The island of Spinalonga (actually Kalidón) is located in the north-eastern part of Crete in the picturesque Bay of Mirabello. Currently, it is one of the greatest attractions of the region, although its fame was actually built on stories of human suffering, rejection and slow death in torment.

In 1579, the Venetians built a fortress on the island, which was nicknamed invincible - and for good reason. When the Turks managed to capture Crete in 1669, the fort on Spinalonga remained beyond their reach, becoming a place of refuge from the new invader for many Cretans until 1715. It was then that the island finally passed into the possession of the Ottomans.

The turbulent history of Crete and the stubbornness of its inhabitants in the fight for independence ultimately led to its liberation from Turkish rule and the creation of an independent region in 1898. The last Turks left Spinalonga only in 1903, but the houses and streets they left did not wait long for new residents.

They were treated like the living dead, forcing them to leave their families and live in isolation. This was the everyday life of the lepers

The authorities of Crete decided that this area will be perfect as a leprosarium, i.e. a leper colony . In theory, this was supposed to be a place where the persecuted and marginalized sick people would finally create a real community . Here, they were to undergo medical treatments under the supervision of qualified personnel in peace and lead a more peaceful life among people similar to them - suffering from Hansen's disease.

However, what sounded idealistic on paper actually turned out to be a place full of pain, sadness and death.

The disease of unclean people

Leprosy has long been considered a biblical punishment for sins. Those affected by lepra were treated as social outcasts. They were ordered to wear rags, cover their faces and signal the approach of other, healthy people with the help of special rattles.

The lepers, especially in the Middle Ages, lost almost all rights. They were treated like the living dead, forcing them to leave their families and live in isolation on the outskirts of towns or villages. They were also placed in leprosariums that could be found almost all over Europe.

Over time, attitudes towards those affected by Hansen's disease began to change. Especially during the Crusades, when it spread among the Crusaders and marked the King of Jerusalem himself, Baldwin IV the Leper.

The fear of getting infected was so great that there were also cases of castration of men - in order to protect women and potential children.

Over time, attitudes towards those affected by Hansen's disease began to change. Especially during the Crusades, when it spread among the Crusaders and marked the King of Jerusalem himself, Baldwin IV the Leper. At that time, helping the suffering was considered a Christian duty. Of course, this did not equal the sudden removal of the stigma and general support of the sick. This affliction still caused widespread disgust and a terror that lasted in Europe until the 20th century.

Thinking about leprosy started to change gradually only in the second half of the 19th century with the discovery by Armauer Hansen of mycobacterium leprae responsible for lepra infection. The real breakthrough, which ultimately led to the elimination of inflammatory foci in Europe, was the appearance of the first treatment for leprosy in the 1930s. However, this, for many lepers, did not mean a quick exit from hospitals or leprosariums and returning to normal life. As many people from Spinalonga have found out.

Concentration Camp for Lepers

In October 1904, the houses of Spinalonga were already inhabited by 251 Cretan lepers. However, what was supposed to be an asylum place was more like a prison.

Due to the steep slopes, moving around the island was not easy - the steep streets and numerous stairs were difficult for patients who already had limb deformity . For this reason, some of them, instead of moving to more spacious houses in the interior of the island, lived in small and inferior standard buildings located closer to the coast. This was not the only assumption that only proved correct on paper.

In theory everything was planned, in practice nothing works as it should. Authorities say:We accommodated the sick as best we can, but the island's notoriety is spreading rapidly around the area. There is no electricity in Spinalonga, no running water. They are provided by old cisterns that still remember the Venetian times, but the water that collects in them is of terrible quality - dirty and full of germs .

There is a lack of basic medications, painkillers or disinfectants, which at that time were the minimum and maximum of what medicine could offer to lepers. New patients, usually handcuffed, are brought to the island by the Cretan police.

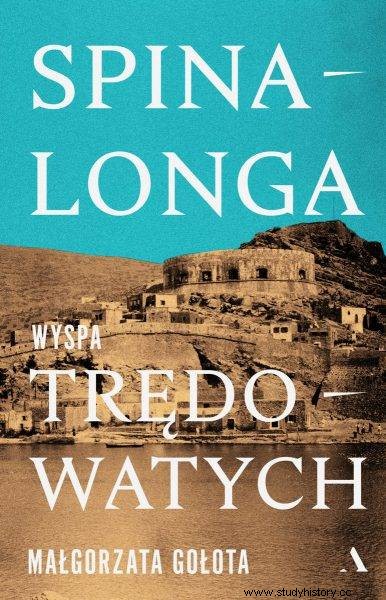

The text was created, among others based on the book by Małgorzata Gołota “Spinalonga. The Lepers' Island ”, which has just been released by Agora Publishing House.

Medical personnel, who were legally supposed to live on the island with the sick, came from land for visits. The only healthy inhabitants were the guards - convicts employed to keep order in Spinalonga. However, they soon took advantage of the sick by selling them food of dubious quality at exorbitant prices, and abused their power.

This led to the first rebellion of the inhabitants, which they finally fought for the eviction of the persecutors from the island, the abolition of curfews and the possibility of opening shops and cafes in the leprosarium.

With the incorporation of Crete into Greek territory in 1913 Spinalonga began to be flooded with sick people from other parts of the country, including the educated and wealthy people of Athens . Among other things, thanks to them, further changes took place on the island. Of course, their implementation was a laborious process, but the lepers gained a substitute for normalcy. This one, however, did not meet with the admiration of the foreign media.

Taboo that has become a tourist attraction

A Belgian journalist who visited Spinalonga in 1937 explicitly called it a concentration camp. Behind the beautiful stories of happy inhabitants, leading a normal life or getting married, there were stories of human suffering and neglect.

The healthy island-born babies were taken from their parents after testing. Their identities were changed and they were sent to orphanages in Athens, from where they ended up with new families. Many sick people had to take care of their wounds on their own for a long time, and the dead on the island were buried in nameless graves.

The island itself was not a friendly, safe haven either. Its land was far from the fertile land of the Lasithi plateau for which Crete is famous. The inhabitants paid for the occupation of Italians and Germans during World War II with starvation. However, one can speak of happiness in misfortune, because in many other leprosy in enemy territories massacres of the sick took place.

Many sick people had to take care of their wounds on their own for a long time, and the dead on the island were buried in nameless graves.

The end of the war, however, did not bring the lepers free. Although a drug has been available in circulation for some time, it has not been a guarantee of leaving Spinalonga. It was true that the government of the country did not know what to do next with the convalescents.

Those least affected were able to return to society. Unfortunately, many patients suffered from physical deformities of the body and blindness. Eventually, external pressure led to the closure of the island's leprosarium in 1957, and some of the convalescents were transferred to the hospital in Agia Varvara, where they lived in small houses until the 1970s, for which they had to pay for the construction themselves.

Currently, Spinalonga is one of the greatest tourist attractions of Crete. Every year it is visited by crowds of tourists who are presented with a polished version of the life of the sick in the colony. These stories inspired Victoria Hislop to write the novel "The Island", which was the basis for the Greek miniseries.

However, the real history of the inhabitants is blurred in the pages of history. The lack of proper documentation and the negligible amount of written memories made them a curiosity from a world no longer available to us.