You could have been saved from your Ottoman captivity by rich relatives or by a lucky accident. A few Poles, however, had a better idea - a daring escape! They kidnapped galleys, murdered torturers, disguised themselves as monks ... there are even reports of our compatriot who escaped in a balloon!

The most famous Pole who escaped the Ottomans is probably Marek Jakimowski. In 1620 he was taken prisoner of war at the Battle of Cecora and sold to galleys. In 1623 or 1627 he led a rebellion, took over the ship, lost the Turkish pursuit and happily reached Italy.

It turns out, however, that Jakimowski was not the only resident of the Commonwealth to say goodbye to slavery in the style of an adventurous novel. Here are some similar stories.

A rope in a flash

Hardly any Polish commander took the toll on the Turks as as Prince Samuel Korecki . He made sure that Moldova remained in the Polish sphere of influence. He placed the pro-Polish candidate Alexander Mohyla on the throne there, and for several months he resisted the Turks, who were dissatisfied with this turn of events.

In the end, however, in 1617 he was taken prisoner by the Ottomans. Although he disguised himself as a simple soldier, he was recognized anyway . He was taken to Constantinople.

The Sultan offered him freedom and a high position in the Ottoman army in exchange for his conversion to Islam . Korecki rejected the proposal. He was imprisoned in a fortress on the Bosporus. Perhaps in Rumeli Hisarı, where, according to legend, the unfaithful wives of the sultans, sewn in a leather sack filled with stones, were thrown from one of its towers.

Samuel Korecki - a brave soldier and adventurer (source:public domain)

Korecki decided to leave the prison in a different way. As he came from a wealthy family, under normal conditions the Turks would have received a ransom, and Prince Samuel waved them goodbye and returned to the Commonwealth. But the Muslims did not agree to give him back his freedom for money - it took its toll on them so much. In that case, he had to return it to himself.

A prisoner received various gifts from relatives and friends, which he shared with the guards. Especially when alcohol was shipped. Therefore, no objections were raised when one day a Greek, the envoy of the crown cup-bearer Mikołaj Sieniawski, appeared with a bottle of wine for Korecki. However, this time there was no noble drink in the bottle, but ... a rope and an iron ball.

When on the November night of 1618 the alcohol-overwhelmed guard was in the arms of Morpheus, prince Samuel Korecki sawed three iron bars, fell down the rope and ran to Constantinople . There he hid with a monk.

The Ottoman services searched for the Polish nobleman with great determination. Korecki was patient. He waited two months with his host, and then, pretending to be a merchant, he set off towards Italy, and from there to Poland .

Prince Samuel wanted revenge for his misfortune. Unfortunately, in 1620, at the Battle of Cecora, he was again captured by the Turks. This time he was watched more closely and made sure that he would never be released again. In 1622 he was murdered in prison.

Sabers in the stash

The nobleman Jan Wołkowski spent twelve years in the army until he was taken prisoner by the Tartars. Sold to Turkey, landed on a galley . He had some luck in the misfortune - he did not have to row, but served in the hold and was only shackled at night.

He underestimated the "kindness" of the torturers. On the contrary:he wanted to run away. He introduced a companion of misery, the Italian Bartolomea Trilla, into his plan. They found two sabers forgotten by the soldiers on board . A good starting point, however, they had to be patient and wait for the right moment.

It wasn't until a few months later that they could go into action. It was December 21, 1630. Their galley stood on the uninhabited part of the Anatolian coast, where the captain wanted to gather wood supplies.

Some Turks took several dozen slaves with them and went inland. There were sixty Muslims on board, twice as many wrapped galleys, plus a dozen wrapped up to load wood in the hold. It was an occasion!

Eight slaves, including Wołkowski and Trilla, armed with two sabers, clubs and cannonballs attacked the Turks. They managed to surprise the torturers and then throw their sabers to the chained galleymen.

