They dreamed that the world would lie at their feet. And they did not stop at nothing to achieve the intended goal. If they were alive today, they would be accused of genocide like nothing. Who exactly are we talking about?

Let's be honest:killing relatives was standard in this era. It was done by variously judged monarchs, such as the biblical Solomon (fratricide), king Herod the Great (three-time slayers), Emperor Nero (he killed his wife, brother-in-law and mother) or Constantine the Great, the first Christian ruler of Rome (a synocide and a spouse-killer).

In the case of the family, however, the circle of potential victims was at least limited. Worse, such an ancient ruler had ambitions to conquer new cities and lands. Then he carried death like Hitler or Stalin ...

Alexander the Great

This was the case with Alexander the Great. This most famous student of the philosopher Aristotle is called the greatest leader of antiquity. He dreamed of conquering the whole world. And, as was often the case in the ancient world, he began by dealing with his immediate family. There are strong suspicions that he was involved in the plot to kill his father, King Philip II. And even if he was innocent in this case, there is no doubt that he ordered the murder of his half-brother Karanos. The poor boy was reportedly thrown into a hot stove .

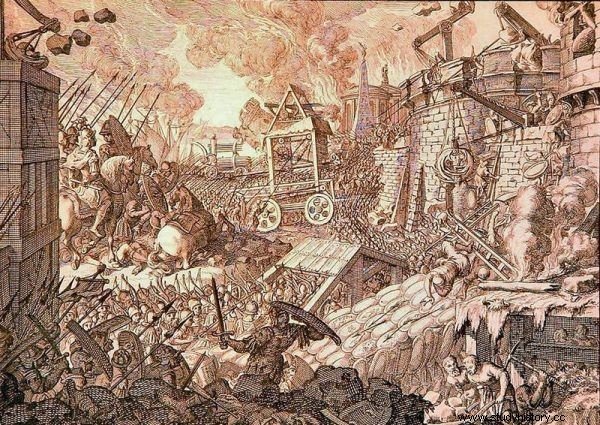

Alexander made an example of Tire for all those who thought about facing it (source:public domain).

The gains of the most famous Macedonian ruler were bought with the blood of thousands of people. An example would be the trial with the people of Tire. In 332 BC, an army led by Alexander the Great was stuck in its triumphal march outside this Phoenician city. The ambitious young king wanted to get them, It was only possible after a siege of several months. When his troops finally entered Tire, they had no mercy. This is what Peter Green, Alexander's biographer, wrote about this episode:

After crushing the last remaining resistance, Alexander's old soldiers roamed the city without any brakes, like bloodthirsty beasts hunting people. Hysterical, half mad after the long hardships of a terrible siege, were now only butchers, beating, trampling, tearing their victims apart until all of Tire turned into bloody, smelly butchery .

Some citizens locked themselves in their homes and committed suicide. Alexander commanded everyone to be killed except those who would seek asylum in the temples; his order was carried out with cruel satisfaction. The air was thick with smoke from burning houses. 7,000 Tyrians died in this monstrous orgy of destruction .

The fate of those who survived the slaughter was no better. The Macedonian ruler ordered two thousand men fit for military service to be crucified! The remaining 30,000 inhabitants of Tire were sold into slavery.

Another city in the way of Alexander the Great's army was Gaza. The Macedonian King besieged the city for two months. He discharged his rage, caused by another stoppage and wound (he was hit in the leg by a stone artillery shell), on the inhabitants. After the city was conquered, 10,000 men were slaughtered and women and children were sold into slavery . Batis, the brave commander of Gaza, was tied to a cart by the legs of the Macedonian king and dragged around the walls until he gave up his ghost.

Frank Fabian, a German historian, author of the book "The Greatest Lies in History", does not spare bitter words to Alexander:

It is impossible to describe all the massacres and slaughters he has committed. War has its cruel laws, but it exceeded all imaginable limits. He left poverty, disability and death behind him. And war was never enough. After winning one battle, he prepared the next. Having slaughtered 10,000 enemies, he wanted to behead (and beheaded) 20,000.

Fed up with ambition, Alexander was constantly striving for new, bloody conquests. The illustration shows a painting by Jean Simon Berthélemy showing a Macedonian ruler cutting the Gordian knot (source:public domain).

Alexander the Great's ideas also cost, often unnecessarily, the lives of his soldiers. And it wasn't about dying in combat. Returning from India in 325 BC, he led his army through a desert land called Gedrosia (today's southern Pakistan and Iran). For the Macedonian king's warriors, it was a road through hell. As reported by Peter Green:

They had a severe shortage of water and often had to walk 25 to 75 miles, mostly at night, from one pool of brackish water to the next. And when they finally reached their destination, people, maddened with thirst, plunged into a puddle, in armor and with all their gear, without hesitation. Many died from excessive drinking after dehydration, and many others suffered from sunburn.

