The most powerful kings pleaded with her for intercession and advice. Popes resorted to her for help. She was the richest woman on the continent. But she was also a proud daughter of the Polish Piast family. Do you know who we are talking about?

Nobody expected great things from her. When she got married, she was nothing more than a bargaining chip in the political scuffle. The Hungarian monarch, Karol Robert, who had great connections in the papal curia, helped to win the royal crown for Władysław Łokietek. In return, the Polish prince - and from 1320 the king - strengthened his alliance with his southern neighbor, and even offered to give him one of his three daughters as a wife.

Thus, in the same year, 1320, fifteen-year-old Elżbieta Łokietkówna became the Queen of Hungary.

She was only supposed to be an extra; a beautiful background for an overbearing husband. However, the older and more sick Karol Robert became, the more she herself was taking the helm of the government. After ten years, no one had any doubts that in Hungary the queen should be treated in the same way as the king. Or maybe even more.

1. She was the most influential woman in the history of her country

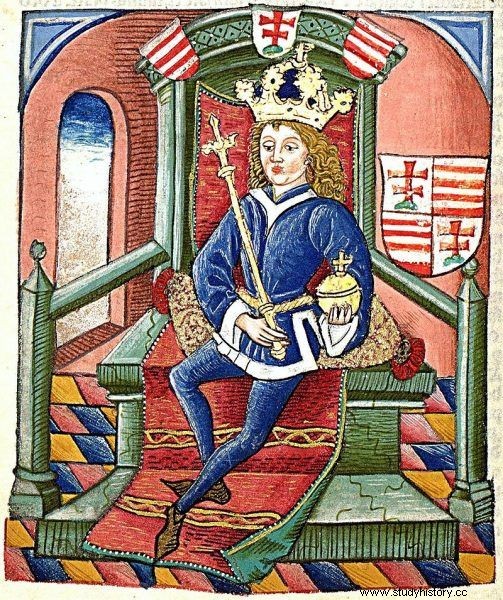

In light of ancient traditions, each queen was the number two in Hungary, right after her husband. It was crowned with the same Saint Stephen's crown that gave authority to the rulers. And at least under the law, the ruler had grounds to act as the head of any official, baron, or land administrator. This theory has never been tested in practice. Until the times of Elżbieta Łokietkówna.

Elizabeth enthroned. Queen's seal made immediately after her coronation. Illustration from the book "Ladies of the Polish Empire" by Kamil Janicki.

Piastówna settled territorial disputes, and its people measured and confirmed the borders of noble estates. The ruler also took care of the monasteries, she provided patronage to dear courtiers and knights. Finally, she defended the rights of despised women. For example, in 1333 she issued a document in which she scolded officials for trying to rob a helpless widow of what her husband had left her.

As if that were not enough, there are mysterious "edicts" issued by Elżbieta Łokietkówna, probably without any consultation with her husband. The queen ordered officials to return illegally seized properties, rewarded damages, imposed fees on her subjects, freed her from burdens ... In a word, she did everything that would traditionally be considered the prerogative of the king and no one else.

2. She wrapped her son around her finger, becoming the strongest and most independent queen of the time

Her all-powerful position grew even after her husband's death. When in 1342 the sixteen-year-old Louis (the future Louis the Great) took power, it was even difficult to say whether she was his irreplaceable helper, or rather - he disappeared in the shadow of his mother in real power.

Many of the documents of the new monarch contain the assurance that they were issued "in accordance with the gracious will of the brightest and most honorable lady, Elizabeth, Queen of Hungary, our mother." The Ruler has the main seal of the kingdom (allowing her to make virtually any decisions on behalf of her son), and her subjects often ask her directly to confirm this or that disposition of the king. There are also situations where courts change their sentences "for fear of the Queen Mother."

"She had such power as none of the Hungarian queens and only the character of her and her son should be ascribed that for this reason there was no disagreement between them" - emphasized one of Louis' biographers.

The queen-mother also consistently controlled Hungarian diplomacy. She contacted her neighbors, the Pope, the Italian relatives of her deceased husband ... Nobody - in the country or abroad - had any doubts that she had to be reckoned with.

Louis of Anjou. A thumbnail from the so-called "Illustrated Chronicle".

3. She was the richest woman on the continent

Soon after her husband's death, Elżbieta Łokietkówna set off on a journey to Italy. It was accompanied not only by a magnificent retinue, but also by a cavalcade of heavy carts filled with inexhaustible treasures. The monarch was dragging with her almost seven tons of silver and five tons of gold. To say it was a fortune is like saying nothing!

For comparison, the king of England from his entire state, from all duties, taxes and fees, had an income several times lower. It would take over three years to accumulate a similar fortune. The king of Poland, clearly poorer than an islander, would have harvested that much, but in six or seven springs. Even the true Croesus ruler of France accumulated a similar sum for almost a year, squeezing it out of millions of serfs and dozens of wealthy cities.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth did not carry all the treasures of her own kingdom. It was said that her inexhaustible fortune was her… pocket money. Appropriations needed to cover "current expenses" related to travel abroad. And this one and only episode in her life is enough to illustrate a fact that no influential man of the fourteenth century raised any doubts. In terms of wealth, not a single woman in Europe could compare with Elżbieta Łokietkówna.

