Nowadays, many people suffer from the fact that after death, organs can be removed from the deceased for transplantation. Until quite recently, people had no doubts. As soon as they believed that the specifics from the corpse would help them, they were ready to take it in all sorts of forms. They were not even bothered by cannibalism ...

Do you think that desecrating human corpses by using them in truly cannibalistic medical practices is a relic of barbaric times? Nothing could be more wrong.

In Europe, remedies made of corpses were valued until the late 19th century, and in other parts of the world, such as Africa, they are used to this day. As early as the Middle Ages, it was commonly believed that powdered ancient corpse was considered a powerful, albeit rare and expensive ingredient in drugs.

The so-called mummy powder was made not only from the dead embalmed in the times of the pharaohs, but also from travelers who had the misfortune to get lost in the desert, where the burning sun naturally dried them to a chip. It is worth emphasizing that the then specialists called "mummies" not only the corpse subjected to the mummification process, but also just any parts of the body of a dead person. As Eleanor Herman writes in the book "Poison, or how to get rid of enemies in a royal way" :

Doctors believed that some vital energy remained in the body after death, especially in the case of executions or accidents when the life of a young and healthy person was suddenly interrupted. Vitality not used by the prematurely deceased person could be given to the person consuming his limbs.

The drug is authorized for use

The medics took it very seriously that, according to Jean La Fontaine, in 1618 the English College of Physicians included mummies and human blood in its pharmacopoeia. Why is it so significant? The Pharmacopoeia, or the so-called Pharmacy Code, is an official list of drugs authorized for use, which formerly also contained information on the methods of obtaining specific ingredients.

No mummy was safe (photo:Jay Malone, CC BY 2.0 license)

Due to their high price, medicines made from the human body were available primarily to representatives of the highest social classes. Crowned heads did not shy away from them, although they were far from enthusiastic about taking such medicines. Among these "cannibals for health" was probably the English Queen Elizabeth I of the 16th century. It is true that there is no direct reference to this in the sources, but her court doctors recommended remedies from the corpses to their other patients as effective remedies for various ailments.

It is certain that the cannibal was Elizabeth's successor, James I of Stuart. When the ruler became ill in 1616, his court doctor ordered him a specific, the main ingredient of which was a powdered, unburied human skull mixed with white wine. You should have drunk it at the full moon. As emphasized by Eleanor Herman in his book "Poison, or how to get rid of enemies in a royal way" , James I hated eating human flesh, and because of this disgust, medics wondered whether to replace the skull of a homo sapiens with that of an ox. In the book, Herman writes:

When treating epilepsy, doctors made medications from dried human hearts or a mixture of wine, lily, lavender and the entire human brain, which weighed about one and a half kilograms. Human fat has been used to treat tuberculosis, rheumatism, and gout. Doctors advised those suffering from hemorrhoids to stroke the deceased's hand with the severed hand - an extremely unpleasant picture when you recall it in front of your eyes.

Some recipes were terrifyingly detailed and macabre at the same time. At the beginning of the 17th century, a German doctor gave instructions on what to do to get a cure for the plague. A willing medic or apothecary had to search for… the body of a red-haired man that was not mutilated and had no blemishes. Moreover, the corpse had to come out of this world at the age of 24 by hanging, breaking with a wheel, or stabbing.

When we managed to locate such a rarity, the weather was still important; for the corpse was to lie in the open air for one day and one night. After such preparations, one could start preparing a cure for the plague. For which you needed a sharp knife and precision. The body had to be cut into thin strips, then sprinkled with myrrh and aloe powder and macerated in wine. Later, they were air-dried, so that, as Herman points out, they were supposed to look like smoked meat, and then they were ready.

From today's perspective, these practices seem disgusting, even barbaric. One would like to ask, how can one break the taboo of human corpses to stroke hemorrhoids? Richard Sugg has a simple answer to that. At the time of the popularity of mummy powders and other specifics of this autorament, mummies were the subject. In medical treatises of the time, they were treated in the same terms as cheese or milk, and were just as impersonal.

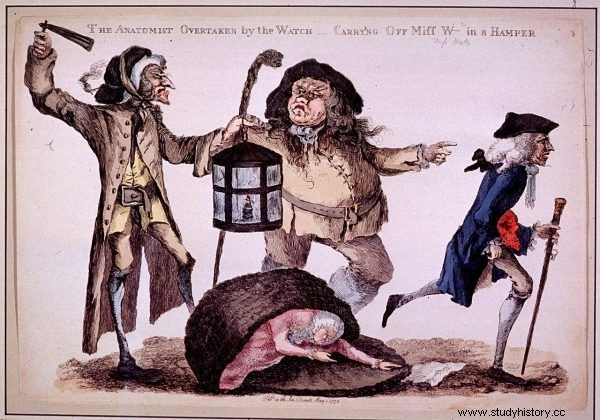

A caricature from 1773 showing the guards who found the body thief (photo:public domain)

It would seem that we have gone a long way in ethical matters since then, and we can look at the doctors prescribing powdered corpses from a moral pedestal. However, it is worth considering whether history has come full circle by accident. Modern cosmetic procedures, such as vampire facelifts, injecting platelet-rich plasma or implanting adipose tissue in certain parts of the body in order to increase it, sound surprisingly similar to old therapies using human bodies ...

Information sources:

- Herman E., Poison, or how to get rid of enemies royally , Horizon 2019 sign.

- Sugg R., Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires:The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians , Routledge 2016.

- Sugg R. The Smoke of the Soul. Medicine, Physiology and Religion in Early Modern England , Palgrave Macmillan 2013.