The march cost the lives of tens of thousands of people. According to one of Alexander's 85,000 soldiers, no more than 25,000 survived . Others estimate that the initial state of the army is 60,000 and the final result is 15,000.

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar, a genius Roman leader, and in his spare time - the writer and lover of Cleopatra, has a slaughter on his conscience that can be undoubtedly described as genocide.

Even by ancient standards, Julius Caesar displayed unprecedented brutality. Pictured is a statue of Caesar in Romini (photo:Georges Jansoone; license CC BY-SA 4.0).

It was 55 BC. The river Rhine separated the spheres of Roman and Germanic influence. However, the Germanic tribes of the Usipets and Tensers, pressured by their neighbors, were forced to cross it. Gaius Julius Caesar reacted immediately. He drew 8 legions and Gallic auxiliaries - in other words, he raised an army of 50,000.

The Uzypetów and the Tenkter asked the Romans for time. They intended to return across the Rhine, but first they wanted to come to an understanding with their people about the land they could farm. Julius Caesar received the deputies of the Usipets and Tenkters and officially agreed to their proposals. And secretly ... ordered the murder of two Germanic tribes . It wasn't a fight, it was a slaughter. It is enough to look at Caesar's "Gallic War", where the chief boasts of his victory:

Here in the camp, those who managed to take up arms faster resisted us for a while and fought among the carts and luggage; while the remaining mass of children and women (for they had left the country with all their families and crossed the Rhine) began to flee in all directions; Caesar sent his cavalry to pursue them.

This is how representatives of the Germanic tribes were imagined in the 19th century. It has little to do with reality (source:public domain).

When the Germans heard the noise in the rear and saw their being murdered, they dropped their weapons, abandoned their battle signs and broke out of the camp, and when, after reaching the catchment area of the Meuse and the Rhine, they gave up hope of further escape, a great number of them were killed, and the rest fled into the river and died there as a result of terror, exhaustion, and the gusts of current. Our people, every one of them, except for a few wounded, returned to the camp safe after the war, which caused such fear, because the number of enemies was 430,000 people .

The number of murdered men, women, old people and children was probably overstated. And so it was about the lives of thousands of people. This crime of genocide was particularly disgusting because it was combined with treason and violation of parliamentary rights - Aleksander Krawczuk assessed in Caesar's biography. In 2015, the remains of some of the victims of that massacre were found in the Dutch town of Kessel.

Meanwhile, in the Roman Senate, almost everyone crowed with delight at the bravery of Julius Caesar. Only one, Cato the Younger, thundered at the faithless leader. He demanded that he be handed over to the Usipets and Tenkter - the few who managed to survive ...

The massacre of the two Germanic tribes was not a one-time jump. A sea of blood was spilled in Caesar's partitioning wars. For example, in the Gaulish Avarikum, he organized a massacre of city defenders. Of the 40,000 people, only 800 survived.

It was only in 51 BC, when the Roman leader was conquering the last stronghold of the Gauls, a settlement called Uksellodunum, that he showed a peculiar gentleness. He spared all the defenders their lives… but ordered them to cut their hands . If the comic book heroes Asterix and Obelix had to live in the last point of resistance against the Romans, they would lose their hands at the behest of Julius Caesar .. Perhaps they would have died from a hemorrhage or gangrene.

The conquest of Gaul was not Caesar's only military achievement. Frank Fabian in "Biggest Lies Ever" tried to close the achievements of the "divine Julius" in the numbers:

Pliny says that 1.2 million people died in Caesar's wars, not counting the massacres during the Civil War. Welleyus Paterculus (historian friendly to Caesar) lists 400,000 killed in Gaul alone and as many prisoners. Plutarch lists a million killed and a million prisoners, also mentions 300,000 fallen Germans .

Caesar's wars cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. Pictured:the capitulation of the Gallic leader Vercingetorix to Caesar at Alesia in the Lionel-Noël Royer painting (source:public domain).

Attyla

The "scourge of God", before it began to whip the Roman Empire for good, dealt with the immediate family. His two young cousins, Mamas and Atacam, wisely fled to the Romans. After some time, however, they returned the fugitives to the leader of the Huns. Attila picked them up in the city of Cassium in what is now Romania ... and had them put on a stake.

A certain Constantius, Attila's secretary, whom the chief accused of stealing gold vessels, also ended up on the stake. The condemned were dying in agony. They could go on for days, if the stake missed the heart, it just came out with its back. In addition, the still living unfortunates were often attacked by birds of prey, without waiting for their death. Maybe that is why the French medievalist Michel Rouche entitled one of the chapters of his book on the Huns and Attila "Justice of the stake" ...

