"Polishness is and will remain a hostile element" - emphasized Eugen von Puttkamer, president of the Poznań province. "Beat the Poles. There is nothing left for us to do but exterminate them, ”echoed Otto von Bismarck. How big of a Germanization campaign did they implement?

Germanization is a policy of Prussia carried out during the partitions, aimed at the denationalization of Poles and the settlement of the conquered territories with German population. The creator of the Germanization policy was Frederick II the Great, the initiator of the partitions of Poland.

The seizure of western Polish lands was treated as Prussian raison d'état. This was clearly expressed in 1831 by Field Marshal Karl von Clausewitz:

A small part of the Polish lands that fell to Russia is a matter of convenience for her, because it connects its northern and southern provinces. Austria's share is a luxury item because it has sufficient coverage in the Carpathians and can do without Galicia. On the other hand, the Prussian part is a living organism without which the state organism could not exist for a long time. Therefore, it is impossible to opt out.

A painting by Wojciech Kossak from 1909 entitled "Prussian rugs".

The factor that could stand in the way of these plans was the activity of Poles, their striving to regain independence, which was reflected in the armed struggles and the implementation of the organic work program aimed at self-modernization of Polish society .

South Prussia instead of Greater Poland

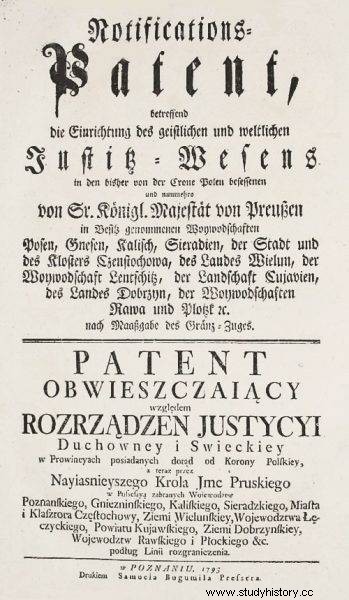

The Germanization policy, except for short periods of some easing of the course, was conducted with all consistency. A symbolic step was the introduction of the German nomenclature. And so, after the Second Partition, part of Greater Poland, incorporated into the Hohenzollern monarchy, was renamed South Prussia (Südpreussen). Crowds of Prussian officials came. Poznań became a significant garrison city. Efforts were made to give the city a German feel.

Prussian announcement on the second partition of Poland

The outbreak of the Kościuszko Uprising, supported by the local population, and then the Napoleonic era, when Greater Poland became part of the Duchy of Warsaw, made it clear to Prussia that Poles would not accept the loss of independence.

By decisions of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the western and central part of Greater Poland fell within the borders of Prussia. There was a short period of easing the partition's policy. Wielkopolska was named the Grand Duchy of Poznań. A quasi-autonomy was introduced, the symbol of which was the dignity of the king's governor, which was exercised by prince Antoni Radziwiłł, who was related to the royal family by marriage with the cousin of King Frederick William III Luisa.

On the other hand, in the bureaucratic nomenclature, this territory was called the Poznań Province ( Provinz Posen ). A visible sign of Prussian rule was the erection of huge fortifications in Poznań in the years 1828-1872, with the citadel at the forefront.

Increasing the Germanization action

The outbreak of the November Uprising and the large participation of volunteers from Greater Poland convinced the invader of the lively feelings of independence. In response, the authorities tightened the Germanization course. The consequent Germanizer Eduard von Flottwell stood at the head of the province, who formulated his plans as follows:

During my activity here in the above-mentioned period, I considered it necessary to understand the task of the provincial administration in this way:to support and consolidate its internal ties with the Prussian state, to slowly remove the directions, habits and inclinations that oppose this solution, which are characteristic of Polish inhabitants, so that more and more the element was spreading German…

In practice, this meant repressions against the participants of the November Uprising, prison, sequestration of property, Germanization of the judiciary, administration and education, as well as the Catholic Church.

Antoni Radziwiłł. Prince-governor of the Grand Duchy of Poznań

In the latter case, a dispute over bringing up children in mixed denominational Catholic-Protestant marriages breaks out. The Church held that regardless of the religion of the parents, the children were to be brought up in the Catholic spirit. The authorities took the position that the boys were to be brought up in the faith of the father, the mother's girls. Against this background, there was a dispute with the archbishop of Gniezno and Poznań, Marcin Dunin. As a result, in 1839, the archbishop was thrown into prison. There have been riots.

