The stories of women who were raped during the uprising are rarely spoken of. This is a difficult and painful topic. Neither the injured ones nor the people who were forced to witness their tragedy wanted to return to it. They usually talked about the tragedies that they experienced for the first time only after several decades - already at the end of their lives.

If they talked to journalists, historians or researchers of the topic, they repeatedly added that they wanted to remain anonymous, and that the memories could only be published after their death. Sometimes, being ashamed of what had happened to them, they emphasized that the story was about someone else, most often girlfriends. However, most women never made up their minds to confide. They took their traumatic experiences with them to the grave.

On the other hand, those who even wanted to share their stories often did not have the opportunity to shout out the truth about what happened. It is known that the world in such cases most often turns its eyes and refuses to listen. Not every truth is convenient for those who want to promote a specific thesis or - worse - write a new version of a story.

Unfortunately, the fact that for so many years the topic was kept in silence, we did not realize how great was the scale of the crimes of this kind at that time. deal with this traumatic experience. While browsing the literature on the uprising, you can find general information about what happened in Zieleniak, in Ochota hospitals, in Wola, the Old Town, Marymont and Czerniaków. But these are mostly just statistics. Without stories, emotions, faces of thousands of abused girls, teenagers, mature women and even old men.

It is even more surprising that in so many works, even those written by women participating in the uprising, the word rape did not appear for years. It was replaced with the term:German bestiality, without elaborating on the topic or limiting it to one or two sentences. Sometimes enigmatic expressions were used: there was bestiality; she was taken by the Germans; she came back the next morning.

Just don't tell anyone…

Those of the women who tried to touch the subject a little more wrote almost always anonymously:

We are suffocated by the atmosphere of reproach, mockery and mockery of German soldiers, pushing us into misery of incredible humiliation and disgrace. An unbearable burden crushes us to the ground.

Probably some part of this was due to the upbringing of the Columbus generation. Back then, some things were simply not spoken of loudly. And the fact of being raped meant stigmatization, disgrace and social ostracism. Sometimes also with contempt or even mocking laughter, not to mention indiscriminate jokes that some gentlemen allowed themselves to do.

Many women chose death instead of falling into the hands of the torturers. The pictorial photo shows the murdered people in Wola

It is surprising, however, that, even today, little is said about the rape that took place during the uprising. Why? A torn dress is not a topic on which a legend is built. There is no pathos, no heroism, no greatness here. Nobody will build a monument for a raped girl. It cannot be boasted. Her death is not beautiful. Therefore, most often it is not talked about at all. Or he mentions quietly and shamefully.

There are other reasons why this difficult topic has been so seldom addressed. Some people were afraid that they would be able to cope with the emotions of the interviewees. Others hid their own delicacy, claiming that the most intimate sphere of women's privacy should not be violated, or they were not consciously touching taboos, not wanting to expose themselves to anyone. Thus, the topic practically did not exist for years. And those who experienced sexual abuse were left alone with their trauma. No support, no help, no right to tears, no acknowledgment of harm, or no opportunity to shout out the truth about what happened then. "Do not tell anyone!"; "Don't go back to it!"; "Forget it!"; "Start all over again!"; "Just keep on living!" These words were constantly heard by women from people to whom they told the truth about what had happened. But this approach only deepened their drama. After all, you cannot open a new chapter unless you have closed the previous one. Live in the present and think about the future if stuck in the past.

Some of the wronged women tried to rebel. Let us scream! - they demanded. But when it turned out that no one wanted to listen to them, they sank deeper and deeper into themselves and the nightmare they experienced. Years of neglect cannot be undone or made up for. However, it is worth describing the stories that were saved. Especially since showing the individual drama of a particular woman - her fear, helplessness, harm and trauma - provokes reflection. It does not let the drama be indifferent. And most importantly - it brings back the voice of thousands of abused, often nameless women for whom there was no place in the history most often written by men.

The Dirlewanger soldiers committed brutal rapes and murders of women during the uprising

It is amazing that it was so rarely even mentioned how much during the uprising young women were afraid to fall into the hands of the enemy, especially the gloomy roners or the equally brutal soldiers of the Dirlewanger brigade, who were mainly recruited from among criminals and poachers and allowed war crimes, including extremely cruel rapes. Terrified teenagers, seeing a gang of drunken soldiers approaching the building, asked in a whisper of older women:isn't "it" worse than death? This panicky fear was written by Teresa Sułowska-Bojarska, alias Dzidzia-Klamerka.

One day, she literally escaped from the hands of the Germans at the last moment. When she reached the quarters and finally felt safe, she began to sob terribly. Her tense nerves were soothed with a calm and wise conversation by the girl's commander - Kazimierz Eyssmondt, alias Marian.

I started crying. I don't know why I couldn't hold back the tears, they just kept flowing. I was shaking, I was ashamed to be shaking. He stroked my torn hair, calmed me down, explained that it was all right, nothing happened ... I don't want to be raped, I'm afraid, I'm terribly afraid. Marian was surprised by nothing. He was not scandalized, he did not rebuke, he even said that he understood. Silence and something about human dignity. Only what he can bear falls on a man. So even rape can be survived with dignity, because nothing can take it away.

He ended this conversation with the suggestion that Teresa should protect herself from hatred, because nothing destroys a person as much as this feeling. (….)

