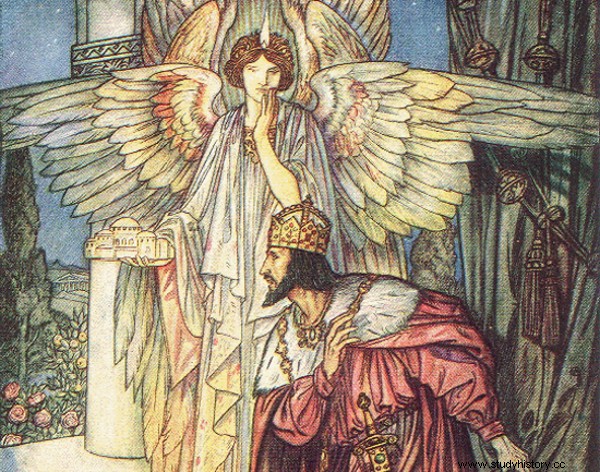

His character fascinates to this day. In forty years, he brought Byzantium to the height of its power. Of all the rulers of the Eastern Empire, he was the one who had the best chance of rebuilding the Roman Empire. How close did he get to that goal, and why did he ultimately fail?

Emperor Justinian I the Great, who ruled in the Eastern Roman Empire in the years 527-565, reformed the administration, law and army, and did not shy away from engaging in religious issues. He made a huge contribution to the development of construction and infrastructure of the Byzantine Empire. During his lifetime and on his initiative, the famous Hagia Sophia was created. But he wanted even more: his main goal was to rebuild the might of the Roman Empire within its borders from the 4th and 5th centuries .

Law first

For Justinian, one of the basic symbols of the power of the Roman state was law. No wonder that he himself wanted to create a new, up-to-date and consistent codification. He entrusted this task to Trybonian, the greatest lawyer of his time. Barely a year after his accession to the throne, he established the first of the commissions constructed by his assistant. Its aim was to compile the first uniform and complete set of imperial regulations since the time of Hadrian.

We didn't have to wait long for the results of the team's work. On April 7, 529, Justinian was able to announce a set of ordinances under the leadership of Trybonian - Codex , later renamed Codex vetus . Then, on December 15, 530, the commission, expanded by several prominent law scholars from schools in Constantinople and Beirut, began researching and selecting material contained in the writings of the most eminent Roman lawyers. Although the emperor gave her ten years to do so, he prepared a collection - the so-called Digesta - it could be announced on December 16, 533. Earlier in November, Justinian also published an official textbook for the study of law called Institutions ( Institutiones ). ).

In the same year, the emperor also reformed the law studies themselves. Constitution Omnem he allowed law education only in Rome, Constantinople and Beirut. He also extended the duration of studies to five years and specified the program of each semester. By the way, he left us a lot of information about the studies and students of the 6th century. For example, he strictly forbade all student "games" that are unworthy, hideous and "cause only harm." This indicates the existence of the problem of the so-called "student wave" in Byzantium .

Justinian ordered the first codification of the law since Emperor Hadrian.

The codification was completed on November 16, 534, Codex repetitae praelectionis, in other words ... new Codex release from 529. The latter had to be updated and, above all, agreed with Digest . As summed up by Professor Aleksander Krawczuk in the "Post Office of Byzantine Emperors":

All three works - the Code, Digest, Institutions, and later edicts of Justinian, the so-called novels - are commonly referred to as Corpus iuris civilis, i.e. ". It is the sum of the legal wisdom of ancient Rome and at the same time underpins the legislation and legal thinking in almost all European countries, indirectly operating until today .

Wars on multiple fronts. Persians

"In the 6th century, the Byzantine world was dominated by three great regions" - points out John Haldon in his book "Byzantine Wars" . These were, as he writes, "The Balkans, sometimes reaching north as far as the Danube, Asia Minor (Anatolia, roughly the area of today's Turkey), and the Middle East of Syria, Western Iraq and Jordan ". The researcher also supplements them with Egypt, North Africa, Italy and the seas connecting these lands. In most of these areas, Justinian waged hostilities.

The war with Persia began after the twenty-year peace period, a year before Justinian took over independent rule. Initially, his enemies led the offensive action, but the situation changed when Belisarius became commander-in-chief in the east in April 529. His army, strengthened by reinforcements, moved to the vicinity of Dara. At the same time, peace negotiations were conducted.

