Disregard by officials, violence at police stations - this is everyday peasant life in interwar Poland.

The peasant Stanisław Kusek from the village of Borowa in the Ropczyce district was unlucky. As he was walking down the road, he was picked up by a patrol by the State Police. At the station "30 policemen standing in a double row" he was beating him with clubs. For nothing. Then Kusk was released as if nothing had happened. The detention had no cause. It was 1933.

The police treated Józef Worka in a similar way - at the police station he was beaten for several hours. They were scared by shooting. Many similar accounts are known. The peasants were humiliated because they were seen as oppositionists, communists or descendants of Jakub Szela - the leader of the Galician uprising.

According to the message of the peasant Walenty Szeliga, the policemen shouted at him - "You are a bandit! She's damn damned ” . Another peasant, when he was picking up the strings, shouted:"People, be afraid of God, how can you beat someone like this?", He heard from the constable: "I am your God" .

As historians Piotr Cichoracki, Joanna Dufrat and Janusz Mierzwa write:"the violence used by PP officers in the investigations was an integral part of its activities."

Police violence was related to peasant riots, which, especially during the crisis, grew stronger. But nothing justifies her. Nevertheless, as historians Piotr Cichoracki, Joanna Dufrat and Janusz Mierzwa write:"the violence used by PP officers in the investigations was an integral part of its activities."

The Second Polish Republic did not fulfill its promises made to peasants at the dawn of independence. Back then, when borders had to be defended, peasants and workers were promised reforms - including land reform. Then it was forgotten and the reform actually turned out to be a fiction.

Other reforms, such as the labor law reforms, looked good on paper, but in practice it was much worse. The authorities preferred to deal with the great landowners and entrepreneurs - mostly conservative circles. Peasants were identified with voters of opposition popular groups or with radicals. However, not all peasant rebellions were politically motivated - many of them resulted from poverty, feelings of hopelessness and despair, and from fear of further administrative burdens.

Not sausage for a dog, not for a cinema farmer

The countryside was harassed in various ways. Most often, the persecution was of a financial form. The authors of the work on social rebellions in the Second Polish Republic write:

The real bane of the rural population, regardless of ethnicity, was administrative penalties arbitrarily imposed by PP officials and officers.

You could be punished for almost everything - for not keeping the dog tethered, dirty yard, not covering the well, drying clothes on the fence, transporting pigs incorrectly to the market or the insulting treatment of a policeman. Of course, the penalties were imposed on a discretionary basis and it was virtually impossible to appeal against them effectively.

"You are for the master, not the master for you" - one peasant recalled the attitude of a forester in the Radomsko district. So the peasants had to wait for hours until the ranger would wake up or finish drinking his tea and kindly collect the litter.

He heard him departing:"not sausage for the dog, not cinema for the peasant."

Another peasant in the Lviv voivodship wanted to open a cinema - he collected the necessary money for a projector, but the starosty did not give him a license under any pretext. He heard him walking away: "not a sausage for a dog, not a cinema for a peasant" .

Adam Leszczyński, who describes these stories, has no doubts that the peasant in contemporary Poland could feel a second-class citizen. He should pay taxes and expect nothing in return. When he did not pay - the tax administration entered with all force. When he rebelled, he was punished ruthlessly. The list of torture at the police stations was long:stabbing splinters by nails, tearing hair, beating feet with rubbers and pouring water upside down into the nose and the like.

Most interventions (including parliamentary interventions) on violence have ended in nothing. The allegations were found to be unfounded.

The return of serfdom?

The Great Depression was the catalyst for rural revolts, but many of their causes lay deep in the past. The peasants remembered serfdom and other wrongs. In 1937 Maria Dąbrowska wrote:

When the landed gentry thinks that concealing the fact of past harm and social inequality is sufficient to maintain social harmony and love, it is a mistake to do so. Social hatred has been sown and cultivated for centuries by the owned and privileged classes.

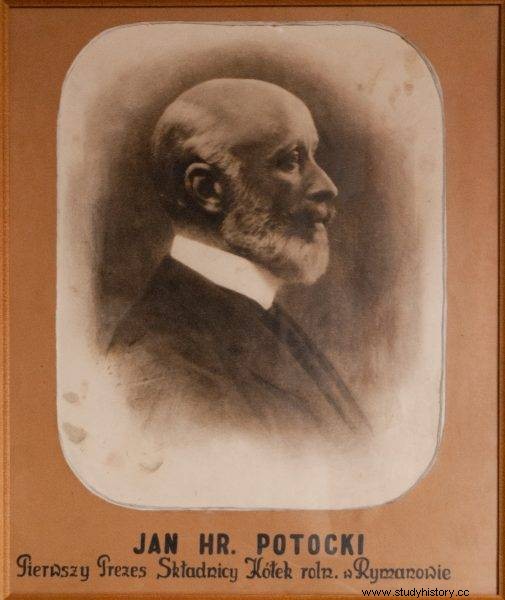

Count Jan Potocki, the owner of the Rymanów estate, showed no sense of social mood. In June 1932, he came up with the idea that the local population should repair roads and bridges in a community effort. The idea may be good, but the local peasants associated it with serfdom, the return of which was feared. After all, they wanted to engage the villagers to work for free, while the care for roads and bridges belonged to the local administration, also supported by their taxes.

Count Jan Potocki, the owner of the Rymanów estate, showed no sense of social mood.

There were riots, and soon fights - numerous reinforcements in the form of several hundred policemen were brought in. Shots were fired, wounded on both sides. Several participants of the incidents were killed.

In turn, when in 1937 there was a peasant strike (mainly in Galicia), the state reacted brutally. Dozens of people died, several thousand people were detained. Additionally, peasant homes were demolished and plundered. Of course, there were voices that this attitude of state representatives discouraged peasants from it and was a great opportunity for communists or - in the case of Eastern Galicia - Ukrainian nationalists.

One of the documents of the Nowogródek Voivodship Office stated directly that each beaten was a new enemy for the state. "Nothing more than this is conducive to the development of the anti-state movement" - stated the conclusion during the meeting of starosts in the voivodeship. So it happened that police brutality was punished - but these were exceptions to the rule.

In 1936, Maria Milkiewiczowa, paying attention to the general poverty and backwardness of the countryside, warned in "Wiadomości Literackie":"For those for whom schools are not built, prisons will be built.

Bibliography:

- Piotr Cichoracki, Joanna Dufrat, Janusz Mierzwa, Faces of social rebellion in the Second Polish Republic during the Great Depression (1930-1935). Conditions, scale, consequences , Krakow 2019.

- Adam Leszczyński, People's history of Poland , Warsaw 2020.

- Czesław Miłosz, The 20th Anniversary Expedition , Krakow 1999.