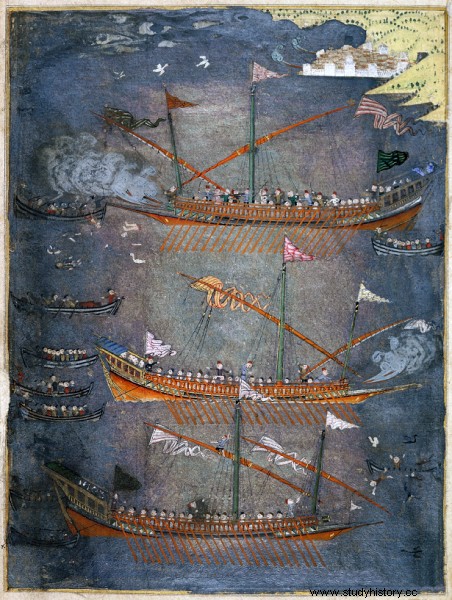

This is what Turkish galleys looked like in the 17th century

Screams were heard ashore. Half of the slaves cutting wood ran towards the galley. The rest froze, fearing that if the rebellion failed, they might be faced with, let's say delicately, unpleasantness, including impalement. And that lost them.

Most of the escapees happily reached the galley. The Muslims blocked the way for the undecided and murdered them . As the author of the report on the rebellion of Wołkowski put it, "Turks cutters" could not help "tree cutters". In addition, the wind had risen, so it was impossible to waste a moment. The anchor ropes were cut off and they were put out to sea. While it was the worst time to sail in the Mediterranean, there was no other option.

In January 1631, the rebels reached Malta, where they sold the gallery to the Knights of Malta. There the former slaves split up. The French, Italians, Spaniards, Croats and Greeks stayed on the island. Poles headed by Wołkowski continued their journey. In March 1631 they reached Rome and later returned to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Galley without oars

When Wołkowski and his companions greeted their families, a rebellion rose again at another Ottoman galley , and it was again headed by a Pole - a nobleman Bazyli Rohatynski. His story was quite typical. Taken captive by the Turks, he refused to convert to Islam, so he ended up on a galley, from which he wanted to escape as soon as possible. The idea was simple:murder the 128 Turkish crew while sleeping.

Rohatynski brought several slaves into the plot. It was known that as the action unfolded, the rest would join the rebellion. On the night of May 23-24, 1631, they began to act. The galley stood in the port of Chios, and the Turks slept at their best, drunk with alcohol .

Spanish galeas (large galley) included in the "Great Armada". The galeas crew could reach up to 700 men. The oars were very heavy, with up to 8 rowers for each (source:public domain).

The rebels, armed with four sabers, three cleavers, two spits and a few arquebuses, began their bloody work. They killed ninety-six Turks, took thirty-two prisoners and chained them. They were about to leave when they realized that… they had no oars.

These were usually deposited on land during the winter, from which the galley, standing at an anchor, was quite distant. It was May and the shipping season was just beginning in the Mediterranean Sea. The fact that the galley was "unarmed", that is, without oars, contributed to the lack of vigilance on the part of the Turks, who did not choke their slaves and forgot to post a guard when drunk - writes the historian Andrzej Dziubiński, discoverer of the account of the Rohatyński rebellion.

But since the galley took over, it was impossible to withdraw. Under the cover of night a lifeboat approached a warehouse ashore and the oars began to be lifted . Each of them weighed about one hundred and thirty kilograms, and it took fifty-two! When all of them had been removed from the warehouse and still not enough, a few were "borrowed" from an empty galley next door.

Fortunately, Rohatyński and the others managed to escape. After fourteen days they landed in Sicily . Later, only a quarantine ordered by the local viceroy, a thanksgiving procession to the Madonna in Trapani, a visit to Rome - and Rohatynski with his countrymen, who were present at the galley, could return to his homeland.

The Polish count is escaping in a balloon?

