Although neither Jane Austen nor her sister Cassandra never stood in front of the altar, they both knew very well what the fate of a married woman at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries was related to. And maybe it was this knowledge that made Austen prefer to end her novels with the illusory “they lived happily ever after”?

In December 1815, John Murrey's publishing house published "Emma". Jane Austen's fourth novel and the last to be published during her lifetime. At first glance, it was another, light story about the adventures of young ladies, all of whose activities came down to finding the right man and dragging him to the wedding carpet. It was a standard ending, in the opinion of many people it was due to Jane's old age. After all, what could she know about married life?

Merry Old England?

The work of one of the most famous English writers fell on the Georgian era, which in Great Britain is defined as the reign of five Hanoverian kings:George I, George II, George III, George IV and William IV. It was a moment of great changes, both cultural and social, political and economic.

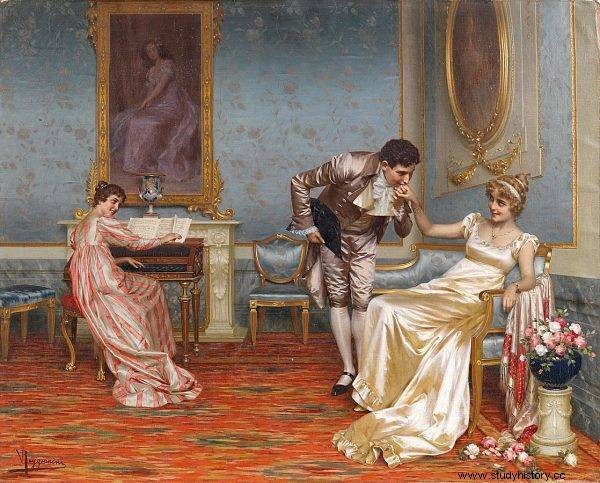

It is also the heyday of the so-called "Merry Old England", or England "stagecoaches, vast, yet unfenced green pastures and lush hedges full of birds" . This idyllic landscape, inhabited by gentlemen, caricatured ministers and ladies spending their days playing the clavichord, painting and searching for husbands, is familiar to readers from the pages of Austen's novel.

This idyllic landscape, inhabited by gentlemen, caricatured ministers and ladies spending their days playing the clavichord, painting and searching for husbands, is familiar to readers from the pages of Austen's novel.

However, this idyllic picture hid beneath its surface a sad truth about the position and fate of women, which Jane intelligently smuggled into her books. And it was a bitter story with no happy ending.

Read also:The great writer founded &# 8230; own religious movement and was excommunicated for it. What was Tolstoism?

The age of pregnant women

Only widows could enjoy a certain degree of independence in those days in England. In the light of the law of the time, British women did not inherit their landed estates, which made them dependent on someone else's dependence. First, the father, then the husband, and when they were unmarried - the brother. Unfortunately, the mere marriage, even if it was happy, did not guarantee them long life.

The physiological side of women's lives is not reflected in the literature of those times, but is often referred to in the correspondence of women. The gentle references to the relief with which the menopause is received, the dreaded remarks in Jane's letters to Cassandra about the news of her family's subsequent pregnancies, and finally the formidable list of women giving birth each year, which we find out by browsing through family correspondence - it all adds up to the frightening picture of married women in Jane Austen's time.

It was the fate of all married women, regardless of their social status and wealth. As long as they were able to get pregnant, in most cases they spent most of their marital time there, as was the case of Queen Sophia Charlotta. During her marriage to Jerzy III, she gave birth to fifteen children. And it can be said that she was one of the happier women as she did not die in childbirth.

Queen Zofia Charlotta gave birth to ... 15 children!

Read also:Even 150 people assisted in childbirth at European courts. Public births were the norm in the modern era

Right to life

Multiple pregnancies and difficult births affected women both physically and mentally. The Age of Enlightenment began with changes that began to be manifested by the improvement of living conditions and the development of medicine, including the knowledge of birth control. Unfortunately, the death rate of women in childbirth was still appalling. Which Jane Austen knew very well, as most of her sisters-in-law died in puerperium, including two after giving birth to their eleventh child.

A married woman was “demanded of continual submission,” which for many of them eventually became the nail in the coffin. As the acting judge Sir William Blackstone wrote: "in marriage the husband and wife are one person - that is, the very existence or legal existence of the woman is suspended for the duration of the marriage" . In other words, the only person with rights in the relationship was the husband. And his unquestionable right was to enjoy the pleasures of the marriage bed.

The end of the 18th century brought the first protests against such treatment. Among the pioneers who spoke out loud about gender inequalities and the lack of women's rights, there were, among others, Mary Wollstonecraft or the French suffragist Olimpia de Gouges. Unfortunately, their voices were isolated cases, disregarded in a world ruled by the male part of the population.

Jane Austen, the only existing portrait of the writer, by her sister Cassandra

However, the issue of sexual abstinence was a topic that caught the attention of men. Unfortunately, not because of concern for women's health, but because of fear of excessive population growth. One of the representatives of such thoughts was Pastor Thomas Robert Malthus, who “looked at the problem of having many children from the point of view of an enumerator. He believed that his country would not be able to feed such a rapidly growing population. ”

Unfortunately, he was in the minority which time has shown to be right. The next era brought many crises and excessive population growth played a key role in them. It is worth mentioning that during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901), about 15 million people emigrated from Great Britain as a result of these events.

Read also:Strong women in the family, or who ruled the country in the Saxon times?