He was a stranger to the English, and his pastimes - hockey, baseball and rattlesnake shooting - were not respected in the UK. However, he only learned the importance of cultural distance when he was assigned to the 303 Squadron. And he began to fly with the Poles.

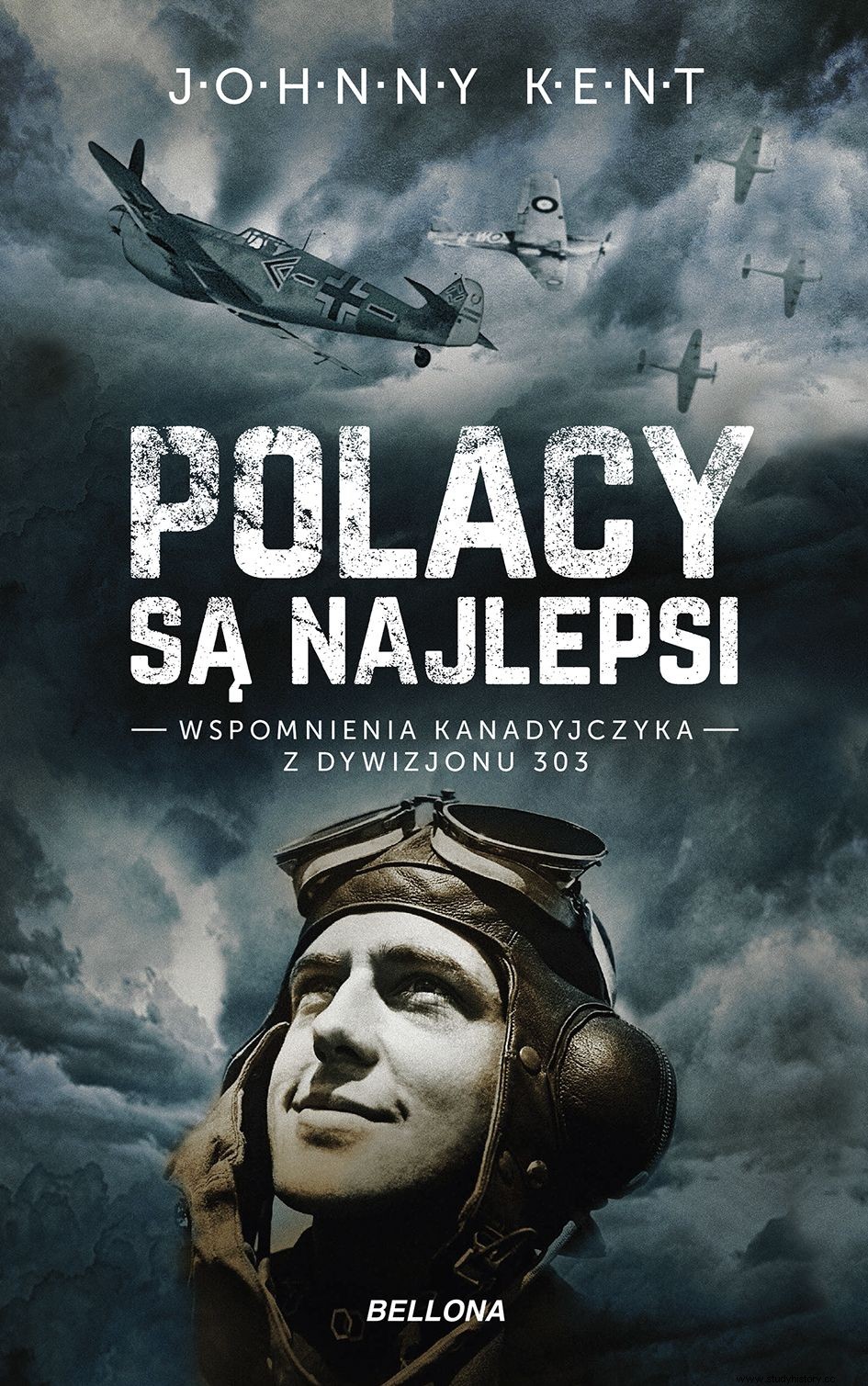

In January 1941, a journalist from the Sunday Times wrote about him: He was slim, with gentle features and delicate hands. His face was of little color, and only the strange ferocity of his pursed lips contradicted the thought that he might be a poet or an artist. […] His name is Major Kent, and in appearance he could be a poet - but I wouldn't like to be a German seeing those eyes and that mouth behind a rifle! John Kent was then 27 years old, a professional officer of the Royal Air Force (RAF), air ace, participant in the Battle of Britain and a former commander of one of the two squadrons included in the now famous 303 Squadron.