Hell in Zieleniak

When it comes to rapes committed during the Warsaw Uprising, the slogan Zieleniak appears as a kind of symbol of the tragedy that happened then. Before the war, this place was a marketplace, while in the summer of 1944, the Germans organized a so-called assembly point here, where the civilians of Warsaw were gathered.

A kind of selection was made here, accompanied by countless executions. Those who survived were taken to the Western Railway Station and from there to the transit camp for civilians in Pruszków. However, Zieleniak became, above all, a place of mass rapes committed mainly by roners on children, girls, young and mature women, and even on elderly women.

Command of the RONA brigade

The knowledge about what happened in Zieleniak can be obtained from the accounts of the participants and witnesses of the events. One of such memories belongs to Maria Adamska:

It was terrible at night:women were dragged to be raped by shining flashlights in the face. It was then, on the first night, that two roners approached me. I was combed, not too dirty yet, so I looked possible. One of them said a vulgar "compliment" to me and started tugging at my hand. But my son, screaming terribly, would not let go of me. One of the roners looked at me and said:

- Leave her alone, maybe some younger one.

(...) It was well known that the girls who resisted were murdered in a brutal way. We heard a call for help, someone was calling for God, someone was praying. These screams were mixed with the screams of the roners and single shots.

Mrs. Wolf told the story of an eighteen-year-old girl raped in front of people by five roners. As she screamed, her mouth was gagged with biscuits. When she begged to finish her off, one of the soldiers escorted her to Zieleniak. The roners, the soldiers of Bronisław Kamiński, called the Ochota hangman, also committed cruel rapes on women who had just given birth.

It was common practice then to kill newborns, for example by asphyxiation. The sight of mothers mourning their children has become part of everyday life in Zieleniak. So are the corpses of martyred women lying along the wall surrounding the area.

Another memory of this terrifying place was left by Wiesława Chmielewska. Her account is complementary to the earlier stories, but also highlights the fact how many women, having no other choice, consciously chose death.

Ronats, walking among the crowd gathered in the square, plundered all valuable things. They also took women they liked. I remember this fact:the roner pulled the woman out of the crowd, she did not want to go, so he dragged her by the hands, and she cried for help:- Brothers, sisters, do not give me to the criminal. Nobody helped. The woman jumped up, stood, hit the rider twice in the face, he took out a pistol and shot her.

Bronisław Kaminski was also called "the executioner of Ochota"

These accounts emphasize the scale of the drama of women and the mass nature of the phenomenon. They also show how terrible the whole square was at that time. Almost every memory stressed that the nights were the most horrible. Drunken roners walked among the people, shining torches on their faces. They didn't care if they were stomping on the seated people or trampling on little children. If they saw a young woman, they immediately pulled her out of the crowd.

There were constantly screams, groans, pleas for mercy, cries for rescue, single shots and laughter of drunk men. From time to time, there were also requests to see a doctor.

It was normal…

On the other hand, during the day, soldiers usually dragged women to school at 93 Grójecka Street. They were raped, beaten and often killed there. In order to protect the youngest girls, they were hidden under blankets, quilts or coats on which other people - most often small children - would sit or lie down. Some women wore unsightly makeup to make them look seriously ill or unattractive. Zofia Piotrowska reported on what happened at Zieleniak:

On August 8, I saw the following:a married couple with a child was sitting next to us (…). The roners came for my wife. The husband started screaming, tried to protect her, but in vain. The bandits threatened to kill him. Then he said:- Sophie, go! That was awful. After some time, she came back. She was beaten, her clothes were torn, and she was crying spasmodically. Nine roners raped her. Her husband reassured her. On another day, I witnessed the death of an eleven-year-old girl, raped and beaten by the roners. She was dying by the wall, her mother was kneeling and crying beside her.

(…)

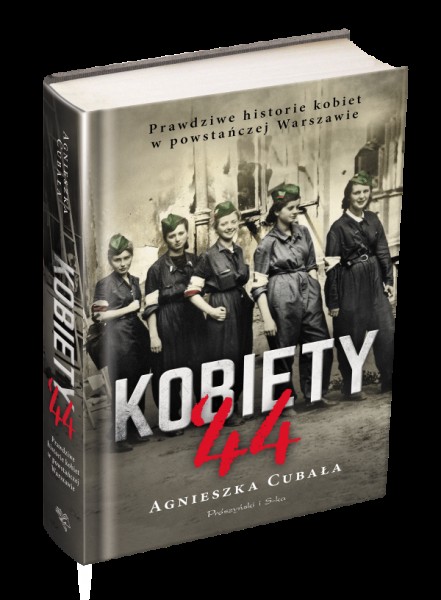

The article is an excerpt from the book Women `44. Real stories of women in the insurgent Warsaw, which was published on the market by the publishing house Prószyński i S-ka

When reading the accounts of women who came across Zieleniak, most often one can come across the words that it was terrible,

tragic, even horrible. And almost all the young girls were raped, but they just managed to avoid this fate.

Someone helped hide, made the escape easier, took pity. This version of events is of course likely, but it clashes with what other women are saying. Those who admitted being hurt. Hearing this version of events, they most often repeat one of the following sentences with understanding:

- They are ashamed to admit it. Please do not believe that anyone there could have avoided such a fate. Each of us

had to go through this. It was inevitable ... It was normal ...

Source:

The article is an excerpt from the book Women `44. Real stories of women in the Warsaw Uprising, which has just been released on the market by the publishing house Prószyński i S-ka