The chief, however, did not stop at the liquidation of his cousins. Around 445, he also murdered his brother Bleda. From then on, he could enjoy the position of sole ruler and focus on expeditions into the slowly dying Roman Empire. Attila's raids affected both its eastern and western parts. As one historian wrote, so many people were killed and so much blood was shed that no one could count the dead. Huns looted churches and monasteries, slaughtered monks and virgins.

Attila was as ruthless with his family as he was with his enemies. Pictured is the chief of the Huns in the painting by Eugène Delacroix (source:public domain).

The inhabitants of Metz in Gallia were extremely unlucky. The Huns under Attila unsuccessfully besieged the city. Although they hit the walls with a battering ram, they could not be broken, so after some time they left, looking for loot elsewhere. Meanwhile, a fragment of the walls of Metz collapsed little later. Upon hearing of this, the Huns returned and murdered most of the townspeople.

Dariusz the Great

The famous Persian ruler did not mince his measures. At the beginning of his reign, around 520 B.C., he had to deal with the rebellion of Babylon. Fortunately, he had his man in the city - Zopyros. To make him heard among the Babylonian leaders, Darius ... sacrificed a thousand of his people. He placed them in such a place that Zopyros, at the head of the Babylonian troops, could make a trip and slaughter them ...

As a result, Zopyros' shares increased, but not enough. He needed another success. This time, Dariusz assigned two thousand Persian warriors to the slaughter. After this spectacular action, Zopyros was entrusted with command of the defense of Babylon. And he, having the keys to the city gates, opened them to the Persians .

To achieve his goal, Darius the Great was ready to allow thousands of his soldiers to be slaughtered (photo:درفش کاویانی; lic. CC BY-SA 3.0).

Having recovered Babylon, Darius the Great had 3,000 of its most eminent inhabitants impaled. The loss of the city was tragic. Some of them were caused by ... the Babylonians themselves, who at the beginning of the siege murdered all women in order not to waste food and be able to defend themselves longer .

The list is much longer

Of course, you can try to add another bloody ruler from ancient times to this list. The Aassyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, who reigned in the 9th century BC, boasted, for example, of impaling prisoners of war. Nor were the innocents the infamous Roman emperor Caracalla, who died in 217 AD, or the Chinese emperor Szy Huang-Ti (Shi Huangdi) from the 3rd century BC.

Regardless of the composition of the statement, one thing draws attention. Caracalla and Attila have always been depicted as bloodthirsty tyrants (perhaps excluding Hungarians who considered themselves heirs of the Huns). On the other hand, Dariusz the Great, Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar are most often viewed through the prism of their military successes.

For example, while Attila is considered by most of the bloody tyrant, Alexander is seen as the great ruler. Meanwhile, his rule is an uninterrupted orgy of murders. The picture shows the monument to Alexander the Great in Edinburgh (photo:Stefan Schäfer; license CC BY-SA 3.0).

Responsibility for the deaths of thousands of innocent people usually remains in the background. And it is written casually that Darius "suppressed the rebellion of Babylon." While he actually sent 3,000 of his soldiers to the slaughter in cold blood, and then had another as many men stringed on a stake!

It may be answered that this was the price of creating every empire. However, it might be worth looking at the past from a different perspective as well. The history of conquest is not only a history of battles and victories, but also the history of countless victims sacrificed on the altar of exuberant ambition and lust for conquest.

Studies:

- Pancras Dijk, "Genocidaire slachting" onder leiding van Julius Caesar bij Kessel , "National Geopgraphic. Neerland - Belgie ”, 10/12/2015.

- Frank Fabian, The greatest lies ever, Bellona 2017.

- Krzysztof Głombiński, Herodotus portraits of oriental rulers , "Meander" vol. 35, No. 11 (1980).

- Peter Green, Alexander the Great , crowd. Andrzej Konarek, State Publishing Institute 1978.

- Aleksander Krawczuk, Gaius Julius Caesar , National Institute for them. Ossoliński 1972.

- Kazimierz Kumaniecki, Roman literature. Ciceronian period , PWN 1977.

- John Man, Attila. The barbarian who challenged Rome , crowd. Katarzyna Bażyńska-Chojnacka, Piotr Chojnacki, Amber 2005.

- Jean Markale, Vercingetorix , crowd. Hanna Olędzka, State Publishing Institute 1988.

- Michel Rouche, Attila and the Huns. The expansion of barbarian nomads 4th – 5th centuries , crowd. Jakub Jedliński PWN 2011.