He came from Canada, where he became fascinated with aviation as a child, thanks to planes from a nearby flying club and the press euphoria after Charles Lindbergh's flight from New York to Paris. In 1933, he became the youngest in Canada to hold an aviation license. Shortly thereafter, he emigrated to Great Britain, where he joined the RAF fighter aviation.

As he himself mentioned in the book "Poles are the best" :

I read everything I could find about my aviation heroes such as Barker, Bishop, McLeod, Mannock and McCudden. Most probably - like many others - I was delighted with the stories of great hunting aces, but at that time it did not even occur to me that one day a convenient war would take place that would allow me to take part in similar fights.

For several years, the English made him understand that he came from the provinces, but he proved that he was a brave aviator, including very dangerous attempts to break through balloon barriers by plane.

The balloon dam over London during World War II.

The balloons were tied to the ground with steel cables, so the experiments ended with serious damage to the wings, and when a few hundred meters long rope got tangled in the plane once, the Canadian landed in the glow of the blue explosion that appeared behind his machine. He learned from pale mechanics that he had hooked the rope on a high-voltage cable, which had broken, but had previously caused a great and effective short circuit. He also tested other novel anti-aircraft weapons consisting of combinations of ropes, bombs, parachutes and rockets.

An adventurous road to a fighter squadron

After the outbreak of the war, he conducted aerial reconnaissance from high altitude, flying an unarmed Spitfir. During the French campaign, he competed on the school's Tiger Moth, racing against German bombs that fell into the abandoned airfield and then flew just above the treetops to avoid Nazi fighters.

At another base, while checking the damage of a British bomber, to the dismay of Kent and the others present, the bomb door suddenly opened and the payload was stuck in the ejectors. Not only that, just behind the fuel tank, a German incendiary projectile was discovered that was still smoldering.

After the defeat of France, the Canadian aviator went to Great Britain and waited for assignment to a fighter squadron. Eventually, he became the squadron commander in the Polish 303 Squadron, which was being formed. Athol Forbes was appointed commander of the second squadron, and Ronald Kellett was appointed the commander of the entire unit. The Canadian did not like this idea, to put it mildly. As he wrote in his memoirs, "Poles are the best" :

It was probably the last drop that made the cup of bitterness - after all my efforts to be assigned to the foreign squadron that hasn't even been created yet! I was really fed up with it all and was really upset. All I knew about Polish aviation was that it had survived the clash with the Luftwaffe for about three days, and I had no reason to suppose that when flying from England, they would show their better side.

Initially, neither of the commanders was satisfied, considering the assignment as ordinary exile. Arkady Fiedler wrote about the doubts of the British. It was hard for the islanders to grasp that the strangers who had not proved their worth were entrusted with defending the heart of the Empire - London. The British also treated each other without much confidence in each other - Commanding Kellett was a reserve officer, while his subordinate Kent and Forbes were career officers.

Commanders, Instructors, or Overseers?

Poles arrived soon after. They weren't happy either. The mere assignment of the British to the newly formed unit was assessed positively. A fighter ace Witold Urbanowicz considered it a good idea, definitely facilitating administrative matters. The problem, however, was the unclear division of powers.

One of the Polish officers complained that it is not known where the competence of the British ends and the Polish commanders begin, and what the actual role of the British is. Historian Adam Zamoyski pointed out that British majors and captains were supposed to be in command, but Poles saw little more in them than instructors who were too cocky.

Ground staff of 303 Squadron (public domain)

It was not easy for both nations in one unit. Not only because the Poles wanted to fight right away, and the British officers required that they first learn new equipment, radio, tactics and language. It was also necessary to master the production machines "Made in England". British planes differed quite a lot from those to which Polish pilots were used to. They had retractable landing gear, they had radio stations, but also a different arrangement of instruments in the cockpit and differences with continental solutions - for example, the throttle grip worked in the opposite way than in Polish or French machines, and even the parachute handle was on the other side. Failure to acquire this knowledge could be a real disaster.