Dunin left prison in 1840 after his accession to the throne of Frederick William IV. However, further repressions soon fell on Polish society. The source was the discovery of conspiracies. Their participants were prosecuted in Berlin in 1847. There were 254 defendants in the bench. 120 conspirators were sentenced. The Spring of Nations brought them freedom.

Revolutionary gains

The period of the Spring of Nations is a short-term relaxation of the Germanization course. There is a project of the so-called reorganization of the Grand Duchy of Poznań, consisting in granting the Polish population certain autonomous powers. This resulted in strong opposition from around 35% of the German population from military circles.

In April 1848, an uprising broke out, suppressed by the Prussian army. Despite the intensification of the Germanization course, it was not possible to cancel all the achievements of the revolution. Polish organizations and an independent press were established. Ultimately, however, the counter-revolution won in Germany.

Era of the Manteuffel

The so-called The Manteuffel era after the Prussian prime minister Otto Theodor von Manteuffel, characterized by the desire to liquidate the achievements of the revolution. The ideal was bureaucratic absolutism.

However, it was not possible to cancel out all the results of the revolution, such as the introduction of the constitution, the establishment of the Prussian Seym, and for some time the establishment of the all-German parliament in Frankfurt am Main. The Germanization course intensified. Polish organizations were limited or liquidated. The independent Polish press collapsed. The German language was pushed forwards in education.

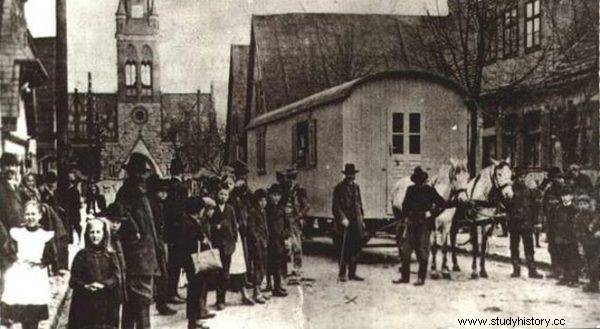

Michał Drzymała's wagon, which has become a symbol of the Polish fight against Germanization

This policy was clearly expressed by the chief president of the Poznań Province, Eugen von Puttkamer:

It is absolutely necessary for the government to take a tough and decisive position towards Polishness. Because she is and will remain his hostile element.

In the resulting situation, the only forum where the Polish question was officially raised was the Sejm tribune. The possibilities were limited, however, due to the small number of members of the Polish parliamentary circle. The strategy of the Polish Circle was to "Defend the Polish nationality in Prussian lands and Silesia", based on the provisions of the Congress of Vienna and the Prussian constitution.

The "Manteuffel Era" was characterized not only by a sharp reactionary course, but also by years of economic prosperity. The importance of the bourgeoisie and liberal tendencies living in these circles grew. In politics there was the so-called A new era associated with regent William, later king of Prussia and the emperor of Germany.

On this wave, there was a certain easing of the Germanization course. Poles took advantage of this streak. An independent Polish press was established, and in 1857 the Poznań Society of Friends of Sciences was established.

Germanization after the January Uprising

The outbreak of the January Uprising, in which Poles from the Prussian partition took part in large numbers, and its defeat was a source of repression against the participants of the uprising and the progressive Germanization of education. The tone of the policy towards Poles will be set by the Prime Minister of Prussia, appointed in 1862, and then the Chancellor of the Reich, Otto von Bismarck.

He expressed his attitude towards Poles in the famous letter to sister Malwina in 1861.

Hit the Poles so that their will to live will go away; I personally sympathize with their plight, but if we want to exist, there is nothing for us to do but exterminate them …

Otto von Bismarck.

He tried to solve the Polish issue by denationalation of Poles. The achievement of this goal would strengthen the internal unity of the Reich, and in the event of an armed conflict, it would postpone Germany from taking up the Polish issue by hostile powers.

