The Episcopate is already sending out invitations to the celebration of the anniversary of the baptism of Poland. Two great ceremonial bells - Mieszko and Dobrawa - are waiting for the blessing, and the president is probably preparing his speech. There is only one problem. Probably everyone got the date wrong. And possibly the event itself as well.

The organizers of large (maybe even too big, considering that it is not an "equal" anniversary at all) behave as if it was obvious when, where and under what circumstances the baptism of Mieszko I. Even the specialists got carried away. . On my way to my family for Christmas, I listened to a radio conversation with an employee of the Museum of the First Piasts in Lednica. The representative of the respectable institution was not only convinced that the baptism took place on Easter 966, but also described in detail Mieszko's outfit, his gestures, and even ... the princely dressing room.

Of course, no information has been preserved in the chronicles about all these details. Comparative sources are also extremely sparse. Above all, it would be fair to admit that even the date seems far too far off.

Dobrawa as the Christianizer of Poland. Drawing based on a 19th-century lithography.

Are popular ideas good ideas?

The oldest Polish years give the year - 966 - but not the month or the day. Historians have wondered about the exact date for decades, and the thesis about Easter baptism was not necessarily popular because it was the best. She was helped by the fact that the popular author, Jerzy Dowiat, was behind her, and his work - briefly entitled "The Baptism of Poland" - was written in an accessible and concise manner. As a result, it has become the most frequently re-published and quoted study on the beginnings of Polish Christianity.

Professor Dowiat, at least in this particular book, did not try to be subtle. He stated categorically that Mieszko had joined the Lord's flock on Holy Saturday, April 14. In a way, such a term was self-evident, given the traditions of the Church. Loud baptisms of rulers usually took place just before Easter. But was that also the case this time?

Mieszko I as the first Christian ruler of Poland in a 19th-century lithograph.

Not Germany for sure

It is worth emphasizing that the overall findings of Jerzy Dowiat have not been accepted by the scientific community at all. Apart from the date, the author also specified the place of the events. In his opinion, Mieszko became a Christian in Germany, in Regensburg, as a place of an appropriate rank, having an impressive cathedral. This idea was not only widely rejected, but many publications even ridiculed it. And it is indeed very difficult to defend.

If the baptism had taken place in Bavaria, Bishop of Regensburg, Michael, would have been trumpeting left and right about his success. The information would infiltrate local yearbooks and chronicles. Meanwhile, the baptism of Mieszko was not noticed in German sources. It was mentioned only half a century later by the chronicler Thietmar. He also did not say a word about the fact that the event took place in Germany.

Baptism on the miniature included in "Vita gloriossime virginis Mariae atque venerabilis matris filii dei vivi veri et unici", Venice, 14th century.

As a rule, one should not draw conclusions from the silence of the sources, but in this case we have some really strong arguments. Thietmar was truly obsessed with the civilizational inferiority of the Slavs. What's more, he had a deep, even personal, grudge against the Piasts. He would not miss the opportunity to emphasize that in order to accept Christianity, the ruler of Greater Poland had to travel as far as Germany. The more so because the bishop of Regensburg, Michael, was a well-known figure to him.

It is fitting to invite friends

This mysterious silence of the sources sounds much stronger than it might seem. It allows you to reject the concept of baptism in Regensburg, but also forces you to think about the circumstances and date of the event.

Baptisms of rulers were ceremonies with an international tone. High-born guests were invited, crowds of bishops were drawn to concelebrate a solemn mass, gifts and congratulations were exchanged. In the case of Mieszko, one should expect a particularly grand setting.

Only a few or a dozen or so months earlier, the prince had visited the imperial court and was recognized as the official friend of Emperor Otto the Great. It was a title awarded extremely rarely, and the barbarian leaders - to which Mieszko was at that time - could never actually count on amicitia emperor. Otto made an exception for the prince of Greater Poland, so apparently he was sincerely interested in the further fate of the Piast state. Mieszko would be disrespectful to him if he refrained from inviting the imperial representatives (and perhaps the emperor himself) to his baptism.

