“In the Czech land, he married the noble sister of Bolesław the Elder [Bolesław II], who in fact turned out to be what her name was. It was called Dobrawa in Slavic, which in German means:good… ”- wrote about the qualities of Mieszko's wife Thietmar of Merseburg. And although the malicious ones pointed out to the Czech princess her advanced age and shameless conduct, she was able to effectively turn our ruler's mind.

Unfortunately, the immediate reasons that led Mieszko I to be baptized are still unknown. In the available sources this event appears to be an accidental result of the concept of a Christian princess as wife. And it is precisely this randomness that has led historians to make endless deliberations and conjectures about the deeper causes of such a momentous event.

Although the malicious ones pointed out to the Czech princess her advanced age and shameless conduct, she was able to effectively turn our ruler over the head.

As the historian Andrzej Pleszczyński emphasizes:

in the textbooks Mieszko's decision is usually explained by political reasons, explaining, among other things, that he wanted to introduce his state to Europe, or that he wanted to strengthen his power by imposing one faith, in addition "modern". Such interpretations, however, are an attempt to rationalize, from our point of view, the motives of a solution that is not clear for us.

Moreover, perceiving such an important decision in this way, the Duke of Polan appears to be a calculated clairvoyant - knowing the future and calculating what is profitable from the point of view of the authorities and interests of the state. And however we do not appreciate Mieszko I, we cannot overdo peanuts in his honor.

Was Mieszko afraid of the Germans?

The fact is, however, that in the 60s of the 10th century the state of Polan found itself in a difficult position. And it is not about the threat posed by Emperor Otto I. Indeed, the extent of his power in the immediate vicinity could disturb the Polish prince. “The energetic and ruthless margrave Geron, the then most important Saxon noble, was just finishing his conquest of Lusatia. Earlier, with his significant participation, the Połabians (Obodrzyców and Wieletu) were defeated and tribute was imposed on them along with political authority "- notes Andrzej Pleszczyński.

Moreover, , the Czech Bolesław I Srogi became dependent on the imperial power in the south. However, this was where the momentum ended. It took time to develop new acquisitions and to fully subdue the all-time dangerous Polabian Slavs.

Mieszko's often stressed fears as a pagan ruler against the repeated invasions of the German knights can be put between fairy tales.

Also often emphasized fears of Mieszko as a pagan ruler against the repeated invasions of the German knights can be put between fairy tales . This backward projection of the later experiences of contacts with the western neighbor, intensified by the partitions and the Nazi onslaught, had nothing to do with the situation at that time.

And while Prince Polan could not have known that in the future, the adoption of baptism and Christianity would not protect his descendants from imperial expeditions, the example of the Czechs was well known to him. The southern neighbors were baptized at the end of the 9th century, and even so in the next century they had to face Germanic temptations.

Moreover, at that time the eyes of Otto I were focused on Rome. The conflict with Constantinople, questioning his imperial title, made him even move to the Eternal City for a while. So he probably was reluctant to push further east, and Prince Polan, protected by deep forests and swamps, could feel rather safe.

Crisis of faith

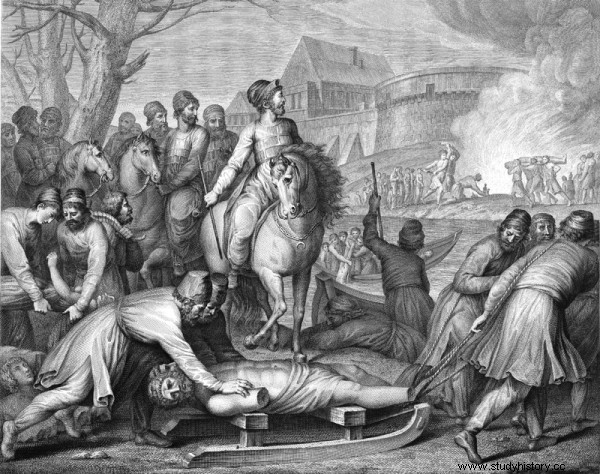

However, the threat was from a completely different angle. The chronicles mention the hard fights and failures of Mieszko in the clashes with the Wielets supported by the Saxon adventurer and the outlaw Wichman. Even the brother of the Duke of Polans, unknown by name, was allegedly killed in combat somewhere near the northern ends of the Lubuskie region.

