On March 1, 1881, Russia was shocked by the news of the death of Alexander II. In the heart of St. Petersburg, on the Catherine Canal, a Pole, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, a member of the terrorist organization Wola Ludu, threw a bomb at the monarch.

This was the seventh attempt to destroy the emperor, who went down in history as a great reformer. (...) There was greater freedom of expression in the country, which caused some youth to deny the existence of the monarchy.

Destruction

Writers also influenced Russian society. In his 1862 novel Fathers and Children, Ivan Turgenev popularized nihilism:the destruction of existing social institutions through the complete denial of power, religious and moral values. Taking root among educated Russians, nihilism turned into a radical, destructive force operating according to the principle:"The lust for destruction is a creative drive."

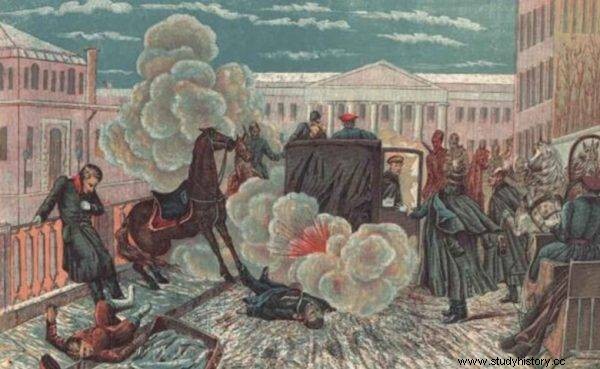

Explosion of a bomb thrown by Ignacy Hryniewiecki

In the 1860s and 1870s, many revolutionaries left the countryside in the belief that the peasants would immediately absorb their views. . But the villagers did not understand these ideas and often turned in police agitators.

Disappointed with the mediocre results of their actions, radical youth went a step further and founded the Will of the People (Narodnaya Wola) organization that sanctified violence and terror as a political tool and rejected persuasion and enlightenment as ineffective methods of struggle. (...) Wola Ludu included murder in its repertoire, and the main target of the attackers was Alexander II.

Ignacy Hryniewiecki went down in history as the first Polish terrorist.

According to radical reasoning, it was easier to kill the Tsar than to overthrow the system. The death of the ruler was to force reforms on his successors or encourage the people to continue fighting with the existing political system.

Up to seven times a piece

One of the attacks on the emperor's life was organized on April 2, 1879, right next to the Winter Palace. (...) Another attempt to kill the Tsar was made after a few months, by planting a bomb under the railroad tracks on the route that Alexander II was to return from Crimea (...).

After these failures, Stepan Khałturin, a member of Wola Ludu, took the matter into his own hands, who took a job as a carpenter at the Winter Palace and stocked up dynamite there to blow up Alexander II and his family in their own residence. The attack was scheduled for February 5, 1880, and the explosion was to take place at 7.00 p.m. during dinner. But the emperor was late for his meal, so the explosion happened while the dining room was empty.

After a few months, the Wola Ludu organization made its sixth attempt to murder the tsar, who had once again escaped alive. The terrorists were not discouraged by the failures and decided to make an attempt on the streets of St. Petersburg during the monarch's ride.

The venture was headed by Andrei Zelabov, who decided that in order to implement the plan, you should carefully read the ruler's schedule and the route of his travels. This is how the observation group was created, headed by Sofia Pierowska. It included Ignacy Hryniewiecki.

The text is an excerpt from Violetta Wiernicka's book "Poles who amazed Russia", which has just been released by the Bellona publishing house.

The first Polish terrorist

The family of this nobleman born in the Minsk governorate (now the Bobruisk region in Belarus) led the life of simple farmers. (...) They had nine children, it was not easy for parents to keep such a group. Despite the difficult financial situation, the Hryniewiecki family took care of Ignacy's education, first sending him to a primary school in Bielsko, and then to a middle school, i.e. a secondary school, in Białystok (...).

In Białystok, Ignacy became acquainted with the views of the "Narodniks". It is not known why their ideology seemed so attractive to him:was it about a youthful search for justice or a sense of self-harm?

After graduating from high school, Hryniewiecki enrolled at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of the Technological Institute in St. Petersburg, where took part in a one-day strike, for which he and other participants of the event were expelled from the university. But after a few weeks, the Pole and his companions were forgiven for this prank and re-admitted to the university.

The removal from the list of students did not discourage Ignacy from becoming more active in anti-state activities:collecting money for the organization, agitation among students of the Institute of Technology and Warsaw workers, maintaining contacts with activists from other cities (...).

In mid-1878, Hryniewiecki faced further problems:he was deprived of a scholarship for participating in an anti-government student rally. which helped him to stay in St. Petersburg, and was left for a second year. The punishment did not dampen the enthusiasm of the young man who, in the spring of 1879, set off to the countryside to establish revolutionary centers there.

However, as already mentioned, the simple Russian peasants could not understand the propagated content, so the initiative was unsuccessful. For this reason, Hryniewiecki rejected the evolutionary nature of the reforms and concluded that the only method of fighting the existing order was terrorist activity, which he decided to devote his life to. Soon he became a member of Wola Ludu (…).