The amazing story of women who built the Polish power. Jadwiga Andegaweńska and her predecessors in a new book by Kamil Janicki:"Ladies of the Polish Empire".

4. She was not afraid to put up the heir of Saint Peter himself

The mountains of gold that Elizabeth brought to Italy helped to bribe Pope Clement VI himself and lead to the proclamation of one of the monarch's sons, Andrew, king of Naples. However, the teenage dynasty died in an assassination attempt just before his coronation, with the knowledge (or even at the instigation) of his own wife - the Neapolitan heir to the throne, Joan.

Łokietkówna knew that such a heinous crime required the highest punishment. Meanwhile, the Pope torpedoed the investigation and even took care of the alleged murderer. In response, Elżbieta sent a letter to the curia full of venom and open threats. She reminded the Holy Father that "the Hungarian house is so powerful that any ruler would wish to join it" in an alliance. And that "if there is a dispute with the Pope, it is not the Hungarian house that will withdraw from the Church, but rather will be driven away by the Pope."

She did not hide what her true opinion was. Andrew's blood was shed not only under the Pope's watchful eye, but also with his consent and "with his protection". She gave Clement VI a last chance to atone for his sins and hand over the direct perpetrators of the crime. When, instead of meek consent, she heard empty phrases about justice that would surely be meted out, she proved that it was not allowed to play with it.

The tragic end of the would-be king, Andrew of Anjou. Painting by Karl Bryullov.

Ludwik Węgierski set off for Italy and conquered Naples in an express campaign, and sent those suspected of participation in the conspiracy of the local princes ... directly to his mother's court so that she could deal with them properly. In Italy, it did not survive solely due to the outbreak of the Black Death epidemic. Finally, the humble pope begged Łokietkówna herself to give up the fight.

5. The most powerful men of the Christian world flattened themselves before her

It is difficult to understand how much the good word of Elżbieta Łokietkówna weighed. And how much other rulers wanted to please her. Take, for example, those who control trade in the Adriatic and have the strongest fleet in this part of the continent, the Venetians. The Doges pleaded with Elizabeth more than once.

They sent her letters, gifts, and sent their best galleys for her, so that she could travel on the sea quickly and comfortably. And all this so that the powerful queen-mother would like to whisper a good word to her son about the Venetians. Or even better:she should look at her neighbors more favorably.

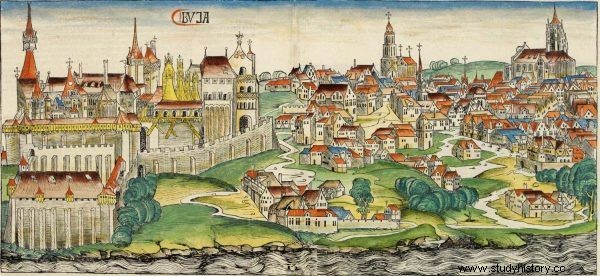

Hut. Favorite city of Elżbieta Łokietkówna and her headquarters.

6. Popes begged her for help. And many times

In 1376, when Elżbieta Łokietkówna was already over seventy years old, Saint Gregory XI sent her a letter, almost like a humble supplication, in which he asked her to convince her son to make concessions in a dispute with the papacy.

The Pope did not know the Hungarian queen personally. But he knew what was just as obvious to all his predecessors in the last half-century:if you want to run errands in Hungary, hit the Almighty Elizabeth straight.

7. It settled conflicts between the strongest dynasties

In the mid-50s of the 14th century, there was a serious conflict between Charles IV (King of Bohemia and the newly crowned Roman Emperor) and his Austrian neighbor, Albrecht II Lame of the Habsburg family. Pope Innocent VI obviously asked the Hungarian queen for mediation.

Charles IV of Luxembourg. He didn't understand that some women shouldn't be messed with…

Łokietkówna assumed the role of a mediator and quickly led to a ceasefire. Knowing that the iron had to be forged while it was hot, she then went straight to Vienna and there soon replaced the truce with a peace treaty. Albrecht trusted her intuition completely. Charles IV was stunned by her artistry. He was also so grateful to her that he invited the Hungarian queen on a joint pilgrimage to Aachen.

Elizabeth not only agreed, but overshadowed the imperial majesty with the splendor of her retinue. On her journey through Germany, she was accompanied by seven hundred wonderfully decorated horsemen, including many bishops and Piast princes from Silesia.

8. She almost robbed the emperor of the crown

Charles IV stayed with Piastówna for three weeks, feasting together with the monarch every day, having fun, conducting disputes. He recognized her intellect, observed her exceptional class and legendary generosity. Nevertheless, he did not draw the right conclusions from this journey together.