Historians incline to the thesis that perhaps these unfavorable events prompted Mieszko to think what to do next. One cannot reject the suspicion that could then lose faith in the causative power of the guardian deities of his own people . It is well known that the subjects have always demanded from their ruler military successes and the related immediate, quick benefits.

The chronicles mention the heavy fights and failures of Mieszko in the clashes with the Wielets supported by the Saxon adventurer and the outlaw Wichman.

After all, it should be remembered that the system of exercising power at that time based on the princely team required constant costs of its maintenance. We know from the Arab traveler Ibrahim ibn Jakub that in addition to full support, the team received a monthly salary in silver, and additionally, if one of them had a child, the prince also paid him a salary. And in the case of weddings for the children of the teammates, the prince was responsible for the dowry and wedding gifts. So, as you can see, the expenses were huge and in order to meet them, "the ruler had to be a victorious leader" - emphasizes Pleszczyński.

The lack of triumphs in the field could, therefore, mean for those times simply the reluctance of heaven towards their leader - and people wanted to get rid of such a monarch as soon as possible. Moreover, Wieleci not only seemed to be richer and more military efficient, but also owned the famous sanctuary in Radogoszcz. And Swarożyc, worshiped in it, appeared to be more effective than the Polański pantheon.

Therefore, experiencing a specific crisis of faith and not having the possibility of expansion towards richer areas that would provide the loot necessary to support the team and the state, Mieszko turned to the south. But not to plunder, but to save my sovereignty peacefully.

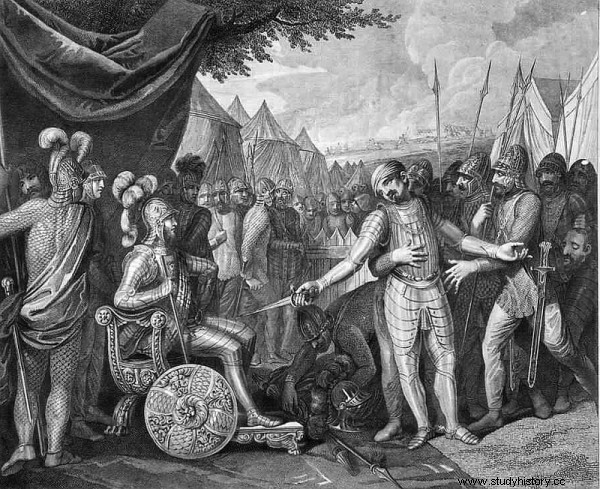

How good it is to have a neighbor

The rescue turned out to be… Czech Přemyslids who backed the Veilets. Under pressure from Otto I, they abandoned the Polabian allies - with whom, as some historians suspect, they had not maintained a closer relationship for some time - and switched to the side of the Duke of Polans.

The emperor probably counted on the joint help of Mieszko and the Czechs in the fight against the unbridled Wielet. Especially since, confirming the arguments of the researcher of the subject, Robert F. Barkowski, the "chronicles of that time" emphasize the imperishable hostile attitude of the emperor towards Wielet , which implies that he could not tolerate the Czech prince's closer allied ties with them. "

As a kind of guarantee of the new alliance, the marriage of the Duke of Polans with the daughter of the Czech ruler Bolesław I Srogi - Dobrawa was arranged.

As a kind of guarantee of the new alliance the marriage of the Duke of Polans with the daughter of the Czech prince Bolesław I Srogy - Dobrawa . This marriage "was probably determined not only by ethnic and geographical proximity, but also by chance. Bolesław I Srogi had a daughter of the age appropriate for marriage, ”emphasizes Andrzej Pleszczyński. And no one in the area had such a party.

Whatever it was, all sides benefited from such an arrangement - the emperor of allies in the battle on the Połabie, the Czechs of Mieszko's involvement in the battles in the north, distracting - according to the eminent medieval Henryk Łowmiański - his attention from the areas of Silesia and Lesser Poland, which were eagerly looked at by the Przemyślids, and finally by himself ruler of the Polans, saving his own throne by an agreement with his Czech neighbor.