However, the talks did not work, so in the end the Persians decided to strike. In the summer of 530, they set off for Dara. From the moment of its creation, this fortress was a salt in the eye of the Sassanid ruler. Belisarius had a force twice as small as the enemy - 25,000 against some 50,000 of the enemy's troops. Despite this, he decided to fight a defensive battle that brought the Romans success. According to Procopius, about 8,000 Persians were killed in fierce combat and a short chase.

The success of the Roman army was undoubtedly determined by the good tactics adopted by Belisarius and his ability to react quickly to changes in the situation on the battlefield. It must be emphasized that the Byzantine commander was very careful. Before the battle, he carefully prepared the battlefield and wisely placed his forces there. As a result, as John Haldon writes in his book "The Byzantine Wars" :

(...) the Battle of Dara was an important point in the long war on the eastern front, as for the first time in years, Roman forces - and even weaker numbers - managed to defeat Persians in the open field. This affected the morale of both Romans and Persians.

The victory at Dara coincided with the Roman success in the Battle of Satala, fought at the Armenian theater of war. However, the following year, the Persians managed to defeat Belisarius in a bloody clash at Callinicum on the Euphrates. The unfortunate commander was found guilty of this defeat - as a specially appointed commission ruled - and recalled from the east. The Sassanids tried to keep the offensive that same year, but the death of their ruler Kawades on September 13, 531 and the reign of Chosroes I ended the hostilities.

One of the lasting remains of Justinian is the Hagia Sophia temple.

Peace negotiations, started in the spring of 532, eventually resulted in a difficult compromise. It was agreed that the empire would bear the cost of maintaining fortresses in the Caucasus region. Justinian also undertook to move the military headquarters from Dara further west to Constantine. In return, the Persians withdrew from Lazyka, keeping Caucasian Iberia in their hands.

This room, dubbed "perpetual", lasted less than eight years. After this period, Chosroes attacked Syria, taking advantage of Byzantium's involvement in Europe. The war that began then lasted almost twenty years. Its most famous episode was the fierce siege of Edessa, which ended with the withdrawal of the Persians from the city walls for ransom. In the end, both countries, exhausted from struggles on many fronts, made peace in 561. As summarized in the treatise, Aleksander Krawczuk:

The Persians eventually gave up the Lazov land, mostly Christians, and the emperor was to pay the king 30,000 gold a year, some in advance in seven years. The border in Syria and Mesopotamia remained unchanged, and both sides undertook not to build new fortifications and fortresses. Localities where merchants from both countries could trade were designated. The fugitives were to be handed over to each other. Christians in Persia could profess their faith, but were not allowed to carry out any missionary activity .

Africa and the Vandals

After making a "perpetual" peace with Persia and suppressing an extremely bloody popular uprising, the so-called "Nik uprising", Justinian became interested in Africa, dominated around the middle of the 5th century by the Vandals. He began preparations for the reconquest of the provinces there. In June 533, the army, embarked in more than five hundred ships, left Constantinople. Belisarius was in command.

Belisarius led many campaigns - in the Balkans, in Africa and in Italy.

The Empire's conquest had been surprisingly easy. After the battles of Decimum on September 13, 533 and Tricamarum (around December 15, 533) and the capture of Carthage and Hippo, the Vandal state ceased to exist. Their king Gelimer took refuge in the mountains of Numidia. He finally surrendered in March 534. There was no harm to him - he received considerable goods in Galatia. If he had only agreed to convert from Arianism to Catholicism, as the Orthodox Justinian strongly urged him to do, he would certainly have received Roman honorary titles as well.

The Byzantine Empire regained Africa as far as Ceuta, but also Corsica, Sardinia and the Balearic Islands. In the summer of 534, Belisarius returned to Constantinople. There he was allowed an extraordinary honor - a triumphant entry into the city. This honor has not been met by any of the chiefs (other than the emperors) since the times of Octavian Augustus!

It was then that the imperial insignia, looted by the Vandals during the invasion of Rome in 455, were brought to the capital along with the spoils and prisoners. No wonder that on January 1, 535, Belisarius took over as a consulate as a reward for his achievements. Soon Justinian also decided to entrust him with another task - a reflection for the Empire of Italy.

Pyrrhic victory in Italy

The emperor, taking advantage of the internal problems of the Ostrogoths ruling Italy, ordered in June 535 to start a new campaign on two fronts simultaneously - in Dalmatia and in Sicily. The former passed from hand to hand, but Belisarius took the latter relatively easily. Having sailed from there to Italy, he took Rhegium (Reggio di Calabria), and Neapolis (Naples), and in December 536 entered Rome .