Bismarck considered the clergy and nobility as his main opponents within Polish society. Kulturkampf breaks out with the aim of subjugating the Catholic Church. He pushed through anti-church legislation. This met with resistance from the clergy and the faithful. The repressions were very severe, including the arrest of the archbishop of Gniezno and Poznań, Mieczysław Ledóchowski. The Germanization policy in education has intensified.

The failure of Kulturkampf and a new wave of Germanization

The intertwining of two factors - the fight against the Church and the mother tongue - had a stimulating effect on large numbers of Polish society. The personal model of the Pole-Catholic was born. The Kulturkampf ended in a government failure. This spurred Bismarck to further escalate the Germanization policy.

In 1885, an ordinance of the minister of the interior, Robert von Puttkamer, was published, on the basis of which about 26,000 Poles were removed from the borders of the Hohenzollern monarchy, as well as Jews who had settled in Prussia over the decades, without the citizenship of that country. The next step was the establishment of the Colonization Commission in 1886. Its aim was to buy land from Polish hands and settle newcomers from the interior of Germany there.

Strike of the children of Września. Bas-relief in the Imperial Castle in Poznań

In the first stage, the commission had a fund of 100 million marks. The Commission started its activities in a period of deep crisis caused by the inflow of cheap overseas grain. As a result, the Commission seemed to live up to the hopes placed in it by the authorities. The commission's clients were also Polish landowners and peasants. But then the first symptoms of the crisis appeared. The lands were also sold by Prussian junkers. It was not easy to get colonists from deep inside Germany.

We will not throw the land where our family came from

Poles responded with a well-developing campaign based on parcelling companies, effectively competing with the Colonization Commission. In this situation, in 1904, an amendment to the settlement act was introduced, making the construction of a house on a newly acquired plot conditional on the consent of the authorities. This is where the case of Michał Drzymała will become famous.

The next step was the expropriation law passed in 1908, on the basis of which the authorities could expropriate large property for a pecuniary equivalent. The law sparked a wave of protests across Europe. On this wave, Maria Konopnicka writes "Rota", beginning with the words "I will not throw the land from where our family comes from". In 1912, four properties were expropriated.

Maria Konopnicka. Author of the famous Rota

At the same time, the authorities continued to remove the Polish language from education. In 1887, teaching of the Polish language in folk education was abolished. Religion was the only subject taught in the mother tongue. In 1900, a decree was issued restricting the use of the mother tongue to the lowest classes. This sparked a wave of school strikes.

The next step on this path was the Act of 1908 prohibiting the use of the mother tongue at open meetings, where the German population was over 40%. It did not include election rallies. It was referred to as the muzzle law.

Escape from the East

The Germanization policy was implemented in an atmosphere of growing nationalist sentiment. An expression of this was the establishment of the Ostmarken Verein in 1894, popularly known as Hakata from the names of its founders:Hermann Kennemann, Ferdinard von Hasemann and Heinrich von Tiedemann.

This organization fueled anti-Polish sentiment, initiated Germanization laws, including the Acts of 1897 on "the disposable fund of supreme presidents to support and strengthen the German element." Organizations were generously subsidized, but also people of merit for the state.

The current Collegium Minus was established as one of the investments aimed at encouraging Germans to settle in Poznań

A disturbing phenomenon for the authorities was the so-called Ostflucht, an escape from the East, mainly of the German population, to the Reich regions on a higher level of civilization. The flagship project was the transformation of Poznań into the capital of the German East (Hauptstadt der Ostmark):an impressive imperial forum was erected with a castle, the seat of the Royal Academy (today Collegium Minus), the Opera House, the seat of the Colonization Commission.

Balance of the Germanization Policy

The Germanization policy pursued for decades with enormous expenditure did not bring the desired results. On the contrary, it contributed to the consolidation of Poles, transforming them into a civil society with a high level of national awareness, with an extensive system of defense measures in the form of numerous economic and cultural organizations, the press, and the seeds of independence associations.

It will bear fruit when Poles take up the fight for independence in December 1918. The Greater Poland Uprising will be the only fully victorious uprising in the history of Poland.

Source:

The above text was originally published as part of a monumental work, organizing the most important phenomena and ideas functioning in Polish historical memory: Memory nodes of independent Poland . This publication was published in 2014 by the Znak Publishing House, the Polish History Museum and the Memory Knots Foundation.