There is no trace of a similar invitation. No mention of the German delegation sent east, no information about the baptism itself in the annals tracing the life of the imperial court. A strange thing, considering that Otto spent most of 966 in Germany, probably mostly on his Saxon estates. A stone's throw from Wielkopolska!

How about Christmas?

This fact forces us to rethink the date of baptism, especially since there are no sources for Easter. Christmas in 966 seems more likely than the date proposed by the County. Then the emperor was already in Italy and the news of Mieszko's baptism could have missed him.

Blessing of the baptismal water. "Franciscan Missal", 14th century.

In fact, however, no date should be excluded. Baptism could take place on any relatively important holiday or even on… ordinary Sunday. Where did this idea come from? Simply everything we know about the Christianization of Poland indicates that it was about one big makeshift.

The only such baptism

Mieszko's baptism only seemingly resembles similar ceremonies organized in other countries. In the case of Bohemia, Russia, Hungary, Denmark or even the state of Vistula, we always know the political circumstances of Christianization, and often also the names of the bishops who brought the new religion to a given country. It is standard that contacts with Christianity develop over several decades, Western culture gradually penetrates the given lands, and only the crowning of the difficult and long-lasting process is the prince's decision to convert. The Piast state is an exception, however.

There were no western preachers here, and no communes professing a new religion. Close relations with the Christian powers had only been established a few years earlier. Nobody asked Mieszko to be baptized - today we can say with certainty that neither the Czechs nor the Germans insisted on changing their religion. The prince of Prague, Bolesław, without hesitation, gave his daughter to a pagan in marriage, and Otto I the Great also had no problem with making a friendship with an idolater. Moreover, all of Mieszko's immediate neighbors were pagans:Pomeranians, Prussians, Silesians, Polabian Slavs. The pressure of Christianity was still not felt, and to reject the faith of the ancestors must have seemed a premature and highly unwise decision.

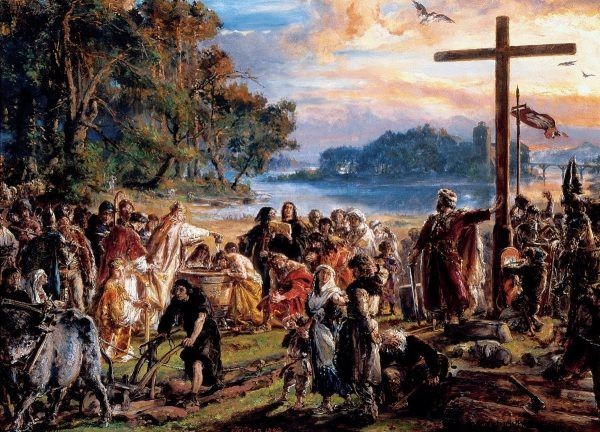

Introducing Christianity in the image of Jan Matejko.

If Mieszko entrusted Christians to God in spite of this, he was undoubtedly guided by emotions and personal convictions. This is what all later chroniclers claimed. And they knew very well who persuaded the prince to take such a radical step:Mieszko was baptized under the influence of his wife.

The merit of one woman

Dobrawa took advantage of the spouse's fears and ambitions. She knew that the leader was fascinated by Christian culture, but most of all - she was well aware of the fact that his authority hangs in the balance.

Mieszko waged a difficult war with the neighboring Lutycki Association and consequently lost this war. The Luthers plundered his state, won two battles recorded in the sources, and even killed their prince's brother. To counter their subsequent attacks, Mieszko entered into an alliance with the Czechs sealed by marriage. Now, in AD 966, the war had entered its decisive phase. Piast was preparing for a major battle. A confrontation that could, at worst, deprive him of his throne and life, and at best, make him the most powerful ruler in this part of Europe.

Baptism in Jordan on miniature from the codex of William of Nottingham, 14th century.

Multiple defeats had to shake Mieszko's trust in the old gods. And if not, at least they undermined the prince's conviction that at the time of the trial these gods would side with the Piasts, not their enemies. It all depended from that moment on, and Dobrawa no doubt took the opportunity to wrap her husband around.

