Tossed on the doorstep of the church, left to be eaten by wild animals or ... drowned in the sea. Such was the fate of unwanted children in the Middle Ages.

If in the Middle Ages a woman gave birth to an unwanted child, she had few options. She could raise them with the stigma of shame, abandon them in the hope that someone would find them and take them before they fell victim to wild animals, or leave them on the doorstep of the church. The latter alternative was the most humane. Of course, as long as someone discovered the presence of a toddler before his death of hunger or cold. But even if a newborn baby died, technically it wasn't considered a murder. After all, at the time of abandonment, the child was alive and could be saved. And that fate wanted otherwise ...

Bastards without the right to life

According to medieval moral rules, largely dictated by the Church, sex was to serve the purpose of procreation. There was, however, a small "but" ... The intercourse could only take place on strictly defined (according to the liturgical calendar) days and only in the marriage bed. Relationships outside of marriage - and their fruits - were considered sinful. The consequences of this went much further than exclusion from religious life. As Rosalie Gilbert writes:

The illegitimate pregnancy was a misfortune. Such a child could not, upon reaching the age of majority, receive the inheritance due to offspring from a lawful marriage. It has not inherited. He could not count on a dowry, property, titles. It had no rights, as if it wasn't there at all , and therefore a virgin who had sex life outside of marriage was placed outside the fringes of society. Not so much because of sexual freedom itself, although it was also something terrible, but also recklessness and neglect of the appropriate legal guarantees of a possible child. Besides, she herself will not have security in her old age, which was almost unforgivable.

Out of sight, out of heart

The best solution in such a situation was a marriage (not necessarily with the perpetrator of the trouble), which would wipe out the shame and legalize the pregnancy. But in many cases, a hasty wedding was not an option. It is not so bad if, in the event of a "mishap", the child's father felt responsible and supported the mother and his bastard financially or provided them with a roof over their heads. This was not always the case, however. Gilbert cites two drastic - though unfortunately not isolated - cases of men who decided to deal with the problem once and for all:

Surfleet. The little boy was abandoned on the threshold of Thomas Leeke's home, who, according to his mother, was to be the father of her child. However, Thomas denied this and the child was taken somewhere to be mistreated and died.

Sutton in the Marsh. Sir John Wymark, a recent clergyman there, made Margaret Harburgh pregnant and gave birth. The same Sir John then threw the child into the sea and thus killed them.

Gilbert cites two drastic - though unfortunately not isolated - cases of men who decided to deal with the problem once and for all

There were many more such small, defenseless victims of the law in force and the lack of effective contraception. However, it must be remembered, however brutally it was expressed by the French historian Philippe Ariès, that "there was no childhood in medieval society" because the high mortality among newborns and infants hindered the formation of parental bonds. "People couldn't afford to get too attached to someone they were always reckoning with losing."

If you are afraid, go to God

This does not mean, of course, that children were massively neglected and abandoned (although in the light of today's knowledge about human development, some of the medieval nursing and upbringing practices raise reasonable doubts). Although such cases also happened. In the files of the court of the Archdeacon of Buckingham there are, among others, records on a certain Alice Mortyn. The woman was to give birth to a child (the father remained unknown), and then hid it in the swamps immediately after giving birth. The newborn baby died "in poor conditions."

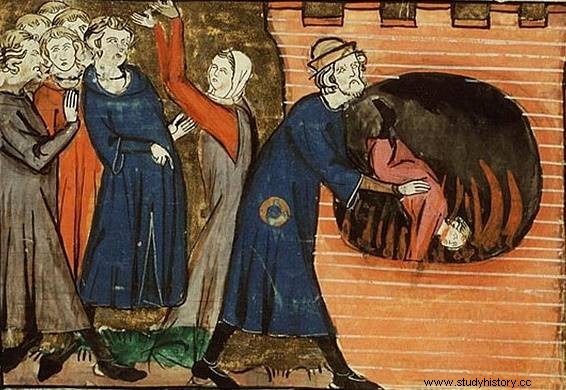

In fact, some desperate women even resorted to infanticide. In the manuscript Miracles de Notre Dame , copied in 1327 in The Hague, the story of a woman who became pregnant as a result of her uncle's promotions . Both the moment prior to conception and what happened after childbirth are depicted in color figures. The unfortunate mother was supposed to drown the newborn in the toilet. It is difficult to say whether it really happened or whether it was intended only as a parable as a warning. Eventually, archaeologists studying the contents of medieval cesspools and toilets often found human remains there.

Some desperate women even went so far as to infanticide

A humane alternative to killing an unwanted toddler was leaving him in the Church . Already in the early Middle Ages there was the practice of oblation, that is, putting a child into a monastery in order to raise him up for a future monk . Depending on the adopted rule, the Oblates could withdraw after reaching maturity (it was allowed by the rule of St. Basil) or they had no choice and had to lead a monastic life (according to the rule of St. Benedict).

Hospital of the Innocents

Over time, the oblation was criticized and gradually withdrawn from it. Mothers, however, continued to abandon their unwanted children on the doorstep of churches and monasteries. According to Joseph and Frances Gies:" The Church not only protected fetuses and newborns from abortion and abandonment, but also children from abuse by their parents. . He condemned the practice of selling children and drew the attention of the faithful to the biblical examples of the good and loving parents of young Samuel, Daniel, the Holy Youths, the little Christ. "

Interestingly, adoption - well-known and practiced incl. in ancient Rome - it happened sporadically in the Middle Ages. However, something had to be done with the foundlings. The first systemic solution to this growing problem arose in Italy. The gies write:

In the 1920s, Florence was opened by the world's first nursery for foundlings, the famous Hospital of the Innocents ( Ospedale degli innocenti ) whose architecturally revolutionary design by Brunelleschi is considered the beginning of Renaissance architecture. Like similar institutions in other countries, the hospital was a drop in the ocean of needs and the problem was exacerbated by the fact that many orphans did not have relatives to take them.

Florence Hospital of the Innocents

There was even a special window in the wall of the building where you could leave the child - it was therefore the medieval equivalent of today's windows of life . Which does not change the fact that such places were dramatically lacking for unwanted or orphaned children. Even taking into account the high percentage of infants dying due to lack of hygiene and disease, some of them lived in the first years of childhood. But even then, they could hardly speak of a grace of fate. If not in a monastery, they usually lived a sad (and short) life of underage vagrants and beggars. Medieval bastards were hardly given "happily ever after".

Bibliography:

- Philippe Ariès, Childhood Story , Aletheia 2011.

- Frances Gies, Joseph Gies, Experience love in the Middle Ages, Horizon Mark 2022.

- Frances Gies, Joseph Gies, Life of a Medieval Family, Horizon 2020 Sign.

- Rosalie Gilbert, The Secret Sex Life of Women in the Middle Ages, Rebis 2021.