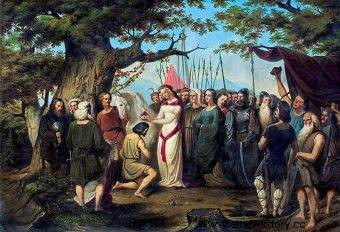

Polish baptism in the package

Based on Thietmar's accounts, preliminary alliance and marriage talks were held at the turn of the summer and fall of 964 in Prague. It is not clear whether baptism was among the terms of the covenant, or whether it was decided later. Some historians, led by the giants of Polish medieval studies, Henryk Łowmiański and Gerard Labuda, suggested that the most important role in the decision to be baptized was to be played by Dobrawa . And it was she who skillfully influenced her husband so that he would decide to adopt Christianity.

There is also a second group, with no less famous researchers such as Jan Dąbrowski and Jerzy Dowiat, who, however, take the power of Mieszko's baptism from the Czech princess. In the relationship between a pagan prince and a Christian, these historians made them discern an intention to change their faith - and this as part of the implementation of earlier findings. At the same time, the chronicle style prevailing at the time is indicated, according to which a pious woman tames a barbarian, saving his soul and repeating her own qualities.

Today, the thesis that the Bail's conversion resulted from genuine religious motives and not from cold political calculation is gaining more and more popularity.

In view of the scarce sources on baptism, it is difficult to clearly define what it really was like. At the Krakow market, one can probably risk a claim that probably each of the arguments raised had a raison d'être.

Nevertheless, today the thesis that the baptism of the prince resulted from genuine religious motives and not from cold political calculation to strengthen the prince's power is gaining more and more popularity. According to some researchers, the conversions of medieval rulers were not only about geopolitics and social engineering, but also about the question of which god "is more effective in winning the grace of heaven". And in view of the aforementioned probable crisis of Mieszko's faith in the protective spirits of his people so far, such a turn of events is quite possible. American historian Philip Steele even states explicitly:

Mieszko believed that the Christian God would help him more effectively in his worldly endeavors. And it really happened:after baptism Mieszko won one victory after another and eventually increased his territory almost fourfold .

So Mieszko would be our native Constantine the Great, successfully fighting under the sign of the cross.

New hostess

Whatever was behind Mieszko's baptism, the fact is that Dobrawa did not immediately enter the bridegroom. Sources suggest that it happened in early 965. She was definitely not thrilled about the political marriage with a pagan who "was so mired in the errors of paganism that, according to his custom, he took seven wives," wrote Gall Anonim. Moreover, as our chronicler continues:

refused to marry him unless he gave up this perverse custom and promised to become a Christian. When he agreed to abandon this pagan practice and accept the sacrament of Christian faith, the lady came to Poland with a great retinue of secular and clergy dignitaries, but did not first share the marriage bed with him, until slowly and diligently becoming acquainted with Christian custom and ecclesiastical laws, renounced the errors of paganism and passed into the womb of the Church-mother.

Gall seemed to suggest in this respect an earlier and similarly written record by Thietmar, according to which "this faithful follower of Christ, seeing her spouse plunged into multiple pagan errors, wondered hard about how she could win him for her faith."

It is worth noting that both Gall and the German historian rather unequivocally emphasize that the marriage took place first, and the baptism was the result of strenuous actions by the Czech princess.

It was certainly not easy for Dobrawa to adjust to the new environment professing polytheism. All the more should be appreciated her attitude and efforts to reconcile Mieszko for the Christian idea and "for the benefits of this glorious and desirable by all the faithful reward in the next life" - as Thietmar wrote in turn.

In the struggle for the soul of her husband, she did not hesitate to compromise her own piety. According to the chronicler from Merseburg, the daughter of the Czech prince voluntarily refrained from fasting so as not to immediately put off her spouse by the severity of the demands of the new faith . The latter, on the other hand, was to show for a long time an unfeigned indifference to his wife's efforts. Her diligence and risky endeavors eventually resulted in:

that the one who persecuted so severely repented and, at the constant urging of his beloved wife, got rid of the inherent venom of paganism, washing away the stain of original sin by holy baptism.