In the stories that Mieszko listened to with interest, she began to refer to the armed triumphs carried with the name of Christ on her lips. She didn't have to go far. The battles of her father who united the Czech Republic, the successes of her uncle, Saint Wenceslas, but also a sea of blood in which the Slavic Elbe, conquered by the Germans, drowned. All of this happened with the blessing of the Christian God. Mieszko also had a chance to take advantage of His grace - it was enough to trust Him in time. And most of all:trust Dobrawa on time.

Duchess Dobrawa in the image of Michał Stachowicz - lithographer creating in the era of romanticism. The illustration comes from the book "Iron Ladies".

Big makeshift

The decision did not have to be the result of many months of reflection and preparation. It did not have to be preceded by fasts and a long catechumenate. Baptism could take place completely spontaneously, and the celebrant was not a bishop especially invited for this occasion, but a simple priest from Dobrawa's entourage.

As a result, no German hierarch could claim credit for the conversion of Mieszko, and the emperor staying in Italy learned about his decision only after the fact. Even Thietmar, well versed in Polish politics, was confused. He gave his readers two contradictory pieces of information about how many times Dobrawa had to break a post to win her husband's trust.

Paradoxically, the account of another chronicler, Vidukind, tells about the case the most. The man who created during Mieszko's lifetime praised the emperor's policy, yet he knew nothing about Piast's baptism. However, he provided a different piece of information. On September 22, 967, Mieszko won the great battle with the Lutykes. For the prince, it was an easy sign. The new God has just proved his power, and the new religion has just demonstrated its superiority over the faith of its ancestors.

***

Sources:

The article is based on the literature and materials collected by the author during the work on the book "Iron Ladies. The Women Who Built Poland. Find out more by clicking HERE . Selected bibliographic items below:

- W. Abraham, Organization of the Church in Poland until the mid-12th century , pub. 2, Wodzisław Śląski 2010.

- J. Banaszkiewicz, Dąbrówka "christianissima" and Mieszko a pagan (Thietmar, IV, 55–56, Gall I, 5–6) [in:] Nihil superfluum esse , eds. J. Strzelczyk, J. Dobosz, Poznań 2000.

- M. Dembińska, The model of a Slavic woman in the chronicles of Gallus Anonymus, Cosmas and Nestor [in:] Medieval and Old Polish culture. Studies offered to Aleksander Gieysztor in the 50th anniversary of his scientific work , ed. D. Gawinowa, Warsaw 1991.

- J. Dowiat, Baptism of Poland , Warsaw 1997.

- J. Dowiat, Baptism certificate of Mieszko I and its genesis , Warsaw 1961.

- G. Labuda, Duchess Dobrawa and Prince Mieszko as godparents of Piast Poland [in:] Scriptura custos memoriae. Historical works , ed. D. Zydorek, Poznań 2001.

- R. Michałowski, Christianization of the Piast monarchy in the 10th – 11th centuries [in:] Animarum Cultura. Studies on religious culture in Poland in the Middle Ages. Church-public structures , ed. H. Manikowska, W. Brojer, Warsaw 2008.

- G. Pac, Women in the Piast dynasty. The social role of Piast wives and daughters until the mid-12th century - a comparative study , Toruń 2013.

- A. Pleszczyński, The beginning of the rule of Bolesław the Brave [in:] Viae historicae. Jubilee book dedicated to Professor Lech A. Tyszkiewicz on the seventieth anniversary of his birth , Wrocław 2001.

- B. Sawyer, Women and the Conversion of Scandinavia [in:] Frauen in Sp ätantike und Frühmittelalter. Lebensbedingungen, Lebensnormen, Lebensformen , Ed. W. Affeldt, Sigmaringen 1990.

- J.T. Schulenburg, Forgetful of Their Sex. Female Sanctity and Society, ca. 500–1100 , Chicago 1998.

- D.A. Sikorski , The Church in Poland of Mieszko I and Bolesław the Brave. Considerations on the Limits of Historical Cognition , Poznań 2013.

- J.A. Sobiesiak, Bolesław II Przemyślida ( † 999) , Krakow 2006.

- S. Zakrzewski, Mieszko I as the builder of the Polish state , Warsaw 1921