Plot of the assassination

In Wola Ludu, Hryniewiecki founded workers' circles, was a typesetter in the organization's illegal typographic workshop, and was also involved in the distribution of forbidden literature. All this consumed more and more time for Ignacy, which caused him to neglect his studies and in June 1880 he was removed from the list of students. (...) From then on, nothing prevented him from devoting himself entirely to the fight against the tsarist regime (...).

The assassination of the Tsar has been carefully planned.

Ignacy joined the six-person group following the everyday life of the emperor. (...) Soon, based on the results of the observations, a plan of the assassination was developed. It was scheduled to take place on Sunday, as Alexander II traveled to Manezh Mikhailovsky to host the parade and then traveled home to the Winter Palace.

The emperor's return path led through Sadowa Street or the Catherine's embankment (the monarch followed the latter route when he visited his cousin Catherine, who lived on the banks of the Neva). In the first case, during the passage of the imperial carriage, a huge missile was supposed to explode, installed in the trench at the cheese shop on Sadowa Street.

If the explosion had not happened, the work would have been completed by the bomb throwers, who would have stepped into action also in the event that the tsar had followed the Catherine's Wharf. Andrei Żelabov included a Pole in the group of pitchers (...).

"Alexander II must die"

The coup was scheduled for March 1, 1881, but the day before the group's leader, Zelabov, was arrested. The action seemed to be postponed. Unexpectedly, Sofia Pierowska, Żelabowa's girlfriend, took on the management of the project.

On the night of February 28 to March 1, Hryniewiecki wrote a manifesto for posterity:“Alexander II must die. His days are numbered. […] He will die, and so will we, his enemies, his killers. History proves that the great tree of liberty demands victims. [….] Fate condemned me to an early death, so I will not witness victories, I will not survive a single day or an hour in a bright time of triumph. […] ”.

Alexander II went to Manezh Mikhailovsky, assisted by the Cossacks and the policemen of the city of St. Petersburg. After accepting the parade at 1:00 p.m., he began his journey home. He was walking along the Catherine Canal to visit his cousin who lived there. (...) The pitchers, including Ignacy Hryniewiecki, took their positions.

Then the emperor finished drinking the last tea in his life and at 2:10 p.m. he said goodbye to the hostess. When five minutes later the tsarist carriage passed Nikolai Rysakov's pitcher, the latter threw a bomb, but the charge exploded in the back of the carriage and Alexander II emerged from the attack unscathed. The terrorist was immediately captured.

Members of the entourage asked the ruler to leave the crime scene quickly, but the tsar wanted to make sure that the wounded - accidental victims of the attack - would receive medical attention. This delay cost Alexander II his life.

"Man died on March 1"

Hryniewiecki, standing on the bridge, approached the ruler and threw a bomb at his feet. "The explosion was so strong - reported the witness - that on the gas lamp all the lenses disappeared, and the lamp post itself was bent." Twenty people were injured, including the emperor, whose feet were shed with streams of blood (...).

"The tsar looked monstrous," recalled Grand Duke Alexander, the dying cousin. - His right leg was torn off, the left one was shattered, countless wounds covered his head and face. One eye was closed, the other was completely expressionless ”(…).

The attack carried out by Hryniewiecki was the seventh terrorist attack directed against Alexander II. And the first effective one.

The doctors doubled and troubled, but their efforts turned out to be in vain - at 15.35 the ruler died. According to the tradition not to use the word "death", Vladimir, the second son of Alexander II, opened the window wide and announced to the people taken in the square:"His Imperial Majesty orders you to live long". (This is a Russian euphemism about someone's departure.)

(...) Hryniewiecki also suffered serious injuries, including:hemorrhagic wounds on the head and face, 19 wounds 1 to 2.5 cm in diameter on the right shin, a 7 cm wide wound in the rear part of the right foot, crushed bones of the right foot shaving, left eye haemorrhage, no light reaction in right eye. The Pole was breathing with difficulty, his pulse was imperceptible. So he was taken to the hospital, where he woke up around 9 p.m. Doctors asked the patient for the name, but he replied, "I don't know," and then he died.

The pitcher Rysakov, captured on the same day, sang everything to the investigators and the authorities quickly arrested the participants of the attack. For unknown reasons, the traitor did not mention the Pole's name, so he was listed in the case files as "the man who died on March 1". His identity was established only during the trial of the Wola Ludu members, which took place on March 30, 1881. The bombers were sentenced to death, on April 3 they were hanged in Siemionowski Square in St. Petersburg (...).

The authorities did everything possible to erase the memory of the attackers from the consciousness of the society. It was only after the Bolshevik coup in 1917 that the achievements of revolutionaries, including Ignacy Hryniewiecki, who was named after one of the bridges in Leningrad, were recalled. Only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the name of the bridge was changed to Nowo-Koniuszenny.

Source:

The text is an excerpt from the latest book by Violetta Wiernicka "Poles who amazed Russia", which has just been published by the Bellona publishing house.