How did the human crane work? Why was a caller hired? Why was it worth becoming the host of the fair? In the Middle Ages, people could earn money in all sorts of ways. Some are hard to imagine today. Or maybe only the names have changed?

In former cities, there were professions that, although typical of the world of the middle ages, may amaze modern man. Most of them no longer exist today. Which can be considered the most unusual?

Human crane (operator of a mechanical pedestrian crossing)

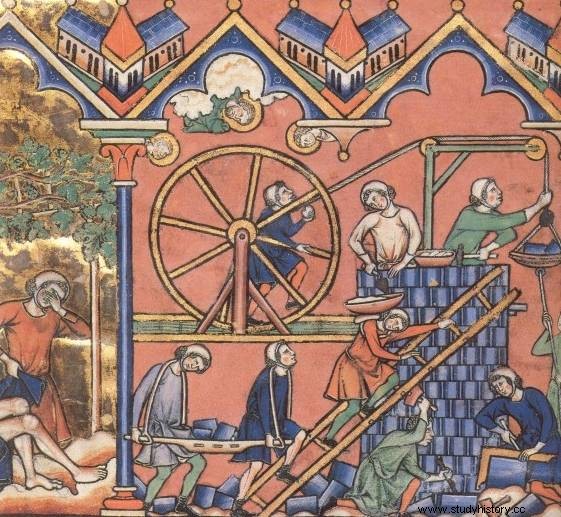

Not only is it quite unusual, it is also probably one of the most arduous of medieval activities. Without people operating first with simple cranes, and then with more and more complex machines, the development of medieval mining would be impossible.

Thanks to numerous gears and blocks in the treadmill wheel, one man was able to lift a weight of up to two tons! On the other hand, the treadmill - a conical structure, reaching several meters in height - made it possible to lift up to several tons at a time.

A 13th-century crane on a French miniature.

Work - you can imagine - had to be extremely strenuous, tiring and monotonous. Sometimes people were replaced by animals. The end of the hardships of treadmill and treadmill workers was not until the invention of the steam engine in a much later era.

Caller

What did the cringer do? It was a special messenger, extremely important to the life of the medieval city. He entered the action, for example, after the death of one of the townspeople. "His task was to announce his death and to inform about the place and time of the funeral," explain Frances and Joseph Gies, authors of the book "Life in a Medieval City" .

Clothes repairer

This profession, typical of the Middle Ages, should not be confused with the tailor, which is also popular today. This is an example of a profession that arose as a result of extremely detailed internal regulations that were introduced in craft guilds.

The fact that the profession of a tailor was known already in the Middle Ages does not surprise anyone. But why were they not allowed to repair old clothes?

Clothes repairers - as the name suggests - repaired clothes. Only and exclusively, because they were completely forbidden to sew new dresses, tunics or pants! Conversely, a medieval tailor could not repair old clothes. And since the repairers, not only of clothes, but also of furniture and clothes, were constantly on the move, in order to tweak their worn-out coat, you had to wait often until they appeared in the area.

The host of the fair

Sounds like a boring clerical profession? Wrong! Contrary to appearances, it was a very prestigious position. For example, in the French city of Troyes, "the position of [the hosts of the fair] resulted in an excellent salary of two hundred pounds (livres) a year, an out-of-pocket fund of thirty pounds, and an exemption from all fees and taxes for the rest of their lives," write Joseph and Frances Gies in "Living in a Medieval City" .

In return for these privileges, the hosts supervised the entire event with the help of an army of officials, such as seal guards or a lieutenant at the fair. There were two of them in Troyes. He chose them from among the townspeople and nobles of the local count.

Bears guide

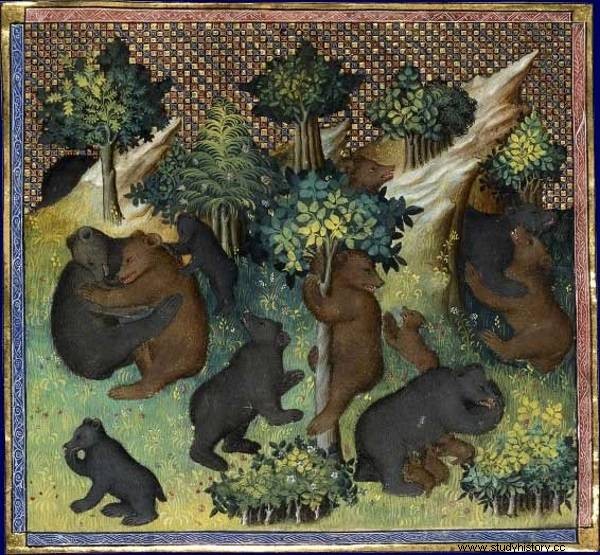

One of the less glorious pastimes of medieval people was watching animals fights. One of the scenes of this show was dogs rushing on bears captured in captivity. The latter traveled from town to town with their owners, or rather - "guides".