This story would have the potential of the most spectacular escape of a Pole from Turkish captivity. Unfortunately, the Polish accent is probably the result of a mistake, but it is also worth mentioning this event.

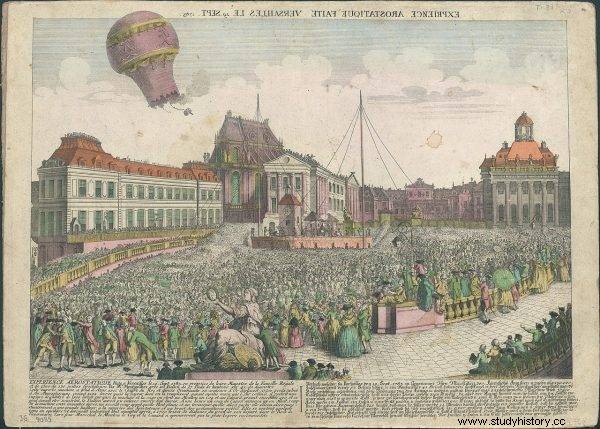

The Turkish historian Nejib Asym wrote that a certain Zambecari, a Polish count, serving in the Spanish fleet, was captured by the Turkish army and taken to Istanbul. In 1790 he escaped with a balloon he constructed , arousing admiration and fear among the locals. They had never seen a "great ball of fire" floating in the air in the Turkish capital before.

Graphics showing the flight of Montgolfier's balloon with a basket with animals, 19 September 1783.

This is obviously an apocryphal story - said Pierre Oberling, who studies the history of Turkish aeronautics. Francesco Zambeccari (for two "c") was actually Italian, he flew balloons, but he had nothing to do with Poland. More interesting is the fact that this story states that if someone spectacularly escapes from Turkish captivity, he was certainly Polish.

Will it work itself out?

Many slaves from the Commonwealth were not as lucky as the described Poles. Either their attempts to rebel were unsuccessful (which could mean death in agony) or they waited for a change of fate. After all, they could meet Trinitarians, dealing with the redemption of prisoners, or ... the prince.

In 1625, Prince Władysław (later Władysław IV), on a pilgrimage across Europe, stopped at the port of Livorno. By chance, a galley moored there - the Italians captured it from the Turks, but they did not return the galleys to freedom, treating them as "part of the inventory".

Among the unfortunates were the inhabitants of the borderlands of the Republic of Poland. As one of the diarists recalled: Among the prisoners who were in the galleys, were eight of our Russians and their freedom was granted at the request of the king [!] Of the gentleman.

Bibliography

- Czamańska Ilona, The Moldavian campaign of Samuel Korecki 1615-1616 , [in:] Si vis pacem, para bellum. Security and politics of Poland , edited by Robert Majzner, Częstochowa - Włocławek 2013.

- "Der Islam:Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kultur des islamischen Orients" 1928.

- Dziubiński Andrzej, Escapes of galleymen, Poles and Ruthenians, from Turkish captivity in the first half of the 17th century. , "Kwartalnik Historyczny" 106, 2009, issue 3.

- Gałczyńska-Kilańska Kira, Poles in the Land of the Crescent , Krakow 1974.

- Knopek Jacek, Activity of Polish knights, pilgrims and travelers in North Africa until the beginning of the 20th century , "Przegląd Orientalistyczny", 2000, No. 3-4.

- Niesiecki Kasper, Polish Herbarz , pub. Jan Nepomucen Bobrowicz, vol. 5, Leipzig 1840.

- Oberling Pierre, A History of Turkish Aviation:Aerostation among the Ottomans , "Archivum Ottomanicum", vol. 9, 1984.

- Sajkowski Alojzy, Italian adventures of Poles. XVI – XVIII centuries , Warsaw 1973.

- Szczerbicka-Ślęk Ludwika, Old Polish pride. From the history of melic poetry , Wrocław 1964.