, grenades exploded. The first fatalities also fell quickly. In those chaotic minutes, no one really had a chance to control the situation or even identify the enemies. There was also no clear command, and historians still argue about which Pole made the most important decisions.

Only after two hours did the total confusion begin to turn into any organized fight. The fights were by no means waning. They spilled all over the city, giving rise to the Polish uprising. If somewhere there was a relative peace, it was only in the Bazar Hotel itself, in the immediate vicinity of Paderewski. The artist did not even see that a decisive uprising against the partitioner had begun. Hotel staff believed that these were just isolated incidents and riots; this was also communicated to the guests.

Meanwhile, the enraged Poles moved to the headquarters of the hated German police. There was a sharp exchange of fire with the Germans in front of the building, but the advantage was clearly on the side of the insurgents. Soon, the Poles also managed to take over the station, post office and means of communication. As a result, news about the uprising could reach the rest of the region and - to Warsaw.

Polish conspirators, incl. from Gniezno, Kórnik and Września began mobilization. Some of the fighters quickly reached Poznań. At the same time, the Germans organized support by rail transport. However, before they even attempted to regain the initiative, the Poles targeted the most important points in the city. Fort Winiary and Fort Grolman were among their captures.

The Old Market Square was taken almost without a shot. However, heavy but victorious fights took place in Jeżyce. Intensive battles were also fought in Wielki Garbary, where the Germans shot Poles from the windows of their apartments, and even from Protestant churches. Similar clashes took place at Grobla Street or near the Rzymski Hotel. Nevertheless, the Poles successfully liquidated the German resistance. There was disorientation among the Germans; they also clearly lacked supplies.

The first day of the uprising ended with the undisputed victory of the Poles. However, those who expected that the entire city would immediately pass into the hands of the rebels were wrong. The brake was unexpectedly pressed.

The assault on the headquarters of the German police in Poznań in a drawing by Leon Prauziński.

Fight or not?

To the surprise of many combatants, the most important Polish organization in Poznań, i.e. the Supreme People's Council, actually from the very beginning tried to limit the fighting. Its representatives decided that if the uprising extended its scope, it would be impossible to control and the Council would be pushed to the sidelines. Moreover, there was a concern that the insurrection could turn into an open, unlimited Polish-German war, for which Poles were by no means prepared.

The threat was serious, because hundreds of thousands of German soldiers were still stationed in the Warsaw area, waiting to return to their homeland. Hence, on December 28, a conciliatory decision was made to establish a Polish-German City Command. From now on, weapons were not allowed in Poznań, and a state of emergency was introduced.

Both Polish and German institutions and organizations began to regret the events of the previous night. This made the insurgents bitter, who had no intention of withdrawing from the fight. In the evening, an extraordinary conference was called at the Bazar hotel, and all national and independence trends were invited to participate.

Members of the Supreme People's Council did not want to escalate the conflict with Germany.

The Supreme People's Council was represented by Wojciech Korfanty, in turn, mainly Mieczysław Paluch spoke on behalf of the insurgents. Supporters of the continued fighting realized that the authority of the Council must remain intact for the good of the whole country. The compromise was to appoint an officer who would rule over lawlessness.

The commander was Stanisław Taczak, captain of the Polish Army, who was only passing through Poznań. The historian Janusz Osica wrote about him:“He was a man who had to struggle to get to higher positions and higher dignities. Ambitious, educated […]. He started the organizational work with great energy. Practically speaking, Taczak also often taught amateurs the basics [...] of fighting strategies, which were very important. His general tactical directives were highly appreciated because they were practical and based on military experience.

The brief détente was coming to an end; it was becoming clear that the fighting had to resume. Meanwhile, Ignacy Paderewski - a man who might not have started the uprising, but at least unintentionally pushed the people of Poznań to join him - left the city. On the night of January 1, 1919, he left for Warsaw.

You can read about the victories of our weapon in our latest book "Polish triumphs" . It is the perfect gift for any history buff. Click and buy with a discount on empik.com.

The new year was to bring a decisive start. Most of the city was already in the hands of Poles, but the Germans still controlled the key point of resistance:the Ławica air station in the western part of Poznań.

The last confrontation

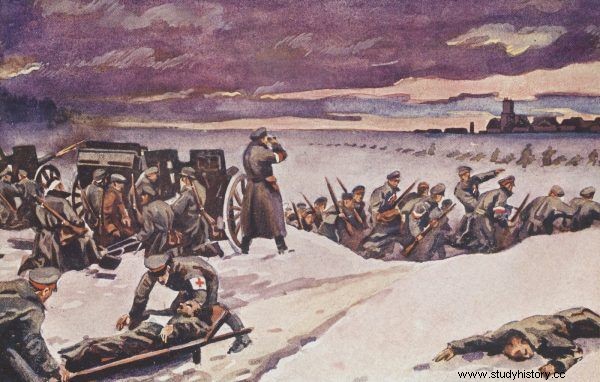

Taking over Ławica was not an easy task. The airmen who resisted the Poles threatened to bomb the city and blow up aviation ammunition stores. The plans for the attack were made by the Guard and Security Service, but the final decision rested with Stanisław Taczak. He took it up after long debates at the Royal Hotel at Święty Marcin 38, where the main staff was located.

Before the attack began, the station was cut off from the power line. The telephone cable was also broken. Joined forces include The Guard and Security Services, artillery and the Polish Military Organization set off to Ławica at 2 a.m. on January 5 to 6. Stanisław Taczak appointed Andrzej Kopa as the commander of the action.

The airport was surrounded by Poles. Before the fighting broke out, parliamentarians were sent to the Germans to convince them to withdraw from resistance. The garrison members, although aware that they were trapped, refused. Then artillery opened fire on them. The insurgents launched an attack. At eight o'clock it was over. The airport was in Polish hands, and only three people died in the fighting - two Germans and one Pole.

The capture of the airport in Ławica. A drawing by Leon Prauziński.

The Germans did not manage to regain Ławica, although planes from the Frankfurt base even tried to bomb the facility. Meanwhile, the insurgents seized the airship hall, where the aviation equipment was stored. It will soon become one of the foundations for the emerging air force of independent Poland.

On January 6, 1919, the fighting for Poznań ended. The exact losses of both sides are unknown. Poznań was subordinated to the Poles. After conquering the city, it was time to fight for the whole of Wielkopolska. The uprising continued and was to turn out to be the first successful national uprising since the partitions.

***

You can read about the successes of our weapon in the book “Polish triumphs. 50 glorious battles in our history ” . Learn about the clashes that changed the course of history with this richly illustrated publication. From victorious fights in the times of Bolesław the Brave, to fierce battles in World War II. Successes that every Pole should remember. Buy today with a discount at empik.com ,

Find out more:

- Czubiński A., Greater Poland Uprising 1918-1919. Genesis, character, meaning , Kurpisz, Poznań 2002.

- Giziński J., 1918 Greater Poland Uprising. The victorious end of the longest war , Axel Springer Polska, Warsaw 2008.

- Grot Z., Czubiński A., Greater Poland Uprising 1918-1919 , Poznań Publishing House, Poznań 2006.

- Łukomski G., Pola B., Powstanie Wielkopolskie 1918-1919. Combat operations, political aspects, calendar , Adiutor, Koszalin 2005.

- Greater Poland Uprising , ed. J. Macyszyn, Bellona, Warsaw 2006.

- Rezler M., Greater Poland Uprising 1918-1919 , Rebis Publishing House, Poznań 2016.