It is worth noting that both Gall and the German historian rather unequivocally emphasize that the marriage took place first, and the baptism was the result of strenuous actions by the Czech princess. It could therefore indicate that baptism was not a condition for the alliance. It is interesting, however, what would have happened if Mieszko had remained faithful to his current faith and tried to convince his wife to follow it. Would the wedding be annulled?

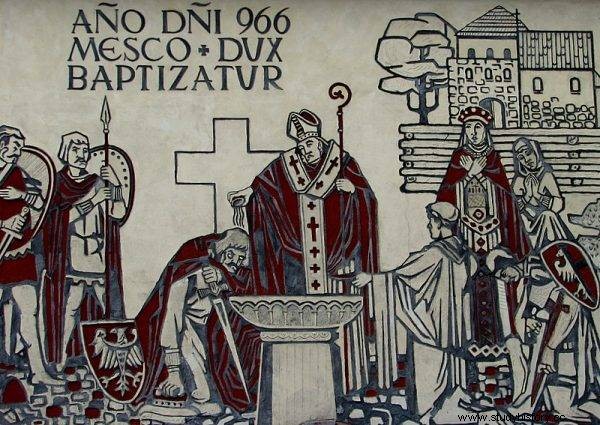

Mysko dux baptizatur

As there are endless problems with clearly identifying the causes and driving force of baptism, it is also troublesome to determine when a prince was baptized. And while the year 966 was adopted as a result of being prepared on the basis of available sources, it is in vain to look for the day date there.

In the course of stormy debates of historians, various proposals were made, for example, on December 25, argued by the adoption of Polish baptism on that day by King Franks, Chlodwig I. Ultimately, however in line with the eternal dispute over the superiority of Christmas over Easter, the latter option won . It was therefore assumed that it happened on the eve of the Lord's Resurrection, April 14 - because it was Holy Saturday that was customarily considered a day devoted to baptismal rites.

Just as there are endless problems with clearly identifying the causes and driving force of baptism, so is setting a date for baptism.

The place of this ceremony, so important for the history of Poland, also remained a problem for a long time. Some medievalists believed that the prince of Polan was baptized outside the borders of the Piast state. For example, Regensburg was indicated, perhaps even in the presence of the emperor himself as godfather.

Such a thesis was rejected, however, because such an important event as the admission of a prince of a neighboring country to the Christian rulers would probably be carefully recorded in the imperial chronicles. And certainly Thietmar, who did not like the Piasts, would not deny himself the satisfaction of emphasizing the fact that in order to receive the sacrament, the Piast ruler had to go all the way to the Reich.

Prague was also taken into account, but its candidature also lost its raison d'être due to the aforementioned silence of the sources. Ultimately, the focus was on the home yard and Ostrów Lednicki was chosen. It was there, near the Gniezno stronghold, that the baptismal basin was found, in which probably "Mieszko the prince was baptized".

Bibliography

- Barkowski R.F., Mieszko I and Dobrawa, or Poland's alliance with the Czechs , "They Speak Ages" 4/2016.

- Dowiat J., Baptism certificate of Mieszko I and its genesis , Warsaw 1961.

- Gall Anonim, Polish Chronicle , crowd. R. Grodecki, Wrocław 2003.

- Cosmas Chronicle of the Czechs , crowd. M. Wojciechowska, Wrocław 2006.

- Kóčka-Krenz H., Christianization of the Piast state in archaeological sources , [in:] Science in the service of man , ed. E. Dobierzewska-Mozrzymas, A. Jezierski, Wrocław 2016.

- The Chronicle of Thietmar , crowd. M.Z. Jedlicki, vol. 1, Wrocław 2004.

- Labuda G., Mieszko I , Wrocław 2002.

- Labuda G., Studies on the beginnings of the Polish state , vol. 1, Wodzisław Śląski 2012.

- Łowmiański H., Religion of the Slavs and its fall , Warsaw 1986.

- Pleszczyński A., Baptism of Mieszko I - a conscious choice or a political necessity? , "They Speak Ages" 4/2016.

- Steele P.E., Conversion and baptism of Mieszko I , Krakow 2016.