Hitler's apparatus of oppression in occupied Poland could not function efficiently if it were not for informers. Do you think there were only a handful of them? Not at all. Only in the "capital" of the General Government, the Germans had hundreds of informers at their service

The invaders started building a network of informants in the town of Krak in the early autumn of 1939. The motives of people deciding to become spies were different. Some expected material benefits, others were forced to do so by blackmail. In Krakow, the Nazis could constantly count - throughout the war - on the help of about 800 to 1,000 agents and associates. As Professor Andrzej Chwalba writes in the book "Okupacyjny Kraków in 1939-1945":

On the list compiled by the Krakow counterintelligence [Armii Krajowej - author's note] from September 1944, 686 agents were found. Later, more were deciphered - 803 in total. The list was started by a buffet from the Main Railway Station. So for 300 inhabitants - 1 informant.

Such a small, such a big confessor can be

Agents and confidants were recruited from virtually all social strata and nationalities living in the city. They were Poles, Germans, Ukrainians and numerous Jews. In their ranks you could find real professionals, such as Danko Redlich, a pre-war communist agent who, after his "adventure" with the Gestapo, worked for the Security Office.

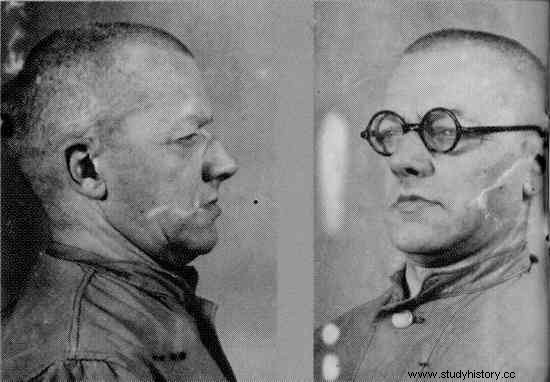

Sławomir Mądala (in the center playing cards with two scouts from the "Alicja" platoon, around 1943. Photo from the "Pomorska Street" guide by Andrzej Jeżowski (Historical Museum of the City of Krakow, 2011)

The Germans "inherited" some of their collaborators from the State Police. Broken members of the underground constituted a large percentage. One of them was, for example, sixteen-year-old scout Sławomir Wisala "Pirat", who, under the influence of torture and at the urging of his mother, who wanted to save his son, decided to cooperate with the Gestapo.

As a result, almost all of his teammates were arrested. For treason, he was sentenced to death by the underground Military Special Court. The sentence was carried out on March 31, 1944. The mother of "Pirat" was also killed. She was also an informer.

Henryk Wojciech Koppel, on the other hand, avoided the punishing arm of the Underground State. This, twice decorated with the Cross of Valor, a pre-war captain of the Polish Army, arrested in March 1941 under the influence of a brutal investigation, decided to cooperate with agents. As Grzegorz Jeżowski writes in the "Pomorska Street" guidebook:

He regularly provided information to lead officers Kurt Heinemayer and Rudolf Körner. As a result of Koppel's confidant activities, many people were deported to concentration camps, from where they never returned. Koppel denounced engineer Jan Gołąbek twice - first to the Gestapo, and after the war to the Security Office.

Another soldier in the service of the Germans was Roman Słonia, a soldier in the September campaign. His network, apart from working for the occupant, also dealt with criminal activities. The group, well-armed by the Gestapo, felt unpunished, as the skull-head guardians turned a blind eye to the criminal activity of the Elephants and his companions, pulling them out of jail every now and then.

Information given to the Germans by the pre-war captain of the Polish Army, Henryk Koppel (a photo taken during his arrest by the Germans), was the reason for sending many Cracovians to concentration camps. After the war, Koppel worked for the Security Office. The photo comes from the guide "Pomorska Street" by Andrzej Jeżowski (Historical Museum of the City of Krakow, 2011)

In the end, however, the scoop changed and the Home Army decided to intervene, using a trick. As we read in one of the chapters of the work "Krakow - Nazi Occupation 1939-1945":

In the spring of 1944, Kripo officers [German criminal police - footnote by the author of the article] arrested one of the members of the Słowni network under the pretext of a street brawl. Home Army soldiers worked in Krakow's Kripo, and they quickly took over the case. Officer Kripo, 2nd Lt. Stanisław Szczepanek "Janusz", a soldier of the Home Army, informed his German superior [...], that he arrested a bandit who, during the investigation, revealed a conspiratorial location.

This article has more than one page. Please select another one below to continue reading.Attention! You are not on the first page of the article. If you want to read from the beginning click here.

Rudolf Körner, a Gestapo officer to whom many informers were subordinated, including Henryk Koppel and Maurycy Diamand. The photo comes from the guide "Pomorska Street" by Andrzej Jeżowski (Historical Museum of the City of Krakow, 2011)

Then things happened very quickly. The officer, wanting to prove himself, sent - without consulting the Gestapo - his men to the address indicated. In the tenement house at 7 Blich Street, where the gang resided, there was a shootout which killed Roman Słonia and several of his men. Thus the Germans themselves became the executors of the sentences of the Underground State.

Many Jews also worked for the Nazis. The most numerous and dangerous was the network led by Maurice Diamand. It was worked out and liquidated only in the summer of 1944, which was only partly thanks to the Home Army. Diamand himself disappeared from Krakow in September that year. According to one version, he was murdered by the Germans. Another says that he survived the war and moved to Vienna.

The notorious Julian Appel, one of the most dangerous informers, also belonged to the same group. With time, he created his own network specializing in finding and handing over to the Germans hiding Jews and members of the Polish and Jewish underground. Although both the Jewish Combat Organization and the Polish Underground State passed the death sentence on Appel, it was not possible to liquidate it and he fled the city together with the retreating Germans.

Fighting informers

Stanisław Kostek Czapkiewicz "Spring", he was in charge of the Home Army network collecting information about informers. The photo comes from the guide "Pomorska Street" by Andrzej Jeżowski (Historical Museum of the City of Krakow, 2011)

Of course, the Union for Armed Struggle and then the Home Army tried to fight denunciation. In Krakow, the Home Army had a thriving intelligence and counterintelligence collecting information about informers. This was done by people led by Stanisław Kostka Czapkiewicz "Spring". Members of his network worked, among others, at the post office, intercepting denunciations. The underground soldiers working in Kripo also provided valuable information about the traitors. The obtained data was then repeatedly published in the underground press, which was supposed to intimidate German informants and warn potential victims.

Attempts were also made to influence the informers by means of more direct methods, making it clear to them that they were to cease their activities. When this did not work, they resorted to forceful solutions. During the entire war, several dozen informers were liquidated in Krakow. The first sentence was carried out on November 6, 1940 on a pre-war military police officer, Jan Platera. It was done by Jan Kostecki "Żywioł" and Jan Chromy "Delfin". The greatest intensification of actions against the capruses took place in 1943, later, due to the retaliatory repressions of the occupant, they mainly limited themselves to sending warning letters, using threats and punishing flogging.

Not only Krakow

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that Krakow was by no means an exceptional city in terms of the number of people working for the Germans. It is estimated that the Gestapo had approximately 60,000 agents and collaborators in occupied Poland.

As in the case of the "capital" of the General Government, they came from various social and national groups, but they had one thing in common:they had the blood of thousands of victims of the brown regime on their hands.

The scale of the usefulness of the bugs for the occupant is evidenced by the fact that it is estimated that 1/3 of those arrested or suspected fell into the Gestapo's orbit due to information provided by informers!

Many of them changed their "employer" after the war and went to cooperate with the communist repression apparatus, often reporting on the same persons denounced by the Gestapo.