Bears captured in captivity traveled from town to town. They were used in fights or taught various tricks. Miniature from the 15th century.

Sometimes bears were also used to perform circus performances. As explained in the "Encyclopaedia Britannica" from 1911, such events took place at the beginning of the 20th century, and the animals were usually taken care of by ... French and Italians. Interestingly, the name of the profession (called bear-leader ) entered the colloquial language in Great Britain as ... the term for any guard or guardian accompanying someone on a journey.

Water physician (or… urine prophet)

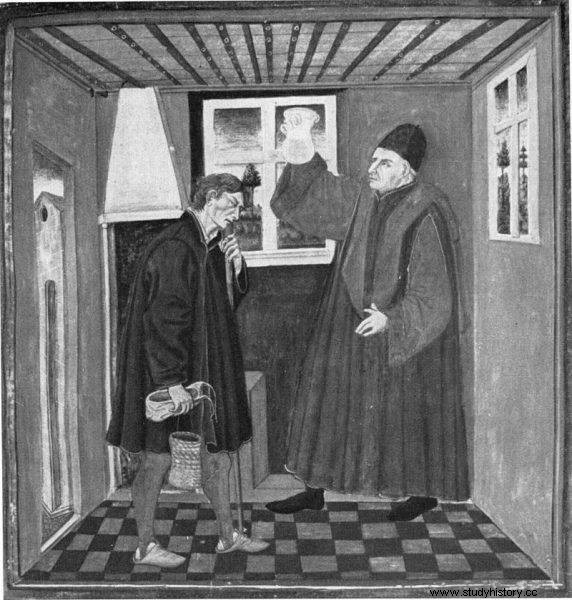

There were certainly many healers in the Middle Ages, but this kind of "medic" undoubtedly stands out from the crowd. Water doctors were concerned with determining the health of their patients solely on the basis of their urine. They studied the appearance and color of urine, its smell, and often its taste. Sometimes they proved to be really useful. Since ancient times, this urine test has been used to determine if a woman is pregnant, among other things. It was also possible to detect diabetes in this way.

It was worse when a specialist, armed only with the patient's urine, tried to use it to determine someone's character traits and prospects for the future. Back then, he probably only deserved to be called the "urine prophet."

The water doctor decided about the patient's health solely on the basis of his urine.

This profession lasted an exceptionally long time. Its representatives were mentioned, among others, by the eighteenth-century philosopher Bernard Mandeville. It also appears in the 1875 Sussex dialect dictionary. And this with the mention that at that time it was a common practice in that county to send bottles of your urine for inspection by "water doctors".

Wine maker

How did people in medieval cities know which tavern is worth going to get tasty wine? They owed it to special inspectors who also acted as promoters. This is how their profession is described by Frances and Joseph Gies:

An interesting function related to wine had a special herald, who was also an inspector:every morning this man went to the first inn that had not yet hired this type of "praiser" "And had to be employed by her. He supervised the drawing of the drink (or drew it himself) and then tasted it.

Finally, equipped with a cup and a leather bladder stuffed with a piece of hemp, he went out to advertise his wine and offer free samples to passersby. In order to keep prices under control, he would also ask the inn's customers how much they had to pay before departing.

Bibliography:

- Joseph Gies, Frances Gies, Life in a Medieval City , Horizon 2018 sign.

- The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Global Medieval Life and Culture, Joyce E. Salisbury, Greenwood Press 2008.

- Walking circle and Kierat , website of the Medieval Mining Village.

- Bernard Mandeville, A Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases , edited by Sylvie Kleiman-Lafon, Springer 2017.

- William Douglas Parish, A dictionary of the Sussex dialect and collection of provincialisms in use in the county of Sussex, Oxford University 1875.

- Henryk Samsonowicz, The Life of a Medieval Town , PWN 1970.