A few years later, the emperor began a behind-the-scenes game aimed directly at Elizabeth. The Queen was the regent of the kingdom of Dalmatia from 1358. The picturesque land was annexed to Hungary as a result of the victorious war with Venice, and King Louis, who understood his mother's talents well, gave her a new prize and full power over her. Meanwhile, Charles IV, seeking to restore the balance between the powers, intended to do his best to bring the maritime republic back to Dalmatia.

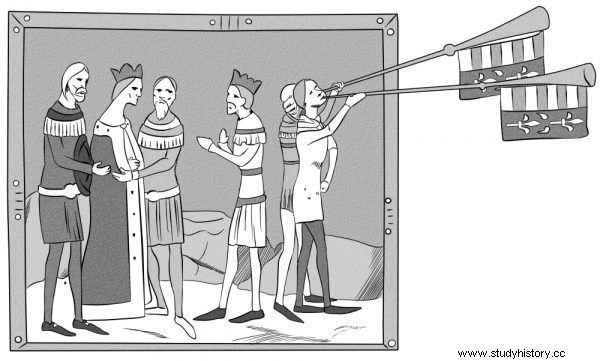

The coronation of Elżbieta Łokietkówna. Miniature from the so-called "Illustrated Chronicle", redrawn by Anna Pietrzyk.

Elizabeth was never satisfied with half measures. As soon as the agents informed her that Charles IV was planning to get her out of the Dalmatian properties, she decided to give him the same poison he had prepared for her. If the emperor got along with her enemies, she hit straight at his competitors.

She has overwhelmed the Habsburgs, who recently served Charles faithfully. She traveled personally to Bavaria by reconciling the princes there and including them in his anti-imperial coalition. Suddenly voices began to rise that it might be time to take Charles IV's crown away and make some more suitable candidate the emperor. And most likely it was Elizabeth who was actually behind these exhortations. A woman you really had better not to mess with.

Are you interested in this text? Its author also runs the "Wielka Historia" channel on YouTube.

***

It is impossible to list all the successes and all the fascinating episodes in the life of Elżbieta Łokietkówna in one article. It was thanks to her that Casimir the Great remained on the throne and earned his nickname. She helped make Poland a superpower. Even the famous feast at Wierzynek's was her direct merit. Finally, almost on her own, she made Jadwiga Andegaweńska the Polish king.

You can read about all this in my new book: "We will give the Polish empire". You can buy it today at empik.com

Holy queens who fell in love with the authorities. The fascinating story of Jadwiga Andegaweńska and her predecessors:

Selected bibliography:

The article was based on materials collected by the author during the work on the book "Ladies of the Polish Empire. The Women Who Built a Power " . Some of these items are shown below. Full bibliography in the book.

- Dąbrowski J., Elżbieta Łokietkówna 1305-1380 , Universitas, Krakow 2007.

- Dąbrowski J., The last years of Ludwik the Great 1370-1382 , Universitas, Krakow 2009.

- Engel P., The Realm of St. Stephen. A History of Medieval Hungary 895-1526 , I.B. Tauris, London-New York 2001.

- Fijałkowski A., Medieval royal coronations in Hungary and Poland , "Przegląd Historyczny", vol. 87, issue 4 (1996).

- Gyula K., Károly Róbert családja , "Aetas", vol. 20 (2005).

- Kozłowski W., The origins of the 1320 Angevin-Piast Dynastic Marriage , "Studies in the History of the Middle Ages", vol. 20 (2016).

- Lendvai P., Hungarians. A thousand years of victories in defeats , International Cultural Center, Krakow 2016.

- Small C.M., Joanna I of Naples [in:] Medieval Italy. An Encyclopedia , eds. C. Kleinhenz, Routledge, London-New York 2004.

- Sroka S.A., Anjou's reorganization of Hungary , "Kwartalnik Historyczny", vol. 103, issue 2 (1996).

- Sroka S.A., Elżbieta Łokietkówna , Homini, Bydgoszcz 1999.

- Sroka S.A., Elżbieta [in:] The Piasts. Biographical Lexicon , edited by K. Ożóg, S. Szczur, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Krakow 1999.

- Sroka S.A., Pilgrimage of Queen Elizabeth the Short to Rome in 1343 , "Peregrinus Cracoviensis", issue 4 (1996).

- Sroka S.A., From the history of Polish-Hungarian relations in the late Middle Ages , Universitas, Krakow 1995.

- Szajnocha K., War for the honor of a woman [in:] the same, Historical Sketches , vol. I, Polish Word, Lviv 1901.

- Śnieżyńska-Stolot E., Studies on the culture of the Hungarian court of Queen Elżbieta Łokietkówna , "Historical Studies", vol. 20 (1977).

- Historical Life of Joanna of Sicily, Queen of Naples and Countess of Provence:With Correlative Details of the Literature and Manners of Italy and Provence in the Thierteenth and Fourteenth Centuries , Vol. I-II, Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, London, 1824.