For a moment it seemed that the recovery of Italy would be as easy for the Byzantines as it was to deal with the Vandals. Nothing could be more wrong. The new ruler of the Ostrogoths - Witiges - took decisive steps and in February 537 besieged the Eternal City. The fighting was fierce and devastating, but the Byzantines persisted. In March 538, Witiges returned north.

In May 540, the victorious Belisarius entered the enemy capital, Ravenna. Witiges met a fate similar to Gelimer - he received earthly goods and then the title of patrician. However, this did not mean the end of the war. The Ostrogoths withdrew to the north, and in the fall of 541 they proclaimed an extremely talented warrior - Totila - their king. The latter immediately started regaining Italy.

The so-called Second Gothic War broke out, which had dire consequences for the state of the imperial treasury, and above all for the lands on which it was fought . In the summer of 544, Belisarius returned to Italy, but this time with no success. It marked the end of his great career. In his defense, it should be added that he was entrusted with extremely thin forces, preventing an effective offensive. This was due to the resumption of the war with the Persians; It was also not without significance that in 542 the population of Byzantium was decimated by the epidemic of "Justinian's plague".

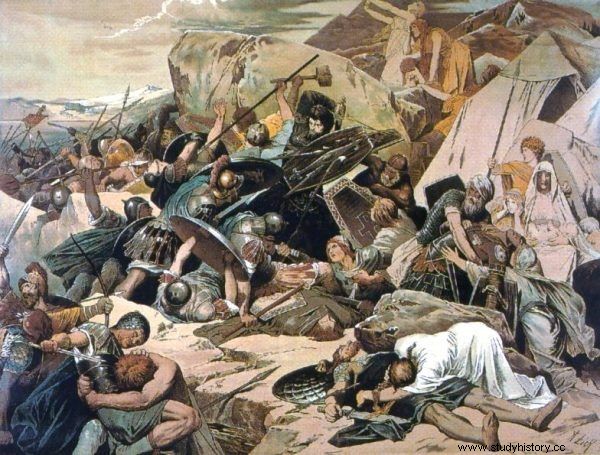

Rome was again changing hands, and the outstanding commander was recalled to the capital. It was not until the spring of 552 that another army set off on Italy, this time by land. Narses, who stood at its head, defeated the Ostrogoths in the bloody battle of Busta Gallorum at the end of June. Death in battle reached King Totila himself.

The Byzantines defeated the Ostrogoths at Lactarius.

The leader of the expedition regained Rome, then defeated the deceased ruler's heir, Teja, in the Battle of Mount Lactarius. By the end of 562, the Ostrogoths had lost their last points of resistance, such as Verona and Brescia. All Italy, up to the Alps, terribly devastated by the war lasting more than twenty years, fell under the rule of Byzantium. Ravenna became the actual capital of the recovered territories. Meanwhile, the empire's army also regained significant areas of southern Spain, including the cities of Malaga, Cordoba and Cartagena.

Emperor Justinian died on November 14, 565. His reign was one of the greatest periods in the history of Byzantium. "It ended a great epoch in the history of mankind, and not - as he wished - the beginning of a new era," said the well-known Byzantineologist Georg Ostrogorski. Justinian wanted to give a "new life" to the old Roman Empire - to rebuild it within the borders of the times of its greatest power. Despite great successes, it was a task beyond his abilities

Selected studies:

- R. Browning, Justinian and Teodora, PIW 1996.

- J.A. Evans, Justinian and the Byzantine Empire , Bellona 2008.

- T. E. Gregory, History of the Byzantine Empire , WUJ 2008.

- J. Haldon J, Byzantium. Outline of history , Libridis 2006.

- J. Haldon, The Byzantine Wars. Strategy, tactics, campaigns , Rebis 2019.

- J. Herrin, Byzantium , Rebis 2009.

- I. Hughes, Belisarius. Chief of Byzantium , Poznań Publishing House 2016.

- A. Krawczuk, Byzantine emperors , Iskry 1996.

- C. Mango, History of Byzantium , Marabut 2004.

- The world of Byzantium. Volume I:Eastern Roman Empire 330-641 , ed. C. Morrison, WAM 2007.

- G. Ostrogorski, The History of Byzantium , PWN, 2008.

- P. Sadowski, Law school in Roman and Byzantine Beirut , Publishing House of the University of Opole 2019.

- J. Shepard, Byzantium around 500-1024 , Dialog 2012.

- J. Wolski, Universal History. Antiquity , PWN 2012.

- A. Ziółkowski, History of Rome , PTPN 2005.