There were difficulties in communication. It was possible to communicate with Polish subordinates, at least at the beginning, only in Polish, French or by sign language. Kellett and Forbes had no problem with French, but Kent was from Manitoba, not Québec, Canada, and knew no French. However, he found his own way to get along, which was appreciated by his subordinates, giving him the nickname "Kentski" or "Kentowski". As he wrote in his memoirs, "Poles are the best" :

I did it like this:I pulled one or two pilots out of the plane and, pointing at the plane, I was saying "airplane" slowly and clearly. They understood what was going on and replied, "airplane," which I wrote phonetically. Then I walked around the plane, giving the English names of the various parts, and responding with Polish equivalents. In this way, step by step, I developed the entire procedure in Polish. I had it all phonetically written on my notebook on my knee for use when giving commands in the air.

Poles are the best

The British were also not sure for a long time about the skills of our pilots, their morale, they thought that the pilots were afraid of fighting after the losers in Poland and France. Meanwhile, their subordinates were among the best in Poland and in the world, they had aviation and combat experience from two campaigns, air victories achieved on worse equipment than the opponent had.

In the photo, Witold Urbanowicz, Jan Zumbach, Mirosław Ferić, Zdzisław Henneberg with pinned British decorations after the awarding ceremony. (public domain)

They wanted revenge on the Germans for the invasion of September 1939, the destruction of the country, separation from their loved ones, and the death of relatives and friends. They were annoyed that the training took a long time and that their orders were given by haughty imperial officers, and they showed their dissatisfaction in many ways, including by sloppy dress - unbuttoned sweatshirts, unregulated shirts and shoes - which must have made Kent dissatisfied, who he himself insisted was a hot advocate of military discipline.

Fortunately, when 303 Squadron was finally put into action, the British quickly found out what great airmen they were under their command. The Poles, aware of the inexperience of their commanders, often took the initiative in combat and demonstrated their combat skills, which were full of spectacular successes, later celebrated with alcohol together with the Anglo-Saxons. At the same time, the stocks of Kent himself, who had a strong head, grew. Fighting together with the enemy created strong bonds. The sense of brotherhood and gratitude for Poles grew. As Ronald Kellett emphasized later:

The fact that the three English pilots who commanded this squadron and squadrons survived the battle [for Britain] is a great merit of the Polish pilots.

Kent himself owed his life to a Pole. Once, attacking a German bomber, he suddenly saw with horror that he had a Messerschmitt Bf-109 on his tail. In a moment before the German, the Polish Hurricane "fired like lightning", which chased away the danger. Kent knocked down a bomber and at the airport he thanked the one who helped him: You're welcome - replied Zdzisław Hennerberg modestly, then added:By the way, you were chased by not one Messerschmitt, but six.

Spitfire planes. The most famous Polish airmen during the Second World War flew them.

No wonder that when British officers left the Polish Squadron at the end of 1940, John Kent turned from an initial skeptic into a great friend of Polish pilots with whom he was yet to come into contact. In a press interview from 1942 he admitted: When it comes to fighters, Poles are the best , on his planes he later painted a personal emblem in the form of a Polish eagle against the background of a Canadian maple leaf, on his uniform he wore a Polish aviation stowaw over the wings of the RAF, and ordered the British officer, who did not get up when the orchestra played the Polish anthem, to stand at attention and blew his nose . He did it in defense of Polish honor like the real Janek Kentowski.

Literature:

- Bohdan Arct, Polish wings in the West, Warsaw 1970.

- Antoni Ares, 303 ups and downs. The adventurous fate of the heroes of the Battle of Britain, Warsaw 2016.

- Arkady Fiedler, Squadron 303, Poznań 1974.

- Robert Grethengier, Wojtek Matusiak, Poles in defense of Great Britain, Poznań 2007.

Jan Jokiel, Participation of Poles in the Battle of Britain, Warsaw 1972. - Johnny Kent, Poles are the best. Memoirs of a Canadian from 303 Squadron, Warsaw 2017.

- Wojciech Krajewski, Witold Urbanowicz - the legend of Polish wings, Warsaw 2008.

- Wacław Król, Polish aviation squadrons in Great Britain 1940-1945, Warsaw 1982.

- Lynne Olson and Stanley Cloud, A case of honor. 303 Kościuszko Squadron. Forgotten Heroes of World War II, Warsaw 2004.

- Witold Urbanowicz, Ace. Memories of the legendary commander of 303 Squadron, Znak Publishing House, Krakow, 2016.

- Adam Zamoyski, Forgotten squadrons. The fate of Polish airmen, London 1995.

- Jan Zumbach, The last fight. My Life as an aviator, smuggler and adventurer, Warsaw.

- Portal www.polishairforce.pl

Buy the book at a discount on empik.com: